Oceans drive climate change

Researchers say that changes in the climate can be traced in the ocean hundreds of years before there is any trace of it in the atmosphere.

Oceans are better at predicting changes in the climate than previously thought.

At least if you believe the latest study from an international research group led by scientists from Aarhus University and the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS).

“Up until now it’s been assumed that the atmosphere reacts faster than the oceans when changes in the climate occur,” says Professor Marit-Solveig Seidenkrantz, of the Institute of Geoscience at Aarhus University, who co-authored the study.

“But our results reveal that the ocean changes hundreds of years before the same changes can be measured in the atmosphere and this indicates that the ocean is considerably more sensitive to climate change than we’ve believed so far,” she says.

Deep ocean samples unearth 3,000 years of climate change

The researchers were particularly interested in the period between 11,000 and 12,000 years ago when the transition between the last glacial period and the current Ice Age occurred.

To investigate this time period, the scientists have been trawling up and down the Canadian east coast, drilling for soil samples and collecting fossil algae from the ocean floor.

This is where they collected a five-metre long core sample taken from a depth of 239 metres in the waters off the coast of Newfoundland.

“3,000 years of climate history is stored in this core,” says Christof Pearce, a PhD student from Aarhus University and first author of the study recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

Up until now it’s been assumed that the atmosphere reacts faster than the oceans when changes in the climate occur. But our results reveal that the ocean changes hundreds of years before the same changes can be measured in the atmosphere and this indicates that the ocean is considerably more sensitive to climate change than we’ve believed so far.

“Every centimetre represents a period of about six years, so taking a sample every centimetre allows you to reconstruct the climate history in very, very great detail,” says Pearce.

Fossil algae keep memory of water

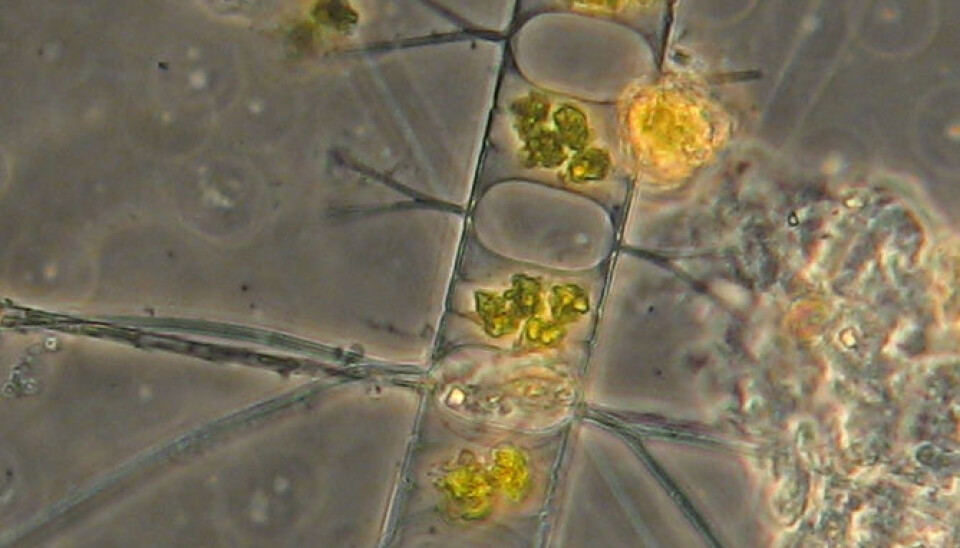

Through carbon-14 dating, geochemical and paleontological tests the researchers reconstructed the 3,000-year climate history by looking at something as innocent as fossil algae contained in the core sample.

”In just one gram of sediment there could be millions of fossil algae and each single one of them has a little story to tell about where they lived and what kind of climate they lived in,” says Pearce.

The fossils contained two different species of the family of diatoms, one of the most common types of phytoplankton, and these two different species were of particular interest to the scientists.

They only live in either cold or warm waters and combined with the carbon-14 dating this knowledge allowed the scientists to read out ocean temperature developments with great precision towards the end of the latest Ice Age.

Changes in oceans change the atmosphere

Another property of diatoms is that they create a special organic bond when there is sea ice in the water and looking for the abundance of this bond in the algae, the scientists could follow the retreat of the sea ice in the transition between latest and current Ice Age.

“One of the things we can see is that the amount of cold water was greater during the latest Ice Age,” says Seidenkrantz. “But then the cold waters fainted, the Gulf stream grew in force and this made the sea ice disappear very fast.”

Over a period of only50 years towards the end of the latest Ice Age, temperatures rose with ten degrees Celsius and the onset of this massive change in climate appears in the core sample many hundreds of years before the same change can be read from samples off Greenland’s ice sheet preserving atmospheric history.

The oceans changed before the atmosphere and therefore the scientists from Aarhus think they have a strong indicator that the oceans drive climate change – at least before the atmosphere does.

Climate scientists learn from time

The transition between latest Ice Age and the current Ice Age is the biggest climate event in newer times and that makes it an important for climate scientists to look at this period if they want to understand what drives these major changes.

It is only during the last 150 years that we have begun registering temperature changes and the amount of sea ice did not become traceable before the satellite launches in the 1970s.

“If we want to understand the history of the climate we have to look at the Earth’s history. Only through that we can learn what causes these changes, says Seidenkrantz.

Knowledge of ocean currents can model the climate

She thinks the new results make it necessary to rewrite current climate models used to predict the weather system’s behaviour.

“From now on we should consider looking more at what happens in the oceans because changes in the oceans have a deep impact on the general climate,” she says.

But it will take time, she says, because climate models are huge and complicated, so changing them is not something you just do.

Meanwhile, she and the rest of the Aarhus climate scientists will continue their research and gather more knowledge of oceanic climate.

“By looking at how the weather system has behaved we’ll improve our ability to understand all the connections and use them to predict what happens in the future,” says Seidenkrantz. “We’ll be better at explaining why draughts happen in some places while other places are flooded, because everything is connected through the climate system.”

All quiet on the ocean front

Elsewhere in Denmark the results from Aarhus do not stir great excitement:

“There is nothing new in climate change being able to be measured in the oceans before they can be measured in the atmosphere,” says professor Eigil Kaas, of the Institute of Climate and Geophysics at the Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen University. Kaas is not associated with the research project but has read the study.

“Climate models were never built on the thesis that climate variations appeared in the atmosphere first,” he says.

He believes the ocean processes described by the Aarhus scientists are already part of the modern climate models but he does acknowledge the importance of their findings. With the new results they will be able to make the models more precise, he says.

“If the condition of the oceans is well-known then it will give a certain predictability about how the climate will change in the next decade or so,” says Kaas, but adds that the study’s results are not directly translatable to our modern climate.

“What happened in the Younger Dryas (the end of the latest Ice Age) occurred during a different climate and completely different conditions so that development cannot be used as a direct analogue to global warming," says Kaas.

Yesterday’s weather predicts tomorrow’s

Christof Pearce from Aarhus University agrees that their results cannot be used to describe current climate changes.

“We studied the sudden rise in temperature between Ice Age and non-Ice Age and that is not something we expect to happen again anytime soon.”

But he thinks their results are important for the improvement and development of better climate models. By using their findings from Newfoundland, theoretical climate scientists like Eigil Kaas have something to test their calculations against.

If the model fits the past then there is a good chance it will also fit the future, says Pearce.

“All these small studies are merely parts of the larger puzzle that is to understand the mechanics behind climate change.”

They may have turned over one piece by proving that climate change occurs in the oceans hundreds of years before the atmosphere follows suit but there is still many questions unanswered.

“Who knows what drives the changes in the oceans?” he asks.

---------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Kristian Secher