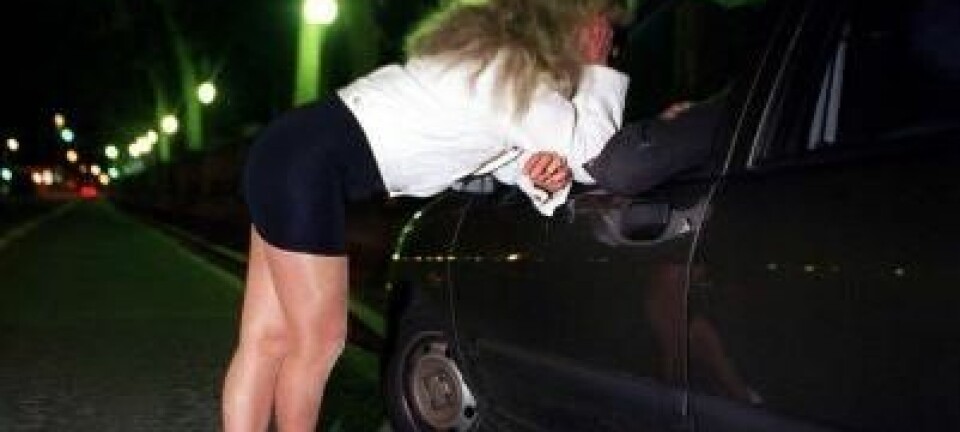

Selling sex solves problems for prostitutes

Women who sell sex on the streets do not perceive their sex trading as negatively as their surroundings do. They primarily regard their activities as an effective way of solving their financial problems.

If only we could get the street prostitutes to stop selling sex, their lives would improve. This appears to be the prevailing view among Danes – including those whose work consists of helping prostitutes.

However, you gain an entirely different perspective if you take a closer look at the lives that these women live.

This is the view of Jeanett Bjønness of Aarhus University’s Department of Culture and Society, who has just defended her PhD thesis about prostitution, drug abuse and the fight for recognition among marginalised Danish women.

She has interviewed 40 Danish women who sell sex on the streets, and it turns out that the women do not regard their sex trading as the biggest problem in their lives. To these women, the real problems are a lack of trust from their surroundings, homelessness, poor personal finances, drug abuse, the relationship with their children and the social system.

”Sex trading is not regarded as the main problem. In fact, it is perceived as a solution to some problems,” says Bjønness.

Selling sex is better than crime and drug-dealing boyfriends

From 2001 to 2005, she carried out her ethnographic fieldwork at a drop-in centre for women who trade sex and take drugs. She visited the centre on a daily basis and became a part of the women’s daily lives. She joined the women on holidays, for birthdays, funerals, treatment, in prison, at the hospital and she even visited some of the women’s children.

This meant that she forged a close relationship to the street prostitutes – or ‘women who sell sexual services’, as she prefers to call them because this is more in line with the women’s own self-image.

“When I started on my project, I believed – just like my surroundings – that sex trading was the biggest problem in these women’s lives,” she says.

When I started on my project, I believed – just like my surroundings – that sex trading was the biggest problem in these women’s lives. But as I got to know them better I realised that they actually perceive their sex trading as the solution to their financial problems. That’s something I found very, very hard accept.

“But as I got to know them better I realised that they actually perceive their sex trading as the solution to their financial problems. That’s something I found very, very hard accept.”

She explains that:

- The women describe the selling of sexual services as the easiest solution to their financial problems.

- They get a feeling of independence. Sex trading can provide them with a feeling of being independent from boyfriends, drug dealers and criminal activities. It pays for the drugs that help them make life bearable in the short term.

”I found that the those we usually think of as victims often tend to be incredibly creative, intelligent and strong women who try to take responsibility for their lives – partly by selling sexual services. They regard the money earned from their sex trading as ‘easy money’, compared to the alternatives: committing crime or dating a drug dealer.”

Sex trading not a free choice

The women see sex trading as a free choice, but according to Bjønness’s analysis it is not a free choice.

To understand how sex trading can be viewed as the easiest solution, we need to take an interest in the women’s backgrounds. It’s often a background with poverty, unemployment, drug use, homelessness – and, not least, a general loss of trust in the social system. They feel that there is a shortage of alternatives to sex trading.

She has analysed the women’s situation based on a theory by the French sociologist Pierre Bordieu, which states that we only have the freedom of choice that we get through our relationships and our experience.

The women in the study had very limited education and little experience with the labour market. Their network is primarily to be found in the street environment or at the social office – and that limits their freedom.

“The women do not make a free choice, but they get the best out of the perceived opportunities. So when debaters and the social system seem to encourage the women to stop selling sexual services, it is essential that the women are also asked what it would take to do so,” she says.

“To understand how sex trading can be viewed as the easiest solution, we need to take an interest in the women’s backgrounds. It’s often a background with poverty, unemployment, drug use, homelessness – and, not least, a general loss of trust in the social system. They feel that there is a shortage of alternatives to sex trading.”

Branded as a prostitute

In the interviews they emphasize the reasoning behind their decisions and the contexts that can make their decisions understandable to their surroundings. Their trust in other people disappeared, they needed drugs to soothe themselves and the sex trading was necessary to get money for drugs. In other words, it’s not the people that are different; it’s the context they live in.

It may seem as if the women think of sex trading as an entirely positive thing, but that’s not the case:

“Sex trading is paradoxical for the women. It solves some problems, but at the same time it creates new ones. To other people, sex trading is so unacceptable that it becomes an all-encompassing part of how they regard these women,” says Bjønness.

“It becomes a prism through which all other aspects of their lives are viewed. It becomes hard for the women to be regarded as anything other than ‘a prostitute’ with all the negative things that are associated with it.

Even the social authorities – and drop-in centres too – have long had an unfortunate tendency to primarily regard the women as ‘prostitutes’, says the researcher.

“A certain type of ‘radical feminism’ has had a strong position. It has perceived the prostituted women as different, as victims of male violence. The women are assumed to need help to get a better life – and not least to make the right choices.”

The women do not see themselves as victims

Bjønness believes that the people whose job it is to help sex workers often tend to ignore how these women perceive their own situation. This, she says, is because social workers are used to regarding the women as victims.

This rigid view of sex traders has the consequence that the women feel walked over, because they do not see themselves as victims. The see themselves as independent women who make rational choices based on the options available to them.

“In the interviews they emphasize the reasoning behind their decisions and the contexts that can make their decisions understandable to their surroundings.

“Their trust in other people disappeared, they needed drugs to soothe themselves and the sex trading was necessary to get money for drugs. In other words, it’s not the people that are different; it’s the context they live in,” says Bjønness.

We ought to take sex traders seriously

The new thesis does not provide any conclusive solutions to how social authorities should deal with women who sell sexual services.

However, Bjønness is adamant that we as a society should start listening to what these women have to say.

To many of the women, the prostitution is not their problem. For them it can be a bigger problem that they feel let down and out of place, are homeless, rarely see their children or have serious relationship problems.

”We need to listen to them. We need to take an interest in them and their perspectives on life, rather than feeling sorry for them. We need to ask them, ‘How are you?’ and ‘What problems do you face in your life?’ – and then actually take what they say seriously.”

The researcher believes that further research based on this approach to the women may help improve the social services available to them in the future.

-------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk