Prehistoric humans were far smarter than previously assumed

325,000-year-old stone tools go to prove that our forefathers were far better at collaborating and planning than we thought.

An international study sheds new light on our cave-dwelling forefathers who lived more than 300,000 years ago.

The new study recently published in Science reveals that our forefathers were innovative thinkers who time and time again found new and better ways of doing things.

The study shows, among other things, that an especially advanced technique used to make stone tools was not just discovered once and then simply copied. Instead, the technique was discovered many times at different points in time across the globe -- which suggests that our forefathers were generally more resourceful than previously thought.

Nathan Wales, a Post-doc at the Centre for Geogenetics at the University of Copenhagen, is one of the researchers behind the new study. He explains:

"It has long been debated as to whether the Levalloisian technique of flaking stone to make tools was discovered once, at one point in time somewhere in Africa and then spread across the globe by migrations or whether it was discovered on several occasions at different points in time. Our study shows that the technique was discovered several times, and this casts entirely new light on our forefathers' ability to think innovatively.”

Wales was involved in the research while studying at the University of Connecticut, USA.

Danish researcher enthusiastic

Although Professor of human evolution at the Centre for Biocultural History, Peter C. Kjærgaard, was not involved in the new study, he has read it and is extremely enthusiastic.

He says the study emphasises once again that our view of our forefathers has been grossly oversimplified and that we for far too long have confused a simple explanation of mankind's history with a simple story -- the theory that our forefathers only developed a given technique once.

"In scientific studies of human history we have focused for far too long on the crucial importance of unique events,” says Kjærsgaard. “I know we’ll be seeing many more of this kind of studies which underpin the fact that the history of mankind and our evolutionary relatives is characterised by being able to adapt to local conditions rather than our idea of a simple history of origins that is still largely borne by religiously founded wishful thinking according to a biblical narrative.”

Little difference between them and us

According to Wales, the study's conclusions give us entirely new insight into how our forefathers lived.

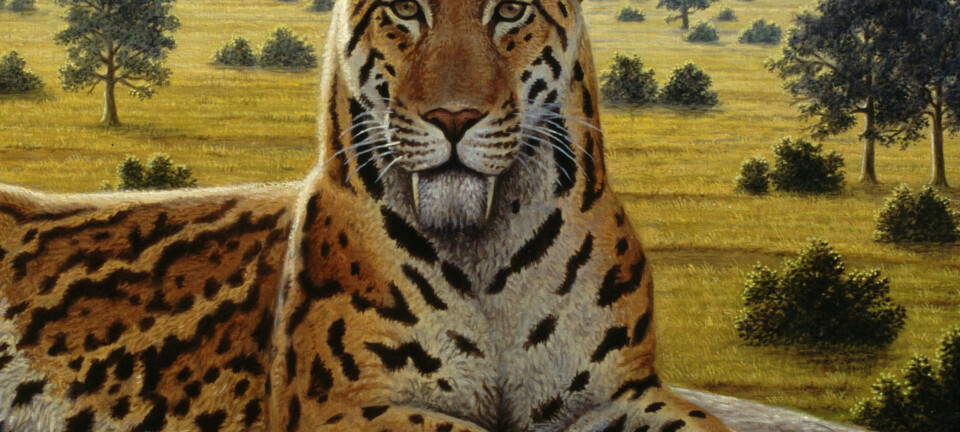

Some 325,000 years ago, Homo sapiens had neither emerged nor immigrated from Africa, and our close forefather Homo heidelbergensis, whom the researchers suspect were behind the stone tools, have not been credited with many human cognitive qualities.

But Homo heidelbergensis probably possessed these qualities to a much larger degree than we believe.

"Homo heidelbergensis was probably a lot more human than we thought. We have this idea that only modern humans have been innovative enough to keep coming up with ideas for technological progress while other early humans discovered things once and then continued to make them the same way afterwards. This study shows that there probably wasn't much difference between them and us," says Wales.

Stone tools caught between two volcanic eruptions

The researchers examined stone tools found in Nor Geghi in central Armenia.

Researchers normally have great difficulty determining the age of stone tools but near Nor Geghi, volcanic eruptions encapsulated stone tools between two volcanic strata dating back 400,000 and 200,000 years respectively.

Because the two volcanic strata preserved the stone tools where they were abandoned, the researchers were able to date them very precisely to between 335,000 and 325,000 years ago.

"It is seldom indeed that we can date stone tools so precisely -- because you can't use carbon dating on stone," says Wales.

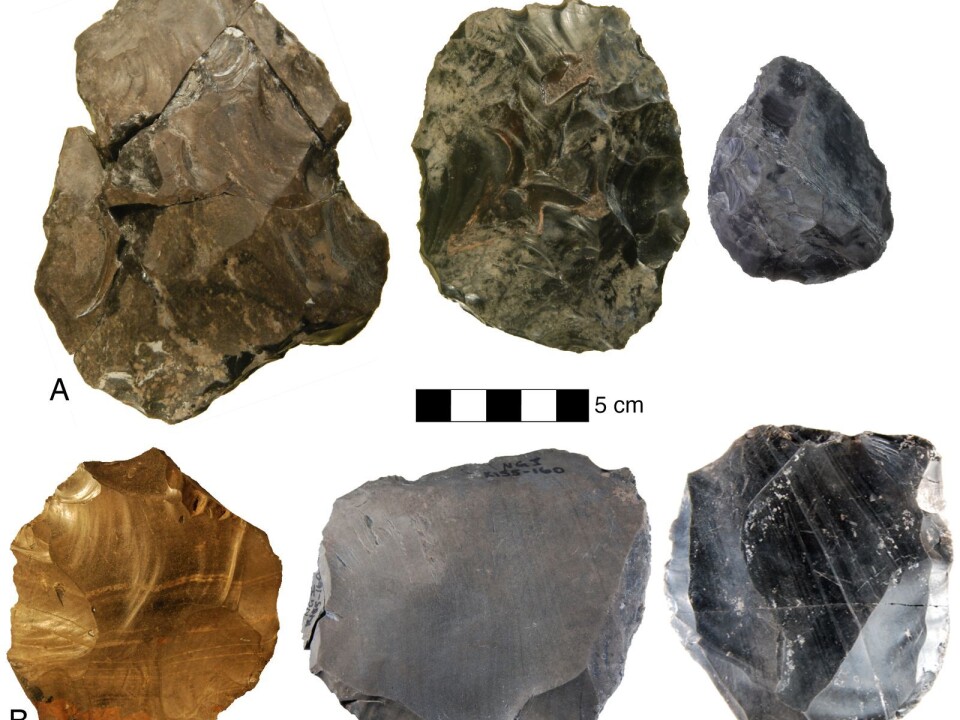

At the same time, the researchers could see that the stone tools, which were made using two different techniques, came from the same period. The researchers found stone tools made using the Levalloisian technique, which enabled our forefathers to make more than one sharp tool from one piece of rock (see fact box).

"We usually say that the Levalloisian technique took over from an older, less advanced method. But at Nor Geghi we can see that both techniques were used during the same period. The Levalloisian technique was not one brought from some place of origin in Africa but to a high degree a technique devised to locally or regionally," says Wales.

Same picture the world over

When the researchers acknowledged the fact that the Levalloisian technique could have been discovered more than once they started to examine more finds of stone tools from different parts of the world

They examine several thousands of stone tools made using the Levalloisian technique or the more primitive technique.

Their examinations showed that Nor Geghi was not a unique place but that the Levalloisian technique had been discovered on several different occasions at different points in time at different locations in Africa, Europe, and Asia.

The main author of the new study, Professor David Adler from the University of Connecticut in the United States, explains in an email to ScienceNordic how the finds from Nor Geghi complement finds from the rest of the world:

"If the theory of a single place of origin were to be true, we would see that the Levalloisian technique would take over entirely from the old technique after it had been introduced in one area.”

“This is not the case in Africa, Europe and Asia where we often find tools that show that the two techniques replaced each other by turns," writes Adler.

Why the technology disappears again

Felix Riede, a lecturer in prehistoric archaeology at the Department of Culture and Society at Aarhus University, also thinks the new study is very exciting.

However, the conclusions do not come as a surprise to him.

"We’ve gradually found more and more evidence pointing to the fact that our forefathers had the capacity to be innovative and that this goes much further back in time than we once believed. That's why it doesn't surprise me," says Riede.

Riede has, however, noticed one extremely interesting aspect of the new study which points to a reason why the technique was discovered repeatedly only to disappear again.

"The study clearly illustrates how population density at the time was very important when it came to innovation. If the population density was low there was a greater risk of a group that possessed developed technology dying out -- for which reason techniques had to be rediscovered."

"If on the other hand the population density was high there was a greater chance of the technology taking root and spreading. This supports the idea that demography was decisive when it came to the potential of technological complexity among our forefathers. Low population density may be the reason why we only find sporadic innovation in this early Stone Age," says Riede.

Walked 120 km carrying rocks

Wales points to another interesting aspect of the study: the stone tools were made from rocks retrieved 120 km away from where the tools were found.

That means Homo heidelbergensis were able to plan out retrieving the rocks and then turn them into tools later on.

According to Wales, one possible scenario is that some places had been good for hunting while others had the best stones with which to make tools.

Homo heidelbergensis knew where to find what.

"Using things that are more than 120 km away requires an enormous amount of planning. I very much doubt that there are many people these days who could find a rock formation 120 km away,” says Wales. “The find suggests that Homo heidelbergensis precisely planned the group's movements and we can use this to get a better understanding of how they lived in and exploited the landscape.”

Our forefathers served apprenticeships

The development of the Levalloisian technique also tells the researchers a lot about what life was like for Homo heidelbergensis.

It was a technique that was very difficult to master, most likely requiring years of hard effort, says Wales.

The complex technique suggests some form of knowledge exchange took place between the generations. Perhaps a father or grandfather allowed a young boy to follow them doing their work with stone and help them in their own experiments.

"Of course we can't know how this actually happened, but it does suggest that Homo heidelbergensis lived a life that wasn’t much different from that of more recent hunter gatherers," says Wales.

----------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews