Knowing the end goal makes us better team players

When we know what our efforts will end up as, it makes us more cooperative and trusting, study finds.

If you’re about to work alongside other people, chances are everyone will get more from the task if you all know exactly how your efforts are supposed to pan out.

So concludes a recent study by researchers from the interdisciplinary Interacting Minds Centre at Aarhus University, Denmark.

In the study, participants were split into two groups and were told to perform an identical task with only one small difference: the first group was shown a photo of the end result. Surprisingly, this mere alteration made the members of the group express greater signs of cooperation and trust in subsequent tests.

“Knowing the purpose of what you’re doing creates an illusion of trust because you look around and see that all your colleagues are working towards the same goal as yourself,” says postdoc Panos Mitkidis, the first author of the study.

When we trust others we collaborate better with them and we also share more with them, says Mitkidis.

Manipulating people to be more cooperative

The experiment was a two-piece play.

First, 24 male and 24 female participants were divided into groups of four. None of them had met before, which was key to act one of the experiment where the participants were primed for the second part of the experiment. Mitkidis calls this the manipulation round.

After the initial division, the groups were evenly distributed into two categories: transparent groups and opaque groups.

From everyday examples to businesses and how the state should act, I believe that if we know the final purpose of our efforts and focus more on the product rather than the process, then we’ll find it easier to overcome selfishness and engage in truly cooperative tasks.

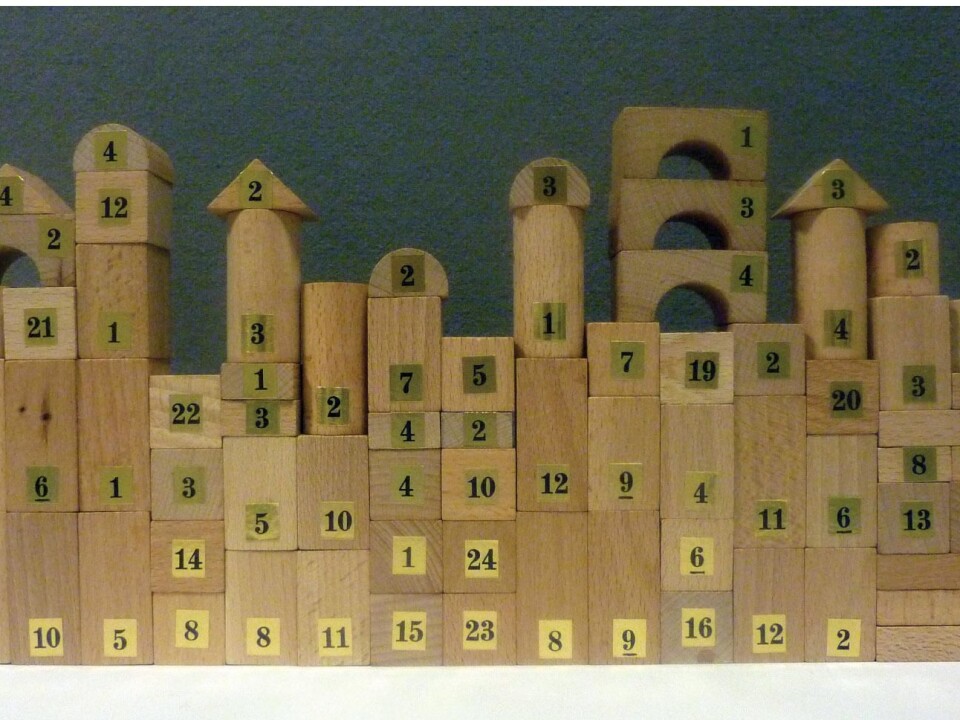

Each group of four were to perform the same task (placing wooden blocks in turns based on instructions from a computer) but only the transparent groups were shown a photo of what they were building prior to the task. The opaque groups saw nothing beforehand and were placing blocks in blindness.

Cooperation springs from playfulness

In many ways the task was similar to building a Lego set. And while the researchers initially had thought of using the popular toy, they chose not to for a specific reason, explains Mitkidis.

”Lego enhances the fun and we really didn’t want people to feel like they were playing but sought rather to incite a sense of seriousness of the task in them,” he says.

The reason, he explains, is that the sensation of fun alone can be enough to make us more cooperative towards others. This could have skewed the results of the second act of the experiment which was all about measuring cooperation and trust between participants from each group.

Money games to test trust and team spirit

To do so, Mitkidis and his research team set up a final test -- a so-called Public Goods Game in which two group members would face each other. Each participant was given €13.50 beforehand and presented with the choice of a) sharing the money in a mutual pool to which Mitkidis in return would multiply the amount by a factor of 1.5 or b) keep the €13.50 for themselves.

Obviously, sharing was the rewarding option but it did not come without a risk because you can’t know if your ‘opponent’ is as cooperative as you.

“If you’re a selfish person your best bet is to keep your own money. As a minimum you’re going to get €13.50 but if the other part shares his money you’re going to walk home with even more,” says Mitkidis.

It is a dilemma demanding trust of your fellow participants, he says, adding that the test is a golden standard for measuring cooperation between human beings.

Transparency made subjects less selfish

Mitkidis’ expectation was that his test subjects from transparent groups would share more because they already knew they were working towards a common goal.

“The more you give, the more you’re cooperating. If both parties put the full amount in the pool it will create a maximum for us as a couple.”

As another safeguard, the players were oblivious to which person from their former group they were up against. They had all met during the manipulation round and certain biases might have arisen then which could distort the outcome, says the researcher.

Instead, each player was placed in a separate room and told to make a decision. Share or keep the money. When decided, they would be marched to Mitkidis’s office for a debriefing and payout – if there was anything to be paid that is.

As it turns out Mitkidis’ initial expectation was right: transparent groups – the ones who were shown what they were building – displayed trust and cooperation to a greater extent. In fact, members of team transparent were 35 percent more likely to share the money than their opaque counterparts.

Participants may have been entertained by teamwork

The test subjects were also asked to fill out a questionnaire so the researchers could assess the emotional response to the experiment.

Interestingly, transparent groups reported much higher satisfaction with the block building task compared to the opaque groups.

Seventy-five percent of the people in the transparent condition felt the process was entertaining while the opaque condition only elicited an “entertaining” rating from 42 percent of the participants.

The researcher sees it as a side effect of the study rather than a real effect.

“That’s why we didn’t focus on it,” he says, but does offer an explanation:

“Knowing what you are doing and that the people around you are working towards the same thing makes you have more fun. I think that that’s quite interesting. Maybe that’s something that partly drives cooperation in the end.”

Working together is hard

However, all wasn’t joy in the transparent groups. Having the end result revealed before the test made the test itself seem much more difficult. In fact, only 13 percent found the transparent test easy while the opaque number was much higher, 38 percent.

“I think it has to do with the opaque test being much more individual,” says Mitkidis.

People in the transparent condition would commence the building with a fresh imprint of the goal stuck to their inner eye. In comparison, the opaque group members would feel like they were simply placing bricks in a pattern that might as well be random.

“When you construct something with three people and you don’t know exactly what the final goal is, it is kind of easier to report that something is easy,” says Mitkidis.

“But if you come to me and tell me: ‘Do that!’ – and you follow up asking whether it was easy or entertaining I would definitely tell you it was easy but not fun.”

Building society on trust and collaboration

The researcher says that the result is also translatable to everyday life. He exemplifies it with an anecdote (maybe authentic) from the kitchen:

“If you want to help your girlfriend with the dinner, you might know where all the ingredients and utensils are but if you don’t have a clue about what she’s cooking it’s going to be very difficult to help and the food is probably going to turn out very bad,” he says.

It may sound trivial but the basic idea is to keep an eye on the goal. This is important, explains Mitkidis, pointing at the Danish tax system as a good example of cooperation as a result of trust.

“If I didn’t trust the system – like it is in very corrupt countries – then I wouldn’t pay tax because I wouldn’t trust other people. But Danes pay their taxes because they trust the system and know that what they pay will be repaid to them as a group and not just the individual.”

-------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Kristian Secher