The Black Death has been hiding among us for thousands of years

Fossil DNA reveals that the plague is much older than previously suspected. The discovery could shed new light on the evolution of a deadly disease.

One of history's deadliest killers has been on the rampage for longer than anyone previously suspected. This is the conclusion of a new study, which found a strain of plague bacteria in skeletons as old as 5,000 years in Europe and Asia.

"Plague is a much older phenomenon than we thought, and was widespread in Europe and Asia even before the establishment of cities," says Professor Eske Willerslev of the Centre for GeoGenetics at the Natural History Museum, Denmark, who spearheaded the research.

In the study, scientists have tracked the development of the plague bacterium from 5,000 years ago until the grisly killings of the Black Death, which ploughed through Europe and destroyed up to half of the population in the 14th century.

"It's a fascinating article," says Professor Hendrik Poinar at McMaster University in Canada, who in 2014 set the previous record of ancient DNA plague bacteria, from a 1,500 year-old skeleton.

"From an evolutionary point of view, the study rather beautifully shows us how fossil DNA can give a timing for the acquisition of key infection factors. And in this way, the article is a real 'slam dunk'," says Poinar.

The study has just been published in the scientific journal Cell.

Bronze Age skeletons had plague

It all started in January 2015, when scientists gathered to discuss the results of another, earlier study.

They had sequenced the genome of 101 skeletons from the Bronze Age (from 3,000 to 5,000 years ago) to see who lived where, how they were related, and how they are related to us today.

The genomes struck upon a landmark discovery: Approximately 5,000 years ago, there was a huge turnover of genes in Northern Europe.

"We see that the main part of modern European DNA originates from around this time,” said Willerslev then.

The research showed that the existing farming peoples of Europe were completely replaced within just 100 to 200 years, by a nomadic people--the Yamnaya, who migrated thousands of kilometres from the Caucasus in the east.

It raised a huge question: how could they suddenly push the existing agriculturalists out of the way? Were they mighty warriors? Did they have superior technology? Or did some calamity wipe out the local culture, paving the way for invasion by the Yamnaya?

"We sat down and discussed it, and I said that there must have been a huge epidemic," says co-author Kristian Kristiansen from Gothenburg University, Norway. Thoughts quickly turned to the Black Death.

Plague found in seven individuals from Siberia to Armenia

Initially, the scientists did not take any new samples, but went back to all of the pieces of DNA that were discarded as microbial contamination during the previous large study on DNA, and found small pieces of DNA that matched that of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis.

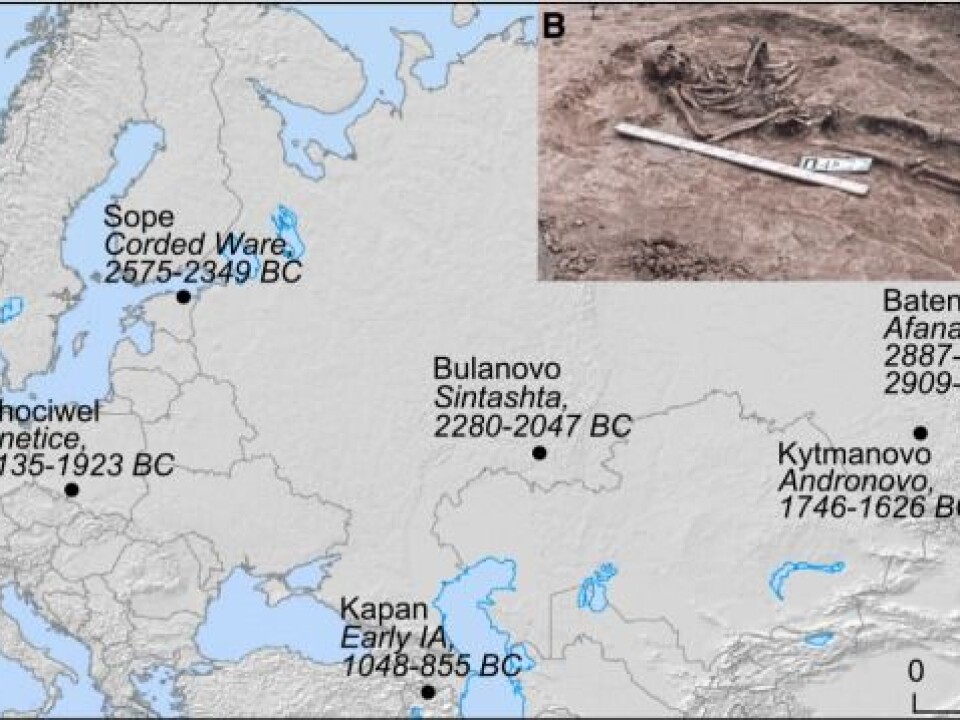

Then they went back to the original samples of human teeth and looked into the bacterial DNA in even more detail and found old strains of the plague in seven individuals spanning Eurasia—including a 5,000-year-old individuals in Siberia, a 4,000-year old skeleton in Poland, and a 3,000-year-old Iron Age individual from Armenia.

Archaeological studies at these sites showed that there was a sudden decrease in the populations around one hundred years before the Yamnayan expansion.

"My suggested scenario is that the earliest contact with the nomadic tribes occurred in Eastern Europe, and that the plague spread in these Neolithic populations," says Kristiansen.

Plague creates huge community upheaval

If Kristiansen is right, the new research gives scientists an insight into one of the major driving forces of our own history: diseases.

According to him, the deadly rampage of these plague bacteria in the Bronze Age had far-reaching consequences for European culture, by clearing many of the existing people out of the way and making room for a new culture to take over.

"We know that the whole culture changed at this time, and whereas before it was about the collective, the central focus now becomes much more about the individual and small families," says Kristiansen.

"Their culture is the foundation for everything that comes later—it goes well beyond the Bronze Age," he says.

The plague evolved from harmless soil bacterium

The new study provides a window into the development of plague bacteria--from harmless soil bacteria to a deadly killer.

The scientists saw that the bacterium began to develop an ability to hide under the immune system's radar--using a protein that normally acts as a red flag to the immune system.

The protein called flagellin, acts as a tail that helps the bacteria to propel itself and move around. This 'motor' is only found in the two oldest skeletons, dated around 5,000 years ago. But losing this ‘motor’ appears to have been an evolutionary advantage for the plague bacterium.

Later on, several minor adjustments between 3,000 and 3,700 years ago allowed the bacterium to develop a new gene called YMT (Yersinia murine toxin).

This gene allowed the plague bacterium to survive in flea intestines, and was crucial in allowing fast transmission of the bacteria to new hosts--animals and humans via fleabites.

"I think this story is very plausible," says Mikkel Heide Schierup from the Centre for Bioinformatics (BiRC) at Aarhus University, Denmark.

"But it’s of course just a few samples, so the chain of events they describe is speculation, albeit plausible speculation. With more samples we’ll be able to see exactly how correct it is, or if we’ll need to refine it," he says.

-----------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex