3D-printed organs give insights to complex anatomy

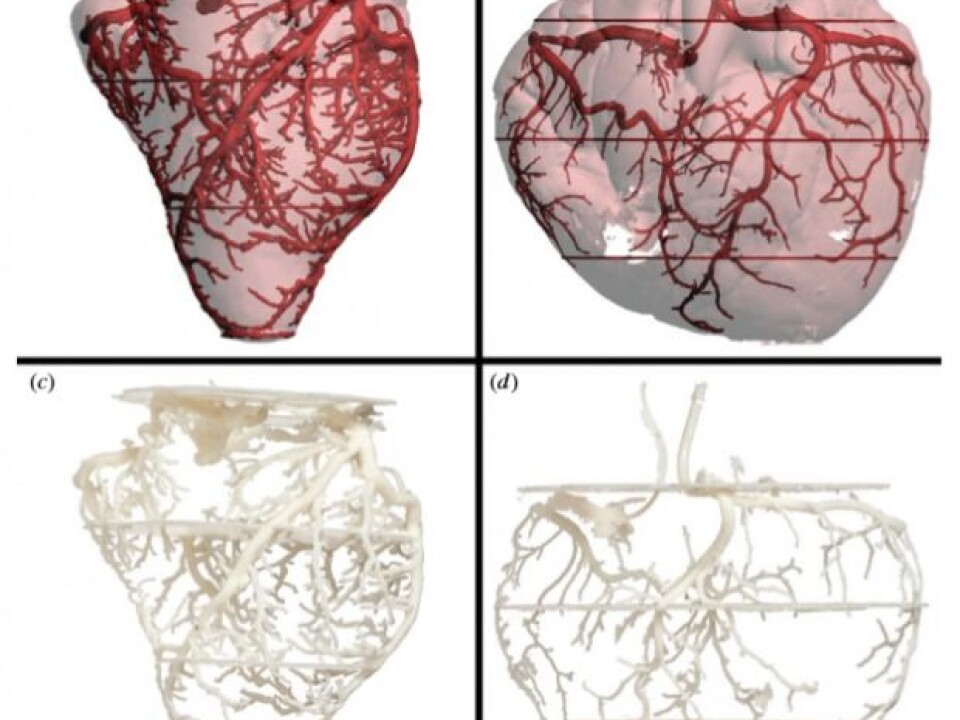

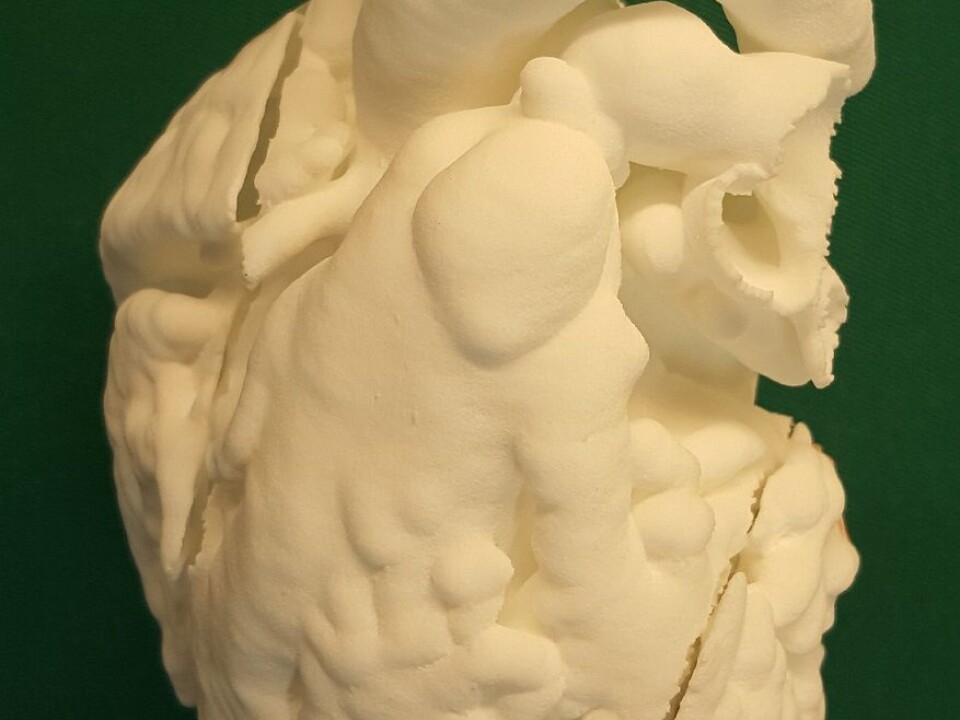

Inexpensive 3D-printers create detailed plastic models of organs and help scientists study complex anatomical structures.

Scientists have shown just how easy it is to print detailed anatomical models using an inexpensive 3D-printer.

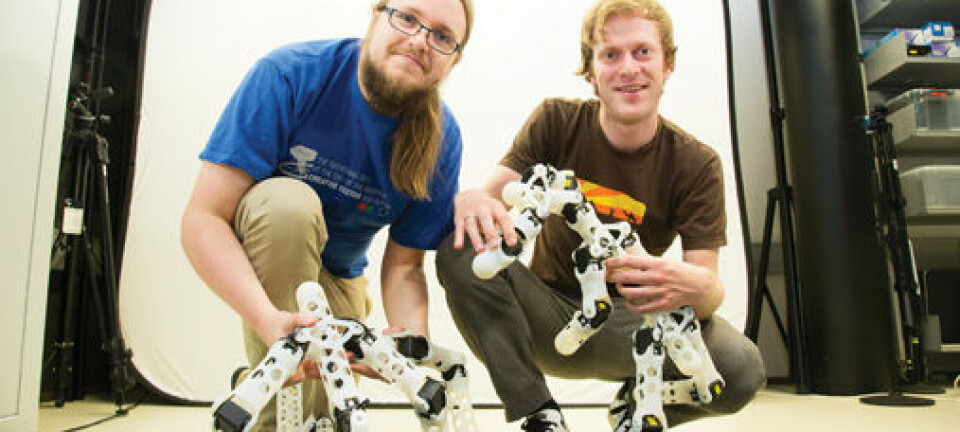

Scientists have scanned 20 different animals using various scanning methods and printers to produce 3D-models of different animals and organs, including frogs, cod fish, giraffes, and moles.

"It can be difficult to describe a complex anatomical structure of an animal that you’ve never examined before with nothing but a flat piece of paper to work with,” says lead-author Henrik Lauridsen, assistant professor in the Department of Clinical Medicine at Aarhus University, Denmark.

“Being able to translate that into a 3D-structure makes it much easier to study the anatomy," says Lauridsen.

The new results are published in the Royal Society Open Science journal.

3D-models make it easy to study anatomy

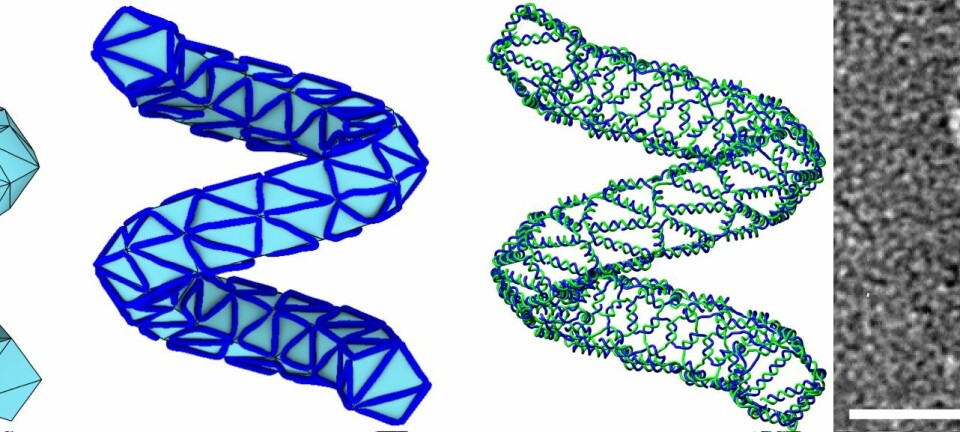

3D-printing has many advantages. In particular, it can help scientists understand complex, small structures.

Models can be scaled up if needed. For example, a tiny insect can be printed ten times its actual size.

Scientists can even attach a file of a 3D-model to their scientific articles for other scientists to either view on the computer or print themselves.

Scientists should not be afraid to try new techniques

Many scientists studying physiology and comparative anatomy have traditionally relied on dissection and microscopy to describe animal anatomical structures. And it can be difficult to move from this to a more technical 3D-print of an organ, which is why this study is particularly useful, says Lauridsen.

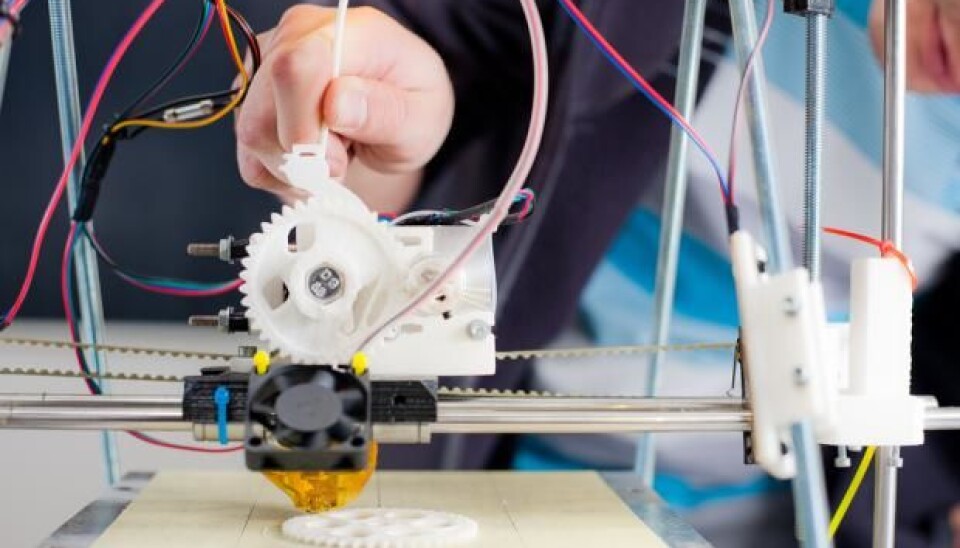

Many scientists might not even be aware that 3D-printers have become increasingly available and inexpensive in the last five years, which may also explain why some have been slow to adopt this new method, he says.

"The interest is there. They [scientists] just need to stop being so afraid and dive in," says Lauridsen.

David Pedersen studies 3D-printing at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU). He was not involved in the new study, but agrees that many scientists are put off when they have to learn new techniques.

There is a big difference between the cheap and the more expensive printers in terms of usability, says Pedersen.

"The market is a bit of a jungle, as there is a big gap between 3D-printing as a hobby and industrial 3D-printing,” says Pedersen, citing the costly procedure of accurately reproducing veins, tissue structures and texture using a CT scanner.

“If scientists just want a rough model, then inexpensive methods with smartphone pictures are [easily available]," he says.

Print a ping-pong ball in half an hour

According to Pedersen, there is nothing standing in the way of scientists using 3D-printers, they just need to be motivated.

"Most are able to familiarise themselves with how 3D-printing works. First years students here at DTU can use a standard 3D-printer after a few days [training]," he says.

The question is how long it takes to print an organ as long print times could discourage scientists from trying the new method. But small objects are relatively quick to produce, he says.

"Each print takes about eight minutes per. cubic centimetre. The volume increases by a factor of eight--that is, it takes eight times as long to print when we scale something up to twice its size. A ping-pong ball will take about half an hour to print. A litre of milk may take a few hours," says Pedersen.

Pedersen expects more scientists to start using 3D-printers

"In five years’ time, more [research] areas will be aware of what 3D-printers can do,” says Pedersen. It’s just a matter of time before people get over their fear of this new technology and learn how to use it, he says.

Video: Scientists from Aarhus University, Denmark, demonstrate the accurate models of internal organs produced with a 3D-printer. Here you see a model of a fossil dinosaur’s femur. The model reproduces the texture, shape, and colour. (Video: Aarhus University)

---------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex