Researchers' Zone:

The great retreat: Climate change is pushing the muskox back north -can they keep up?

40 years of data show that climate change in the Arctic is forcing muskoxen to find new habitats. And it is not alone - other species must do the same

The muskoxen are the largest plant-eating

animals roaming the Arctic tundra.

Muskoxen have successfully survived previous ice-ages and hot-spells by constantly moving towards areas with optimal living conditions.

Over time, this has led to a distribution of these hairy beasts that covers large parts of the Arctic region.

This makes the muskoxen a good example on how climate largely influence where

animal species live and what kind of habitats are good for them in terms of survival and reproductive success.

When local climatic conditions become unfavorable, wild animals normally move into more benign, often new areas.

This ‘tracking of climate’ by wildlife is a natural process and has been happening for millennia.

Since the late 19th century, the

climate has changed like never before.

The Arctic is now warming 4 times faster than other regions on Earth and this is unlikely to stop in the foreseeable future.

This is potentially bad news for Arctic species like the muskox that have evolved to thrive in the cold.

Extreme northward shift of climate suitability

To find out how recent climate change has

impacted which geographical areas are suitable habitat for muskoxen, we (a

group of scientists from Aarhus University) analyzed observations of muskoxen,

and recently

published our results in Climatic Change.

The observations are collected over the last 40 years in the Northeast Greenland National Park (from here on called NGNP) by the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol, a special unit within the Danish defense.

A Sirius patrol

consists of 6 dog sled teams, each conducting one trip in spring and one in

autumn. Trips typically last several months during which over a thousand

kilometers are covered.

All wildlife spotted by Sirius are recorded specifying date, species and location of the observation.

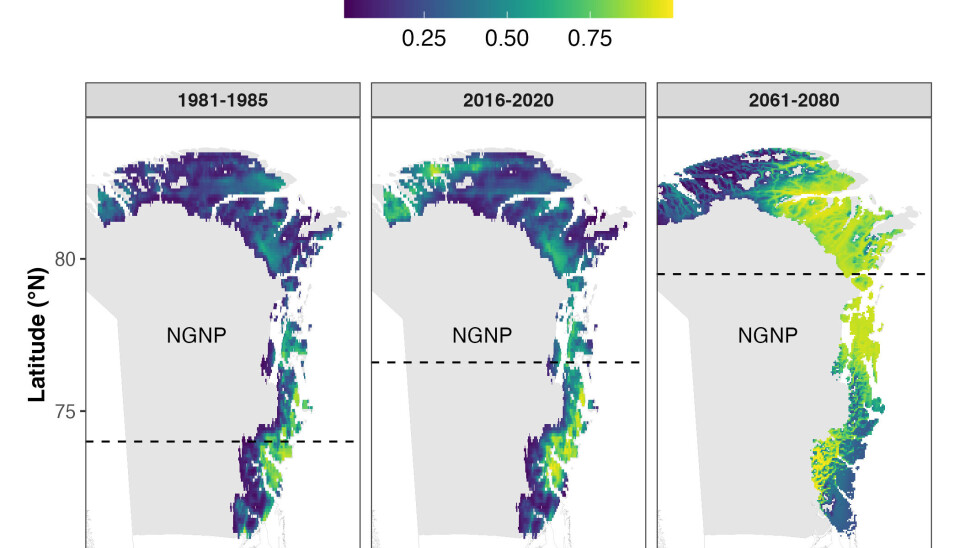

Based on these data, results of our study showed that climatic changes that have happened over the last four decades in the world's largest land-based protected area has pushed the optimal habitat for muskoxen northward really fast (see the figure below).

Changes

are accelerating since the turn of the century

The rate of change between 1981 and 2020 corresponded to 69-108 kilometers per decade, which is approximately the width of Sjælland every 10 years.

At the same time habitats in the south became increasingly sub-optimal.

The northward shift in habitat suitability happened even faster after the year 2000 when the temperature and weather started to get even more abnormal.

Compared to other areas and species around the world, this study highlights that muskoxen are experiencing some of the most extreme habitat shifts as a consequence of recent climate change.

Future climate will reshuffle species’ distribution

A logical follow-up question is then: what about future climate change?

How will the expected and continued warming during this century determine where muskoxen and other Arctic animals can live in the NGNP?

To try and answer these questions, we turned to the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol data again, this time also including observations of other charismatic Arctic species, such as the Arctic fox, Arctic hare, Arctic wolf, polar bear, rock ptarmigan, snow bunting and snowy owl.

The muskox will get company further north

We combined all sightings data for these species with climate forecast models up until the year 2080 (see figure above).

The study results showed that muskoxen but also the other 7 species are expected to be pushed even further north as the climate continuous to change over time.

Importantly, the speed at which the different species will move northwards is expected to vary greatly.

That can lead to a re-shuffling of wildlife distribution in the national park under future climatic conditions.

Can they keep up?

Collecting long-term location data of wildlife across large areas in the high-Arctic is extremely challenging and expensive, and thus rare.

The data collected by the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol are unique and the most extensive currently available for the Arctic region.

Thanks to these data and the results of both these studies, we now know that muskoxen have, and will continue to be, impacted by climate change.

Muskoxen and other Arctic species living in the NGNP will need to retreat to northern Greenland fast to maintain their survival and maximize reproductive success.

The burning question now is whether muskoxen and other Arctic species living in the southern parts of the NGNP can keep up with the rapidly changing conditions as they are tracking their optimal climate further north.

Evidence from Zackenberg

Roads and fences are known to limit animal migration in human-dominated landscapes, but fortunately these human barriers are absent in the NGNP.

Instead, the region has various natural barriers such as deep fjords, glaciers, and steep mountain ranges, which can make it difficult for muskoxen in the south to track the northward shifts of suitable habitat and favorable climatic conditions.

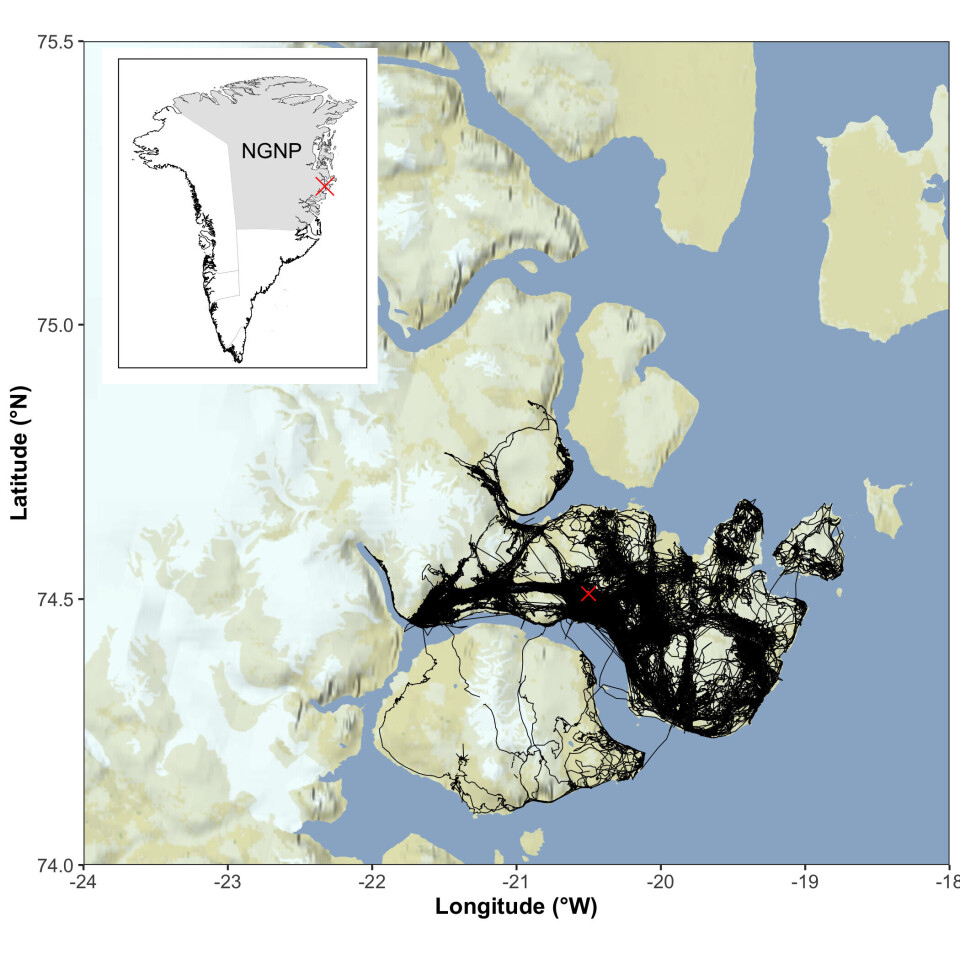

In another study 61 individual muskoxen were fitted with Global Positioning System collars to collect movement data from these big animals.

The results have not shown any long-distance or northward migrations away from the collaring site at Zackenberg valley (74°2N, 21°3W) located in the southern part of the NGNP (see figure below).

Is migration even possible for the muskox?

This could either mean that the Zackenberg valley is still an optimal place to live for muskoxen, or, alternatively, that muskoxen are unable to migrate further north.

If muskoxen in the NGNP are in fact limited in their migration capacity, this could lead to the gradual demise of southern populations.

They become trapped in increasingly poor habitat and unfavorable climatic conditions, while populations in the north may be less impacted under current (and future) habitat and climate change.

While muskoxen and other Arctic species living on the NGNP tundra are not yet in grave peril, their long-term persistence and survival is, and will continue to be, challenged by the rapidly changing climatic conditions across the high-Arctic.