Melting sea ice makes deep-sea animals grow

Scientists are now able to film and observe how life at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean is affected by global warming.

Eat more and you’ll grow bigger – also if you’re a deep-sea fish at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean.

An international research team has been filming and observing how life at the bottom of the deep sea in the central Arctic is affected by global warming.

At four-kilometre depths, they observed how animals such as sea slugs and brittle stars grow bigger than normal and also how they reach sexual maturity at an earlier age.

The team notes that the reason for this is to be found in the melting sea ice four kilometres above these animals.

For the first time ever, we have managed to demonstrate that global warming and the resulting environmental changes in the central Arctic can trigger rapid reactions in the entire ecosystem, all the way down to the deep ocean.

This is an important discovery because up to now researchers have been assuming that life at such depths is not affected by climate change on the Earth’s surface.

“For the first time ever, we have managed to demonstrate that global warming and the resulting environmental changes in the central Arctic can trigger rapid reactions in the entire ecosystem, all the way down to the deep ocean,” says Professor Antje Boetius, of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Germany.

Open waters provide space for algae

The team consisted of researchers from 12 countries. The Danish contribution came from PhD student Heidi Louise Sørensen and Karl Attard, of the Nordic Centre for Earth Evolution (NordCEE) at the University of Southern Denmark.

The research expedition lasted nine weeks and took place on board the German research vessel Polarstern.

We cannot say whether we have observed an isolated phenomenon or whether it will appear again in the coming years.

The findings reveal that the animals on the seabed grow bigger and fatter than normal because they are eating unusually large amounts of food

The food is the so-called sea-ice algae, which sink down from the sea surface. As the sea ice melts, an increasing amount of sea-ice algae are produced, and this results in more food for the animals that feed on these algae.

Sea-ice algae grow beneath the sea ice, and since the sea ice used to be thicker than it is today, their number and size have so far been kept in check by the limited light that could penetrate through the ice.

Just like plants on the Earth’s surface, sea-ice algae depend on sunlight to grow.

As the sea ice melts and thins out or disappears, the sea-ice algae receive more sunlight, which then makes them grow in size and number. They accumulate and can form seaweed-like colonies that hang beneath the ice.

Sea slugs gorge on windfalls

When the sea-ice algae break off, or when the ice disappears and they no longer have anything to stick to, the algae are so heavy that they can sink all the way down through the water and land on the bottom of the sea four kilometres below.

Here they get eaten by organisms such as sea slugs and brittle stars, which use the abundance of food to grow bigger and speed up their sexual maturity.

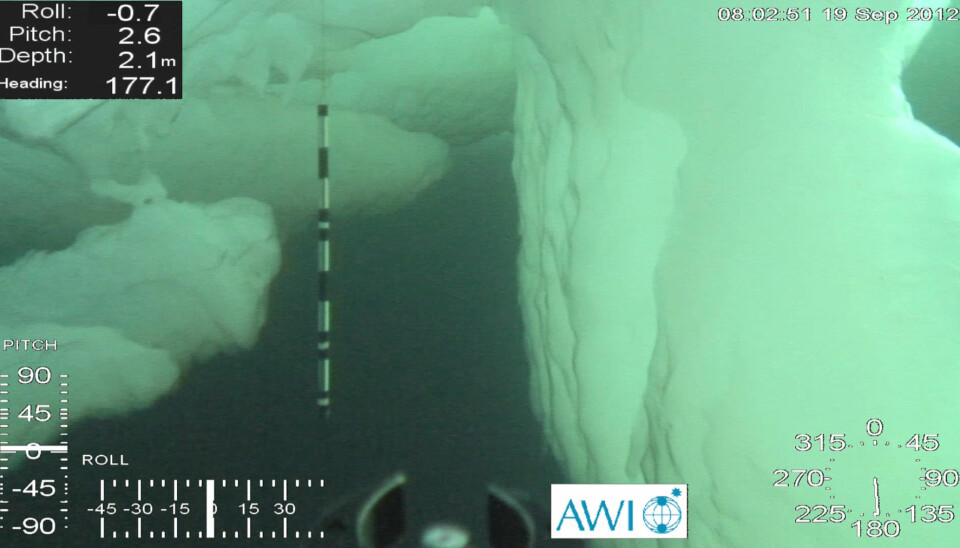

It’s thanks to a new camera system known as Ocean Floor Observation System (OFOS) that the researchers now know how life at the bottom of the sea responds. OFOS has made it possible, for the first time ever, to film and observe the aquatic wildlife and the enormous amounts of sea-ice algae on the seabed.

OFOS filmed at many different locations in the central Arctic and found that up to 10 percent of the seabed was covered by lumps of sea-ice algae. Some of these lumps measured up to 50 centimetres in diameter.

Further studies needed

The researchers made their observations in the summer of 2012, and since nobody has previously monitored the growth of algae below the central Arctic sea ice, they cannot say with any certainty whether this increase in growth has also taken place in the summers that have passed since global warming set in.

“We cannot say whether we have observed an isolated phenomenon or whether it will appear again in the coming years,” says Boetius.

They do, however, know for certain that the ice cover has shrunk over the past 50 years during which researchers have taken satellite photographs of the sea ice distribution in the Arctic Ocean.

-----------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk