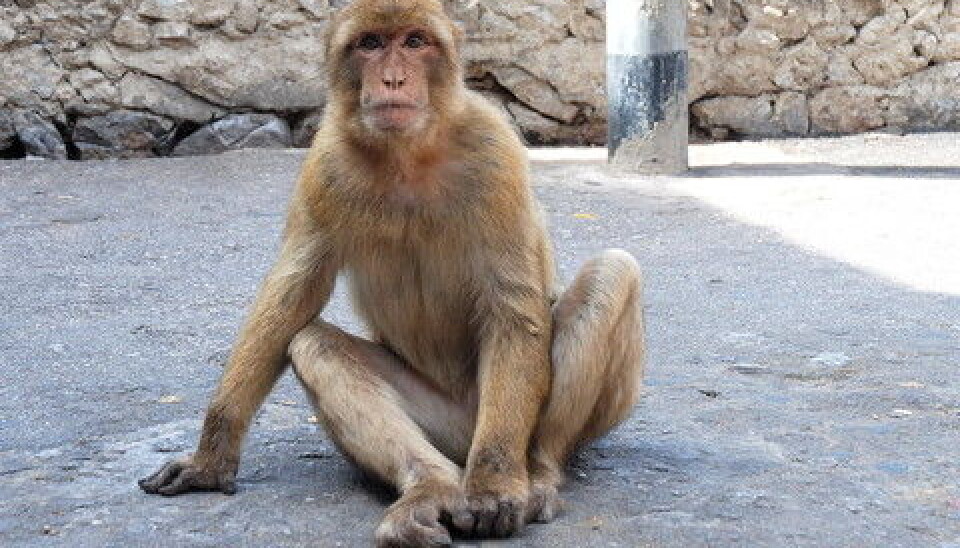

’Loser monkeys’ have poor immune systems

Macaque monkeys at the bottom of the social hierarchy have weakened immune systems. Social status influences almost 1,000 genes that control the immune system. This could apply to humans too.

The genetic expressions in monkeys at the top of the hierarchy are notably different from those of the monkeys at the bottom. What’s more, the genetic expression can change rapidly when the social status is altered.

Among the genes that are influenced by the monkeys’ social hierarchy are those controlling the immune system. This means that social status can influence health – which is probably also true for people.

”We know that social stress can affect health. This is true for people as well as monkeys. We have researched which molecular mechanisms are behind this influence,” says Kasper Daniel Hansen, a post-doc at Johns Hopkins University in the US, who was one of the scientists behind the study.

The result of the study has been published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Scientists used hierarchy and gene chips

Our research is a small step on the way to understanding how stress affects the body on the molecular level. In the long term, it may lead us to find out if it is possible to lessen or remove the effect of stress and understand how the body reacts to its social surroundings.

In the wild, macaque monkeys live in hierarchical structures, where each monkey inherits its place in the hierarchy from its mother. The hierarchical system is constantly adjusted through fights over things like food and water.

However, the system works differently for monkeys in captivity. When a new macaque is introduced to a troop, it is often placed at the bottom of the hierarchy. This gives scientists the opportunity to study how social status influences the genetic expression of the macaque monkey by moving the monkeys around between different troops.

With the aid of a special gene chip technology, scientists were able to measure a specific signature in the expression of 6,000 genes in female monkeys with different social rankings.

They were also able to tell how the genetic expression changed in almost 1,000 genes when the monkeys were moved to another troop where they automatically received the lowest social status.

At the same time, scientists detected a change in the genes of the monkeys that achieved higher social status when monkeys at the top of the hierarchy were moved from the troop.

The study revealed that it only took a few weeks for the genetic expression of a monkey to change following a change in its social status.

The data was so reliable that the scientists could establish the social status of a monkey solely by interpreting its genetic signature.

Genes control the immune system

By comparing the genetic signatures of 49 female macaque monkeys with their social statuses, the researchers found significant changes in 987 genes, 112 of which were connected to the immune system.

Results match previous findings, which have documented that chronic stress in monkeys with low social status results in poor immune systems.

The same applies to people, with economic and social stress increasing the risk of disease. Herpes is an example of a condition that often flares up when a person is feeling stressed.

“We generally expect that our results are transferable to people, but naturally this hasn’t been established yet,” says Hansen.

“Moreover, it is important to bear in mind that macaque monkeys at the bottom of the hierarchy are subjected to more extreme levels of stress than those normally experienced by people. For instance, people are very rarely beaten and bitten by their bosses.”

Stress on the molecular level

Hansen and his colleagues have also studied which mechanisms regulate the genetic expression in relation to the social status of a monkey.

When a macaque has low social status it is chased by the higher-ranking monkeys. This makes them stressed and activates the stress hormone gluccorticoid, which contributes to the alteration of the genetic expression.

The scientists were also able to demonstrate for the first time that methylation of the genes, which is responsible for turning genes on or off, was also influenced by the social status. In monkeys at the bottom of the social hierarchy, genes were often methylated, and therefore turned off.

“Our research is a small step on the way to understanding how stress affects the body on the molecular level,” Hansen says.

“In the long term, it may lead us to find out if it is possible to lessen or remove the effect of stress and understand how the body reacts to its social surroundings.”

Colleague wants to see more

Jan Pravsgarrd Christensen, a lecturer at the Department for International Health, Immunology and Microbiology and the University of Copenhagen, is an expert in the Immune System.

He welcomes the study, but finds that an important element is missing.

“The study confirms what we know about the immune system and stress. Stress hormones regulate a single percent of our genes, so it isn’t surprising that the scientists have reached precisely those conclusions,“ he says.

“I would like to have seen the genetic adjustments related to a study of whether the monkeys were more prone to illness. Often genes can be regulated without directly affecting the immune system, and that still needs to be addressed by the scientists.”

-------------------------------

Read this article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Iben Thiele