Metabolism works differently than we thought

Kleiber’s law of metabolism, which states that the metabolic rate of an animal scales to the 3/4 power of the mass, has a flaw in it, argues Danish scientist.

Kleiber’s law of metabolism, which states that the metabolic rate of an animal scales to the 3/4 power of the mass, has a flaw in it, argues Danish scientist.

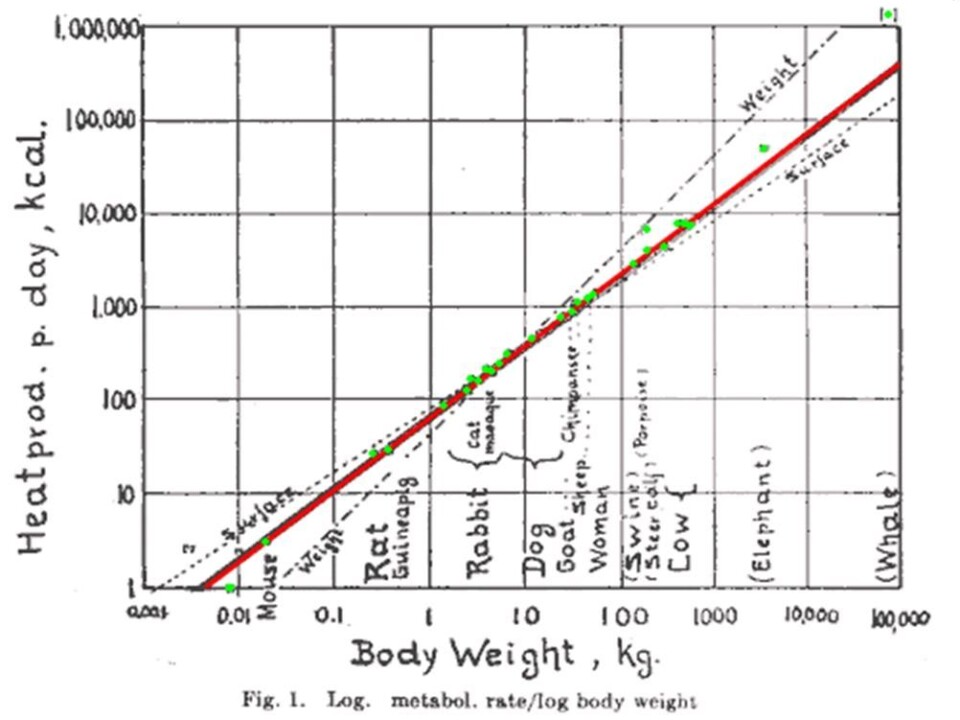

The so-called ‘3/4 law of metabolism’, proposed by Max Kleiber in 1932 as "extended to all life forms", has a previously overlooked flaw, argues Danish scientist.

A good understanding of animal metabolism – how they convert their food into energy – is crucial for animal farmers to feed their animals correctly.

To get an idea of how much food an animal requires, farmers often use Kleiber’s law – the observation that for the vast majority of animals, an animal's metabolic rate scales to the ¾ power of the animal's mass.

However, this law has a flaw, argues Professor Thomas Kiørboe of the Centre for Ocean Life at the National Institute for Aquatic Resources at the Technical University of Denmark:

“Kleiber’s law works as long as it is limited to describing only individual groups of organisms, such as bacteria, fish and mammals. But as soon as we switch from one group to another – for instance from bacteria to invertebrates, Kleiber’s law no longer works.”

Kleiber’s law states that our metabolism does not grow proportionally with our body weight. This means that if a person weighs 50 kilos and another weighs 100 kilos, the heavier person’s metabolism is not twice as high. If two people or animals of different weight were to swap metabolism, mysterious things would happen, according to Kleiber’s law.

Kiørboe uses as an example a mouse and an elephant swapping metabolism:s”The mouse would not have enough drive power. It would come to a stop because the elephant’s metabolism, viewed in relation to its own body weight, is lower. The elephant would start to boil because the mouse’s metabolism would burn much more energy.”

He adds that Kleiber’s law holds true and makes good sense – but only to a certain extent.

Kleiber’s law works as long as it is limited to describing only individual groups of organisms, such as bacteria, fish and mammals. But as soon as we switch from one group to another – for instance from bacteria to invertebrates, Kleiber’s law no longer works.

Kiørboe and his British colleague Andrew G. Hirst have spent two years studying data from various groups of organisms and animals in the sea. This included looking at the animals’ metabolism, their ability to find food and how much they grow.

“What is surprising is that when viewed across the spectrum from the smallest organism to the largest animal, the metabolism, as well as the ability to find food measured in relation to the size of the organism, only varies by a factor of 100 between the animal groups. This is inconsistent with Kleiber’s law, which states that the metabolism changes by a factor of 1,000,000.”

Other scientists have previously pointed to the same flaws in Kleiber’s law, including Danish researcher Axel Hemmingsen in the 1960s.

_______________________

Read the Danish verision fo this article at vienskab.dk