5,000-year-old cob reveals the origins of corn

Genetic analyses of a 5,000-year-old corncob shows how early farmers modified what would go on to become one of the world’s most important crops.

A team of scientists have mapped the genetic material of a 5,000-year-old corncob from Mexico, and have discovered how early agriculturists shaped the development of what is today one of the world’s most important crops.

“Corn is the most important crop that we have today. It grows all around the world and it’s really interesting to find out how it became so important,” says lead author Nathan Wales, a postdoc from the Centre for GeoGenetics at the Natural History Museum of Denmark and the University of Copenhagen.

“It’s an exciting study and the oldest known corn-genome of high quality,” says postdoc Kelly Swarts from the Max Plack Institute, Germany. Swarts studies the history of corn but was not involved in the new research.

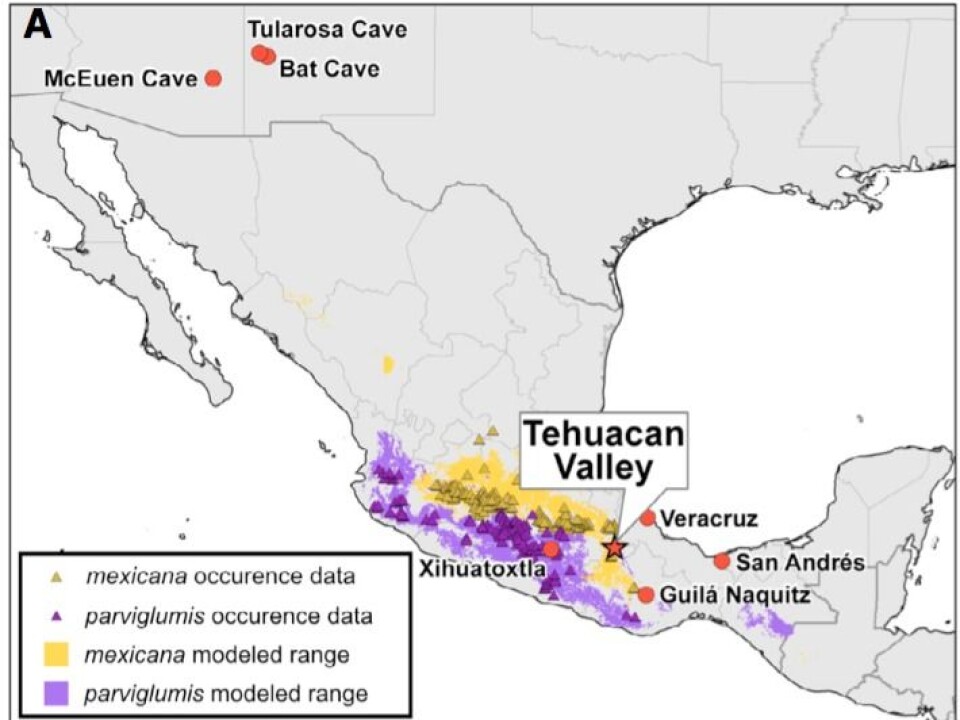

“The genome reveals that all present-day corn descends from this area of Mexico, and it supports the hypothesis that corn was domesticated in the lowlands first, and then cultivated in the highlands before the new crop was spread to the rest of America,” she says.

Understanding the development of early strains of corn can help us understand the crop as we know it today, says Wales. “Similarly to how the study of Neanderthal genes in recent years has given us important knowledge on people, and highlighted genes that could be important to understand human health today.”

The study is published in the scientific journal, Current Biology.

Origins of world’s most important crop was once a total mystery

Today, corn is one of the world’s most important crops and accounts for around one fifth of the world’s calorie intake. It enabled the spread of civilisation in the Americas and is a good example of the way humans have dramatically modified plant species through time.

But until now, the origins of corn was something of a mystery, as the modern strains bear no resemblance to any wild plants alive today. Other crops like apples or wheat have wild varieties that are closely related to their original form, but not corn.

Botanists have long believed that corn’s ancestor died out long ago.

Read More: Ancient crops are the future for our dinner plate

Corn resembles wild grass

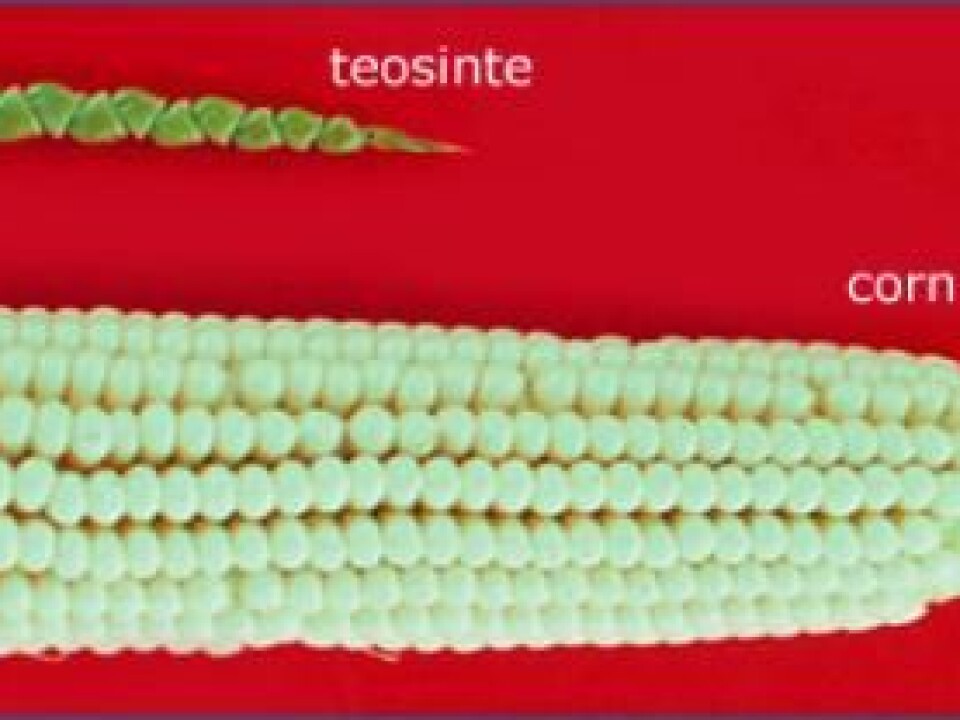

This all changed when geneticist George Beadle discovered that a species of wild grass called teosinte had chromosomes identical to corn.

Beadle suggested that the two plants could produce viable offspring, which meant that they were in fact of the same species, and corn was merely a domesticated version.

There was just one problem: teosinte looked nothing like corn.

But Beadle showed that, genetically, they were quite similar, and only differed in terms of four or five specific genes. So it was plausible that early farmers had used teosinte to breed corn some millennia ago.

A new complex map of fossil corn

The oldest fossil of what is essentially corn on the cob is called Tehuacan162. It is around 5,000 years old and comes from the highlands of central Mexico.

It is much smaller than a present-day corncob, measuring just 16.3 millimetres long and 3.1 millimetres wide.

Genetically speaking, it sits halfway between the first domesticated corn, which occurred around 9,000 years ago, and the type of corn that we eat today.

“It’s really interesting, because it confirms where corn came from and shows that all maize today is descended from this population,” says Wales.

Wales and his colleagues have produced a very complete genome that allows scientists to closely study all of the interesting parts of the genetic material and compare the development of genes that lead to this dramatic transformation.

Read More: Denmark’s first farmers were immigrants

Cornhusks were the first genetic modification

The scientists discovered new insights in a gene called tga1, which is responsible for teosintes’ rock-hard seed casing.

The study shows that the tga1 gene was already in its modern form in the 5,000-year-old corncob. This indicates that the seed casings were one of the first traits to be altered by the genetic modifications that the early farmers made.

This fits well with results from other studies, which identified the tga1 gene as important to the domestication process, says Swarts.

But their results revealed that another gene, zagl1, was still in its original wild version.

This gene influences whether the seeds sit inside the corn ears or drop off when they reach maturity. It is a trait where plants and people have conflicting interests. The plant wants to spread their seeds, but for farmers, it is much easier if the seeds stay attached to the plant.

This gene was one of the first to be modified by domestication practices in other crops, such as barley.

Earlier this year, another team of scientists mapped the genome of a 6,000-year-old barley plant in Israel. In this plant, zagl1 had been selected and the barley looked very similar to what we would expect today.

“Our discovery shows that the domestication process can be very different in different species. While barley was selected very quickly, we see that the processes used in corn took much longer and followed a more complex route,” says Wales.

Mayans did not depend entirely on corn

It suggests that people’s use of corn in Central America was quite different to the use of wheat in the Middle East.

The scientists suggest that the slow domestication processes shows that the early hunter gatherers were not dependant on corn in the same way that Middle Eastern hunter-gatherers depended on wheat.

“Central Americans collected wild plants on the side of hunting wild animals and perhaps they based their lives on corn for part of the year or as an emergency supply,” says Wales.

Read More: First Scandinavian farmers were far more advanced than we thought

Did corn begin as popcorn?

There are still many mysteries surrounding the domestication of corn and how it spread around the world.

And there is one particularly puzzling piece of the story: why did people start eating the hard-shelled teosinte plant in the first place?

“When I look at pictures of teosinte, I think ‘why on earth would anyone want to eat that?’ That question keeps me awake at night,” says Wales.

The answer could be very simple: they made popcorn.

Beadle even tested this theory, and yes, burnt teosinte kernels do indeed taste of popcorn.

So who knows, perhaps corn began as a fun pop-teosinte, which our ancestors enjoyed while huddled around the camp-fire, listening to stories, and gazing at the stars.

------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex