Ancient Palmyra: A story of urban resilience

The warrior queen of Palmyra, Zenobia, made a stand against the encroaching Roman Empire, but was ultimately defeated. But what happened next, after the Romans left is less documented. A new book reveals how Palmyra survived in Late Antiquity.

Zenobia was a famous warrior queen who dared to challenge the Roman Emperor and crippled the empire with an ambitious military expansion.

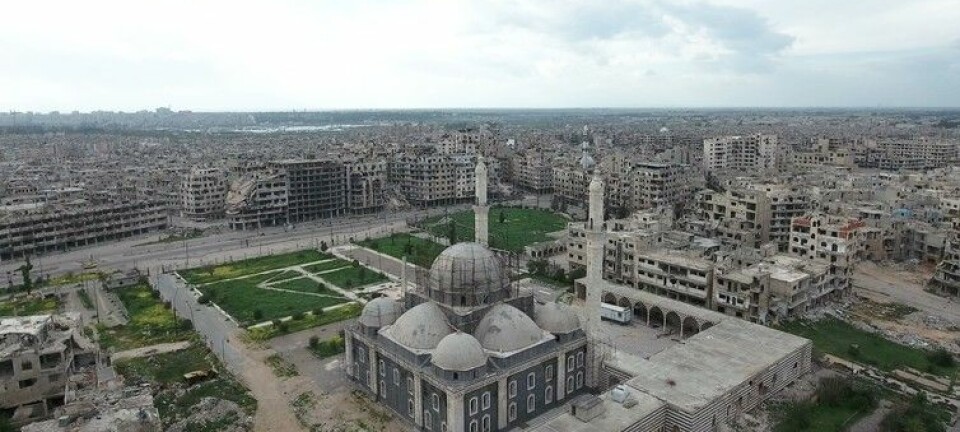

She lived in Palmyra in the late 3rd century AD, in what is today Syria. The remarkably well preserved remains of Palmyra have recently undergone major destruction due to the current conflict, but the site remains one of the best-known urban settlements in the Roman East.

According to ancient written sources, Zenobia’s dreams of glory for Palmyra were shattered by a successful Roman counter-campaign that culminated in the destruction of the city, ordered by Emperor Aurelian (270-275 CE) in 272/273 CE.

But to what extent can we trust written sources? What really happened to Palmyra next, in the time after Zenobia? A research project initiated in 2011 has been trying to answer this very question.

Our results are now published in a new book “Palmyra after Zenobia (AD 273-750) – an archaeological and historical reappraisal”.

272/273 CE – Palmyra’s urban watershed

Based on a reassessment of published reports and unpublished archival data from past archaeological excavations and surveys, along with a large corpus of Latin, ancient Greek, Syrian, and Arabic written sources, the project has so far managed to shed new light on the fate of Palmyra.

It appears that the events of 272/273 CE marked an important watershed for the history of the city. The settlement’s inhabited surface area shrank to almost half of its original size and major projects ended abruptly, such as the construction of a majestic 1.2 kilometre-long street named by scholars after its porticoes, the Great Colonnade.

From the 4th century CE, the rich houses of the urban aristocracy stopped being lavishly adorned, suggesting an exodus of the aristocratic elite.

Read More: Researchers expect continued destruction in Palmyra

A new beginning

Nonetheless, the city was not completely abandoned and was gradually rebuilt from its ashes, demonstrating remarkable urban resilience, as we would say today.

Palmyra in Late Antiquity, however, would have looked very different from that of the Roman period.

From the late 3rd century CE, construction of new buildings, public and private, was underway, using reused architectural material.

Public streets and squares were gradually devoured by the advance of private space, meaning houses and shops. This, in itself, does not necessarily point to urban decline, rather to the existence of a thriving urban community that was struggling to find space to live within the city walls.

Read More: High definition archaeology reveals secrets of the earliest cities

A changing townscape

One of the main reasons behind the survival of Palmyra must be related to the installation of a garrison in the city, the Legio I Illyricorum, in a newly built fortress, which eventually became the economic engine of the settlement.

The advent of Christianity was also an important agent in transforming the city. Palmyra had a bishop from at least the early 4th century and, from the end of the same century, urban pagan sanctuaries were gradually abandoned or converted into churches, as with the famous Temple of Bel.

At least eight churches have been found in Palmyra: Church 4 being one of the largest in the entire early Christian Syria, excavated by a Syro-Polish archaeological team.

When in 634 CE the Muslim force of the caliph Abu Bakr guided by the general Khalid ibn al-Walid, the “sword of Allah,” reached Palmyra. The city surrendered without a fight.

Read More: Archaeologists: Cities deserve better treatment

Palmyra after the Islamic conquest

Palmyra in the early Islamic period (634-750 CE) shows incredible continuity from Late Antiquity, but major changes are also visible in the urban layout. Perhaps one of the most remarkable changes is the addition of a congregational mosque, which was installed in an existing building close to the ancient Roman theatre.

A suq, an open bazaar, was also installed in the carriage way of the central section of the Great Colonnade, suggesting the commercial vitality of the settlement even in this period.

The fortress which had once garrisoned the Roman legion was no longer needed as Palmyra was no longer situated along a frontier, but was now at the centre of the growing territory controlled by the Islamic caliphate in Damascus.

Read More: Ancient Roman artifact found on Danish island

The end of the ancient site

Eventually, political stresses put an end to Palmyra. In the early Islamic period, the city housed the powerful tribe of the Banu Kalb, who supported the Umayyads, the ruling dynasty in Damascus.

When the Umayyads were replaced by the Abbasids in 750 CE, the political agent behind Palmyra´s survival ended abruptly.

The city gradually shrank in size and, by the 10th century CE, it became entrenched into the precinct of the Sanctuary of Bel. The glorious history of the settlement was at an end.

Read More: Once lost archaeology revealed by satellite images and aerial photography

New milestones and future directions

The publication of the new book is an important milestone, but there is still much to be done to unravel the mysteries of Palmyra after Zenobia.

The project, now based at the Centre for Urban Network evolutions (UbNet), at Aarhus University, Denmark, continues to gather new important data to cast light on this neglected phase of Palmyra´s history, including old documentation of past archaeological excavations and surveys.

It is also attempting to place Palmyra´s late antique and early Islamic history into a much wider regional and empire-wide context by understanding to what extent the urban evolution of the site represents trends in contemporary settlements.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

This article was updated on 8. August to clarify where the project is now based, at the Centre for Urban Network Evolution (UrbNet) at Aarhus University, Denmark.

Scientific links

- Centre for Urban Network Evolutions

- “Palmyra after Zenobia (AD 273-750) – an archaeological and historical reappraisal”.