This is what Alzheimer’s looks like

Swedish researchers seem to have proved that brain scans really can reveal Alzheimer’s disease.

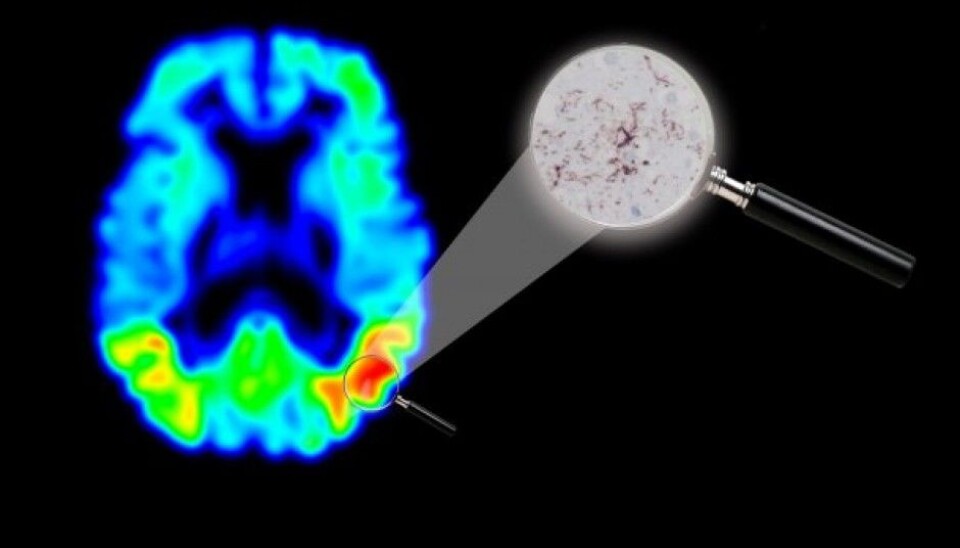

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans of concentrations of the protein tau in the brain are a promising method for imaging Alzheimer’s disease.

But is it really Alzheimer’s we see in the picture?

Yes, it definitely is, conclude a group of researchers at Lund University in Sweden and Skåne University Hospital. They are certain because after comparing images of an Alzheimer’s patient taken with the new method to an actual examination of the man’s brain post-mortem.

Showing the effect of medications

The tau protein does an important job for us. It transports various necessary substances to our brain cells. But Alzheimer’s patients have elevated levels of the protein in their brain cells, which can cause the cells to degenerate and die.

“Tau-PET can improve diagnostics, and moreover the imaging technique can have a great impact on the development of medications against Alzheimer’s disease,” says Ruben Smith, a researcher at Lund University, in a press release.

New drugs have already been developed which scientists think can reduce the accumulation of tau in the brain. The new imaging regime will enable medical researchers studying dementia to see closely how such drugs work on the brains of living patients.

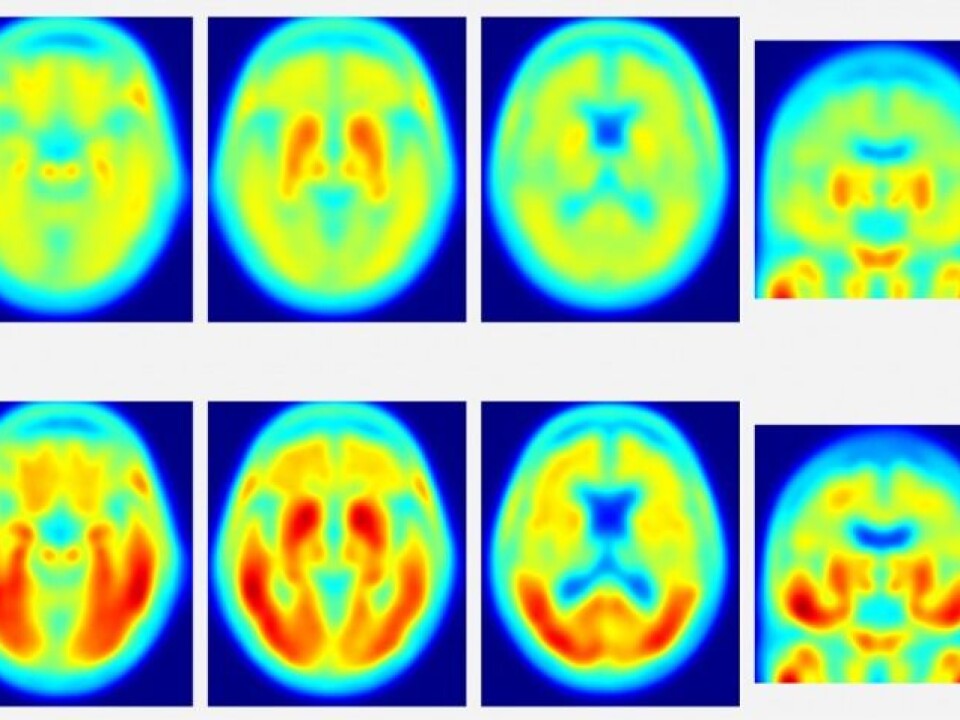

Consecutive Tau PET scans can compare how effective the drugs are.

Just one person

This study is only based on a single person.

“That can sound like very little to base a study on – just one case. But as in the same brain there are areas with concentrations of tau and areas with less tau, images from a single person are sufficient for claiming that the imaging technique works,” asserts Oskar Hansson, another researcher at Lund University.

Answering a mystery

International dementia researchers have debated whether the protein ß-amyloid or the protein tau is the primary culprit to look for when diagnosing Alzheimer’s. You can read more about this discussion in this article in the magazine Science.

PET scans have shown that Alzheimer’s patients have much more ß-amyloid plaque in their brains than healthy persons.

But researchers have to solve a mystery: Autopsies have shown that round 30 percent of people who never suffered dementia had brains full of ß-amyloid when they died.

This has made scientists query as to whether the tau protein is the culprit – if it is what makes brains stop functioning properly and memories to fade.

Or perhaps it is just an accomplice.

Both proteins

Maybe the accumulation of ß-amyloid and tau together is what leads to the dramatic deterioration of a brain stricken by Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia?

According to the magazine Science, neurologist Beau Ances at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, suggests that the brain has ways of compensating for the deficits caused by the ß-amyloid protein. But once tau starts to spread, “that pushes you over.”

Large longitudinal studies of the accumulation of the ß-amyloid and tau proteins are now underway.

Dementia researchers hope that in a few years a simple brain scan will be able to tell doctors what sort of treatment is needed if patients start developing Alzheimer’s disease or some other form of dementia.

--------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Scientific links

- Ruben Smith et al.: “18F-AV-1451 tau PET imaging correlates strongly with tau neuropathology in MAPT mutation carriers”, Brain, Oxford University Press, 29 June 2016

- Underwood, E. “Tau protein—not amyloid—may be key driver of Alzheimer’s symptoms”, Science 11 May 2016