Scientists map the earliest Icelandic genome

Scientists have mapped genetic material from the first generations of Icelanders, whose DNA appears to be more closely matched to present day Norwegians than their Icelandic descendants.

Around 870 CE, Norsemen crossed the North Atlantic to reach Iceland, which they spent the next five decades colonising.

Today, 1,100 years later, an international team of scientists have mapped the genetic material of these first generation Icelanders and they can now see how the Icelandic population has changed between then and now.

“You’re looking at the creation of the population,” says geneticist Tom Gilbert from the Natural History Museum of Denmark at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. He is one of the co-authors of the new study published in Science.

The genetic material gives an insight into both the evolutionary mechanisms operating in a small, isolated population, as well as the history of the original population.

”It’s a really interesting study that confirms what we already know from historical sources, but also adds something new to the picture,” says Matthew Driscoll, an expert in Icelandic language and literature at the Arnamagnaean Institute at the University of Copenhagen. Driscoll was not involved with the study.

Professor Mikkel Heide Schierup from the Department of Bioinformatics at Aarhus University, Denmark, is also enthusiastic about the study.

“Iceland’s history is fascinating and here we have direct evidence of how the original population were and what has happened since,” says Schierup, who was also not involved in the study.

Read More: See where the Vikings travelled

Genomes of the first Icelanders

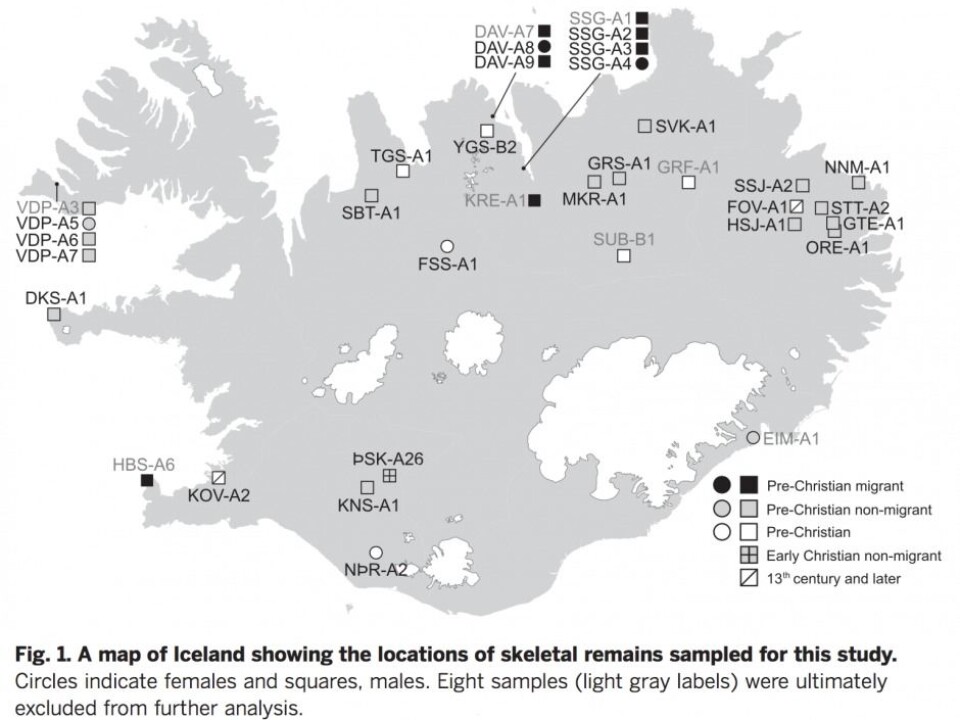

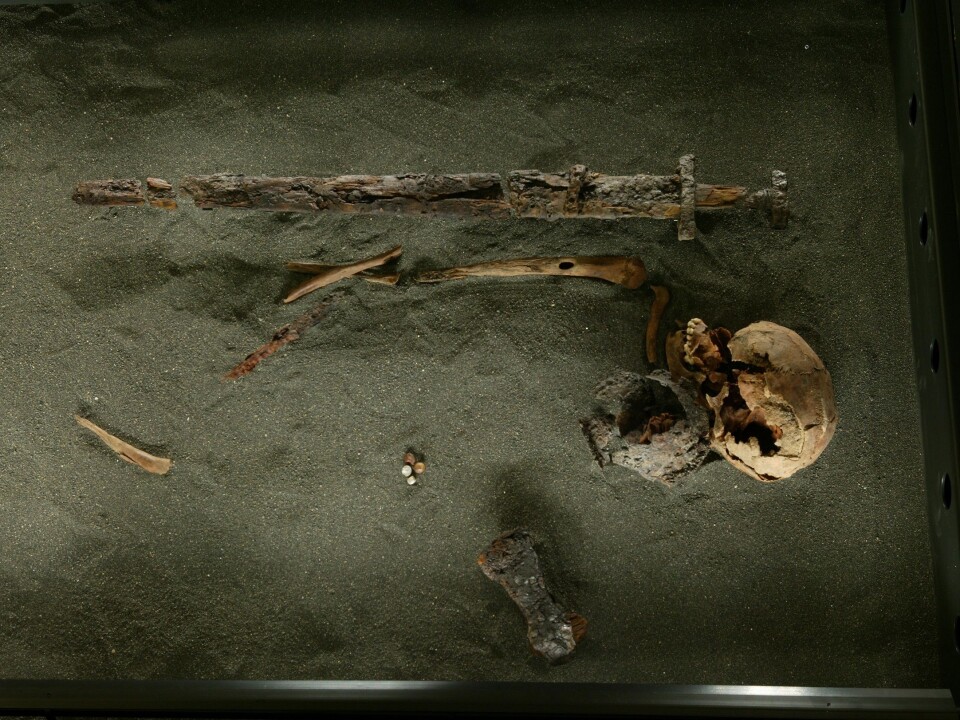

Scientists have now successfully mapped whole genomes from 27 Icelandic skeletons, which were discovered in previous archaeological excavations.

Most of the skeletons date to the Viking Age, more than 1,000 years ago, and are considered to be from the first one to three generations of Icelanders.

The genetics reveal that the first migrants were either Norse (from Norway or Sweden) or Gaelic (either Ireland or Scotland), or a mixture of the two.

This fits with what researchers already knew: That the first Icelanders were Vikings, who brought slaves from the British Isles.

Read More: The Viking Age should be called the Steel Age

Genetics add nuance to Iceland’s history

“It’s interesting that one of the earliest Icelandic genomes was already a mixture of Norse and Gaelic DNA, which indicates that people were mixing before they arrived in Iceland, perhaps related to the Viking settlements in Ireland and Scotland,” says Driscoll.

The Vikings occupied Scotland and Ireland from the end of the 700s CE.

One of the skeletons is a woman with Nordic genes, which shows that Norwegian women must have been among the early migrants.

Read More: Guide to the classics: the Icelandic saga

First Icelanders are more like Norwegians than present day Icelanders

If you thought that Icelanders were the closest people, genetically speaking, to the original Vikings, then think again.

Comparing the early Icelandic genomes with those of present day populations revealed an interesting picture.

Surprisingly enough, people living in Iceland today are not the closest genetic match to the early Icelandic skeletons. Instead, the closest match was among people living in areas from where the colonists originated: Norway, Ireland, and Scotland.

Despite the constant migrations to Norway and the British Isles over the past 1,000 years, it is these populations that have preserved more of the original genes than people in Iceland.

Icelandic genomes, meanwhile, have changed markedly.

Read More: New study reignites debate over Viking settlements in England

Study based on genealogy, health registers, and genetic analyses

The study was led by scientists at the Icelandic genetic research centre, deCODE Genetics, who have access to Icelandic genealogy, health registers, and genetic material.

Today, deCODE is owned by the US biotech company, Amgen, with the view to create commercial products, such as new medicines.

“This is why deCODE are interested in ancient genomes—it gives them a starting point for their work with modern day populations and disease,” says Gilbert.

----------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article at Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex