Seagrass meadows: an underwater time capsule for archaeology

…by providing a protective matt above exceptional archaeological treasures.

The most beautiful meadows are to be found along the world’s sandy coasts: Seagrass.

It lines the seafloor like an enormous carpet. In the Nordics, shallow coastal waters are dominated by the seagrass "eelgrass" (Zostera marina).

Seagrass has some important functions, such as removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and protecting our coasts from sea level rise, and boosting biodiversity.

But seagrass can do even more than that. An international research project has now documented how seagrass also protects our cultural history.

Our results are published in the journal, Ambio.

How seagrass protects archaeology

Numerous archaeological treasures lay just a stone’s throw from the coast: Stone Age settlements in Denmark, Phoenician, Roman and Greek shipwrecks with their cargo in the Mediterranean Sea, and more recent wrecks in Australia.

Underwater meadows stabilise the seafloor by dampening wave energy and forming a stabilising network of roots and stems.

They also build up the seabed by capturing remains of seaweed and other particles in mat-like layers, burying deeper sediments and protecting anything buried within them as the seagrass continues to grow.

And they help to provide the right conditions needed to preserve archaeological treasures by locking out oxygen, which might otherwise promote degradation.

And so, the organic and chemical structure of seagrass meadows creates a type of underwater time capsule that can encase and protect shipwrecks or Stone Age settlements, for thousands of years.

Read More: Archaeologists reveal new finds from legendary Swedish warship

Treasures lurking in Danish seagrass meadows

In Europe, many settlements were inundated by rising seas during the Holocene – the geological epoch that began after the end of the last ice age, 11,700 years ago, and was characterised by rising sea levels after the ice melted.

With time, these sites became covered in sediments and colonised by seagrass.

Diver investigates remains of a wattle mat from the younger Stone Age preserved under seagrass at Nekselø, Denmark. (Photo: National Museum of Denmark)

Under these meadows today, lay a number of exceptional finds. For example, near the Danish island of Nekselø, you can find a well preserved wooden fish traps from the early Stone Age. And off the Fyn coast, there are remnants of wood, pottery, and animal bones, along with intact burials from the late Stone Age.

All of these are preserved to this day, thanks to seagrass.

These archaeological sites provide a unique insight into the life and cultural conditions of the past. And there are many other similar sites in the Danish coastal areas and around the world.

Read More: How Nordic marine forests can help fight climate change

Seagrass as a historic archive

The gradual build-up of the seabed over the millennia provides insights into human activities throughout history. We can also use seagrass as a type of archive that we can dig in to and study the past.

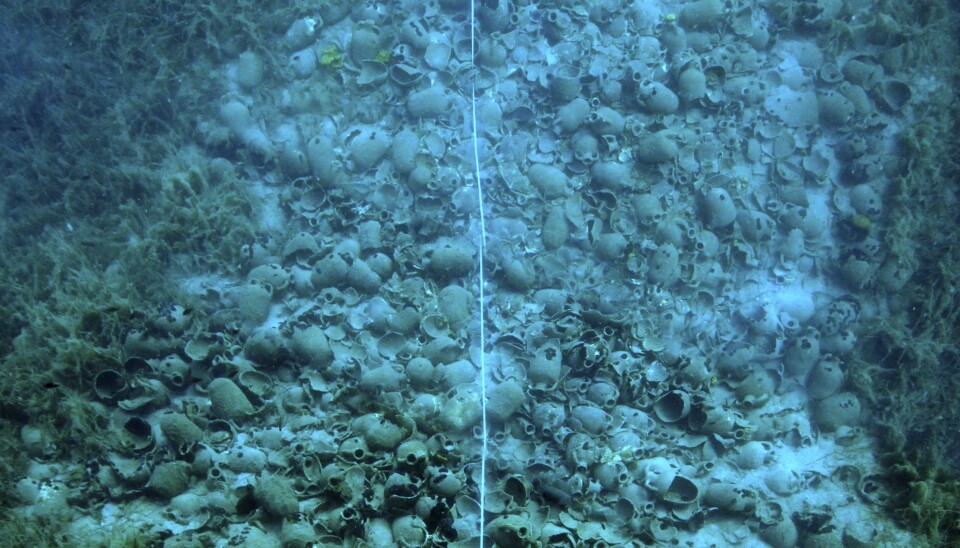

Dates and chemical analyses of the thick deposits underneath seagrass in the Mediterranean (Posidonia oceanica, see the second photo in the gallery at the top of this article), give us a glimpse of how soil was used in agriculture and metal extraction.

Analyses of more recent deposits reveal a drop in lead content, associated with the transition to unleaded fuel.

Read More: Greenland seaweed helps combat ocean acidification

We should protect seagrass while we still can

But seagrass is not invincible. It is sensitive to poor water quality, physical damage, and heat waves.

In our study, we document how the loss of seagrass has exposed archaeological sites, including shipwrecks, axe handles, animal bones, and more, representing a loss of cultural history.

Seagrass retains carbon in the seabed, thus counteracting global warming, it protects the coasts by damping the wave energy, and promotes biodiversity in our coastal areas.

And so, marine archaeologists and marine biologists are in a race against time to protect vulnerable meadows.

In the last few years, the ability of marine forests like seagrass meadows to dampen and adapt to climate change has led to the development of Blue Carbon strategies – the offsetting of carbon emissions by protection and expansion of marine forests.

I hope that their other role as a protector of archaeology and cultural heritage will further boost efforts to preserve and protect these underwater meadows.

After all, this underwater resource is worth protecting.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk