Even tiny oil spills may break Arctic food chain

Drilling for oil in the Arctic may have catastrophic consequences, new study suggests.

As the Arctic ice is melting, areas that used to be covered by a thick layer of ice become accessible.

These areas contain great amounts of oil and are therefore of great interest to oil companies.

However, according to a new study, drilling for oil in these areas can have disastrous consequences if the increased ship traffic, and the possible oil spills, increase the amounts of oil in the ecosystem.

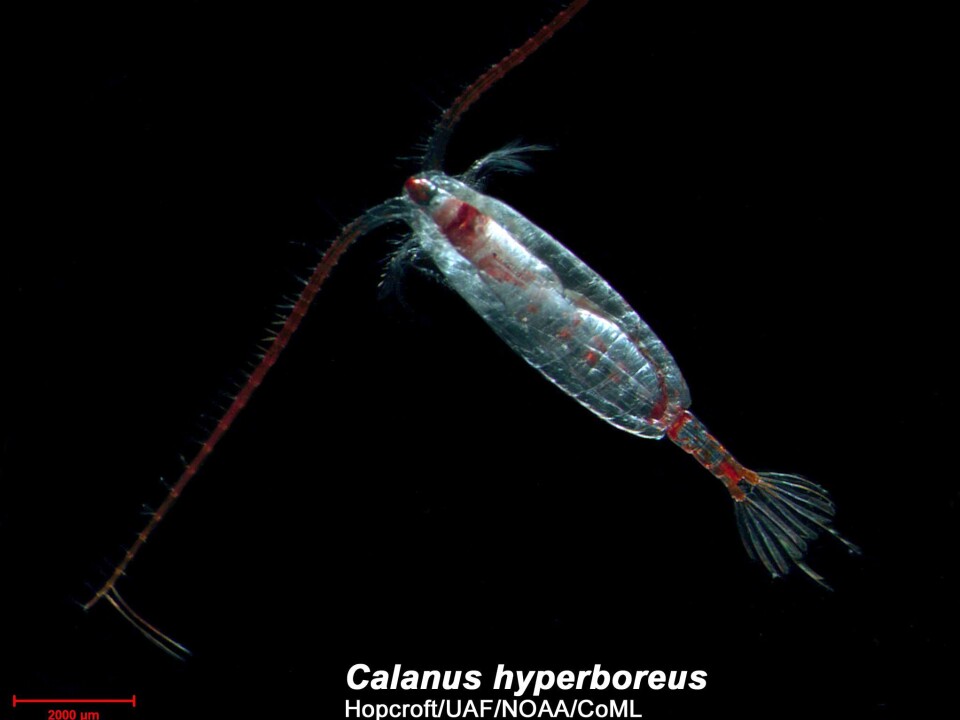

One of the cornerstones of the Arctic food web – the copepod species Calanus hyperboreus – responds particularly poorly to even the tiniest amounts of oil in the water, and once these copepods run into problems, the entire food chain – with everything from fish to humans in it – also runs into problems.

So says Professor Torkel Gissel Nielsen, of DTU Aqua at the Technical University of Denmark, who co-authored the new study, published in the journal Ecotoxicology.

“There are huge oil reserves in the Arctic. When we start extracting them, there will inevitably be spillage at some point,” he says.

“Our research shows that it only takes tiny amounts of oil in the sea to significantly reduce copepod egg hatching rates. If there are no copepods in the sea, there is no food for the fry. Even tiny oil spills in the Arctic can end up breaking the food chain entirely.”

Why copepods are important

The reason that the C. hyperboreus is a key species in the food chain is that it is the food source of virtually all fish in the ocean. The copepods feed on algae and thus convert the algae into food for other animals.

Our research shows that it only takes tiny amounts of oil in the sea to significantly reduce copepod egg hatching rates. If there are no copepods in the sea, there is no food for the fry. Even tiny oil spills in the Arctic can end up breaking the food chain entirely.

The total weight of the copepod population also exceeds the weight of all other aquatic animals, so even though each individual copepod is less than one centimetre in length, they collectively make up a considerable amount of food for fish, birds and crustaceans.

A reduction in the copepod population, or a mere displacement of the various copepod species, will therefore have catastrophic consequences for a wide variety of other animals, too.

Fatty copepods are most important

In their study, the researchers specifically looked at the C. hyperboreus, as this is the fattest one of the Arctic copepods and thus also the most important one in this context.

In the Arctic, fat is key to survival, and without the fatty copepods, there is less fat being transported from algae up through the food chain, first to copepods, then to fish and birds, and lastly to whales, seals, polar bears and humans.

An oil spill can therefore have the consequence that an entire generation of C. hyperboreus is wiped out. This will result in an entire generation of fry also losing a key food source, as they have no fatty copepods to feed on when preparing for the cold winter,” says the professor.

“If the number of these fatty copepods is reduced as a result of oil spills in the ocean, it is possible that they will be replaced by other species,” says Nielsen.

“However, for animals that feed on the copepods, this would be similar to changing from a diet of bacon to one of rice crackers and still being able to stay warm through the Arctic winters. That is not possible, and many species will be experiencing great problems.”

Oil prevents eggs from hatching

The problem with the C. hyperboreus is that its eggs are much more susceptible to oil exposure than eggs from other species.

Most copepods have hard eggshells, but C. hyperboreus eggs are only covered by a thin membrane. This membrane is permeable to organic substances such as oil, which can penetrate the egg and kill it.

“An oil spill can therefore have the consequence that an entire generation of C. hyperboreus is wiped out. This will result in an entire generation of fry also losing a key food source, as they have no fatty copepods to feed on when preparing for the cold winter,” says the professor.

Oil enters the food chain

In their studies, the researchers exposed the copepods to very small and realistic amounts of oil in the laboratory. The oil concentrations corresponded to the amount of oil that can be expected from a small oil spill.

The oil turned out to cause a sharp reduction in the number of hatched eggs. The oil also affected the female copepods which, although they did not die, became less active and ate less.

However, the apparent fact that the copepods survive the small doses of oil is a problem:

”It means that the oil enters the food chain, and that means it may affect other animals whose response to the oil we still do not know. This is another problem caused by oil spills in the Arctic.”

---------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk