Ancient sculptures were full of colour

The ancient Greek and Roman sculptures were not just white. They were filled with colour, and a new research project aims to restore these lost colours.

Most people have an image of what sculptures from ancient Greece look like. They’re marble white, and they probably lack legs and arms.

But the sculptures haven’t always looked like that. They were once full of colour, but after centuries in the soil, their original appearance and their colours have vanished.

Since 2009, researchers at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek museum in Copenhagen have been working on a research aiming to bring these lost colours back to life.

If we can learn more about the colours, we can learn more about the sculptures themselves, says archaeologist Jan Stubbe Østergaard.

”The colours are an integral part of the sculpture, and you cannot fully understand a sculpture until you’ve seen it with its original colours,” he says.

An example of the importance of colour can be seen in the Roman toga: togas had different colours, each of which indicated a certain social status. If the sculpture has lost its colour, not much is known about the social status of the carved person.

Experts have known about these colours for a long time, but it’s not something the general public knows a lot about. And when the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek museum had its first coloured exhibition in 2004, it caused quite a stir.

The colour brings us closer to other cultures

The apparent fact that the ancient sculptures were actually coloured may be of great importance to the European sense of self. According to Østergaard, all other high civilisations painted their sculptures, so the white marble has stood out from the rest of the world.

”European high culture was not characterised by respect for other cultures, and the Greeks even described Persians as barbarians,” he says.

“In our own imagination, we Europeans have regarded ourselves as different and superior throughout history. The Europeans have regarded the white marble figures as the ideal for sculptures because they were different from all the others.”

An example of the elevated position of white marble can be seen in a building like The United States Capitol in Washington, US. With its white marble pillars, it not only looks like it’s antique, it also shares its name with one of the seven hills of Rome.

“This is just one of many examples of the importance that white marble has had on European identity on many levels.”

When the colour disappeared

Only a few experts knew about these colours. Today, however, we have a different approach to knowledge. Today we’re trying to restore the colours and include them in the history books.”

But how come we’re only hearing now that the sculptures were painted?

Many of the colours have vanished as a result of natural degradation processes. Moreover, up until the 1930s, it was common practice to clean archaeological finds, sometimes even with steel brushes.

”It can be very difficult to see whether a sculpture has been painted when you dig it up. Add to that the general view among archaeologists that their finds should always be cleaned up.”

During the 1800s, it became increasingly clear to archaeologists and other experts that the sculptures used to be coloured.

”Only a few experts knew about these colours. Today, however, we have a different approach to knowledge. Today we’re trying to restore the colours and include them in the history books.”

The return of the painted sculptures

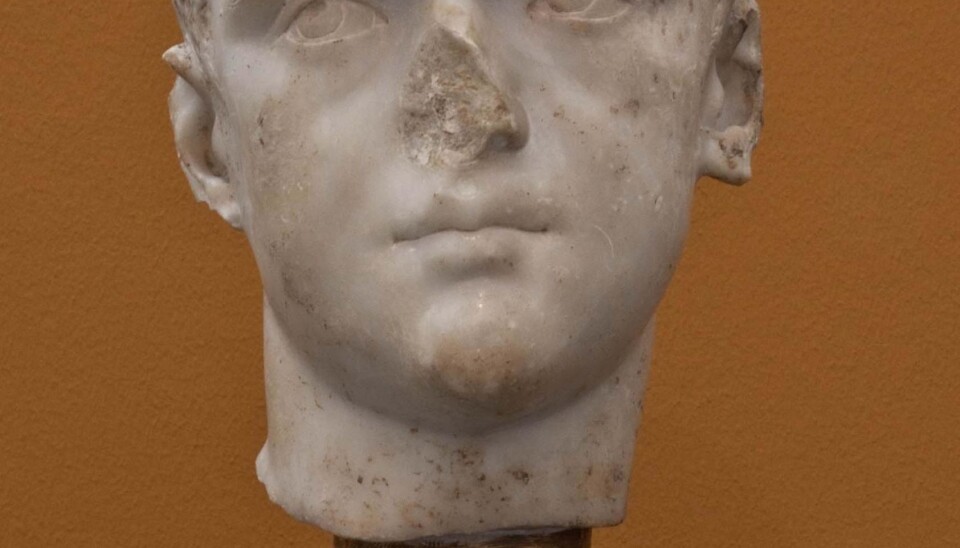

Researchers at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek museum recently started reconstruction work on a copy of the marble sculpture ‘Portræt af en ung romer’ (‘Portrait of a young Roman’).

The sculpture will be polished and painted in order to gain a research-based impression of how the portrait looked in its original state.

”The fine marble can be polished to a very smooth gloss and this particular portrait was definitely painted," he says. "But why go to all this trouble to polish it if it has already been painted? This has probably been because they could create some rather spectacular artistic effects on such a surface.”

Restoring a sculpture in this way is an expensive process, which is why only this one sculpture is being given a high polish.

If you find yourself in Copenhagen in the autumn of 2014, you will have the chance to see this one sculpture, along with a host of other reconstructions, when the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek museum launches its exhibition ‘Farven: den fjerde dimension’ (‘Colour: the fourth dimension’).

------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther