Counter coeliac disease with early glutens

Let your baby taste a little food containing glutens from the age of four months, but continue to breastfeed. This is the advice of researchers who have investigated the remarkable coeliac epidemic in Sweden.

In the mid-1980s something odd occurred in Scandinavia. Paediatricians throughout Sweden started reporting a great increase in babies and toddlers with coeliac disease.

People with coeliac disease need to stay away from food containing the protein gluten, which is found in wheat, rye and barley, because it causes an inflammatory reaction in the intestines. The disease can involve an array of symptoms and many are unaware that they have it.

Medical researchers estimate that about one percent of the world’s population is afflicted.

But in the period from 1984 to 1996, something remarkable happened in Sweden: the number of registered cases of coeliac disease in children under the age of two suddenly quadrupled. After 1996, occurrences sank back again.

What caused this strange outbreak?

Misguided advice

Suspicion fell on infant diets. Two years prior to the epidemic, Swedish authorities and nutritionists revised their recommendations for infant feeding − ironically to prevent coeliac disease.

Contact with gluten triggers the disease. So the way the protein was introduced and the age at which this is done appeared to be affecting the developments.

Whereas earlier advice gave the go-ahead to give infants a little gluten-containing food from the age of four months, the new parental guidelines recommended waiting until the child reached six months.

But contrary to the expectations of dieticians, the number of coeliac disease cases started to mount.

What was going on?

Could the new diet be giving infants stronger symptoms, thus making the disease easier to diagnose at an early stage? Or was the share of children with coeliac disease actually on the rise?

Anna Myléus of the University of Umeå, Sweden, and her colleagues have now studied these and other issues linked to the Swedish epidemic. The conclusion is that the change in the infants’ diet really was causing more cases of coeliac disease.

Thus it’s also possible to guard against the disease by introducing gluten in the proper way, Myléus argues in her doctoral thesis.

More cases

She has conducted several studies to ensure that there was a correlation. One was a screening that charted the prevalence of coeliac disease in more than 13,000 twelve-year-olds born during the epidemic period.

It turned out that the number of children afflicted with coeliac disease was distinctly higher in the group born during the epidemic.

This means its total prevalence increased during the epidemic years, not just that it was diagnosed at an earlier age.

Myléus thinks the phenomenon can be partly explained by several independent dietary changes that occurred simultaneously.

Double whammy

In 1982 the advice to parents was changed and they were urged to hold back on gluten until their babies were at least six months.

At the same time the major baby food manufacturers increased the amounts of glutenous flour in their powdered porridges.

As a result, the babies came in contact with gluten later but once they did they were consuming larger amounts. A sudden introduction to gluten appears to increase the risk of developing coeliac disease, according to Myléus.

Breastfeeding can be a key factor. It appears that babies who had been weaned when they were introduced to gluten were more susceptible to coeliac disease.

The average duration of babies’ nursing periods increased from 1984 to 1996. Perhaps this contributed to reducing the number afflicted toward the end of the epidemic.

Genes, gluten and the environment

Changes in diet appear to explain much of the coeliac disease epidemic in Sweden. But other factors were involved too. Previous research indicates three risk factors:

It’s been proven that certain gene variatiants are linked to the disease. About 25 percent of the population has these genes. These people have been in contact with gluten, which actuates the genetic potential.

Yet only a small share of the population develops the disorder, even though many of them both eat gluten and have this genetic disposition. This means that environmental factors are probably involved too.

Infections

One question that arose is whether changes in the Swedish child vaccination programme could have increased risks of coeliac disease. So Myléus checked for an overlap.

But no such link was found.

However, it looks as if early infections can have an impact. Parents of children who developed the disease were more likely to report that their kids had several infections such as colds, ear infections and gastric flu in the first six months of their lives.

These children appear to be more susceptible if they are no longer getting mother’s milk during their first encounter with gluten, and if they were given what could be called overdoses of gluten. So infections are directly involved in the coeliac disease epidemic.

Myléus writes that certain types of infections might have been more common in the years from 1984 to 1996, but insufficient data makes this uncertain.

To sum up what can be deduced:

Infant diets can increase the risk of developing coeliac disease. This means that the risk can be reduced by choosing the right diet.

Myléus argues that there is no scientific basis for saying it’s risky to let babies try a little glutenous food between the age of four to six months.

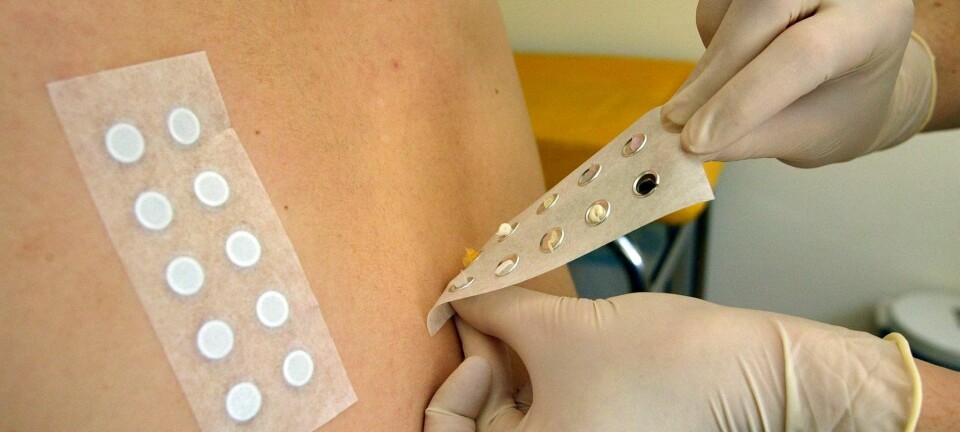

So she and her colleagues advise parents to carefully introduce their babies to a little gluten from the age of four months, preferably while it is also breastfeeding.

-----------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Scientific links

- A. Myléus: Towards Explaining the Swedish Epidemic of Celiac Disease – an epidemiological approach, 2012, Umeå University Medical Dissertations New Series, nr 1506, ISBN 978-91-7459-436-2.

- A. Myléus et al: Early Vaccinations are Not Risk Factors for Celiac Disease, Pediatrics, 2012, vol 130, s 63-70 (abstract)

- A. Myléus et al: Celiac Disease Revealed in 3% of Swedish 12-year-olds Born During an Epidemic, Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 2009, vol 49, s 170-176.