Tiny microplastics a marine headache

Food packaging. Drink bottles. Electronics. Children’s toys. Plastics make modern life possible, but they have a dark side. Plastics in the ocean break down into microscopic fragments that zooplankton not only eat, but pass up the food chain, a Finnish research team has shown.

It takes a lot of plastic to make the Western world work: an estimated 280 million tonnes of plastics are produced annually to make everything from the yoghurt container in your refrigerator to the plastic bag you used to tote it home.

As much as 10 percent of these plastics end up in the world’s oceans, littering beaches in even the remotest places on the planet and killing birds and animals that mistakenly ingest the junk, thinking it is food.

But scientists are increasingly concerned about an aspect of plastic pollution that isn’t as easy to see, because of its size. Microplastics, or tiny pieces of plastic less than 5 mm in diameter, are created when bigger bits of plastic are broken down by waves or degraded by the sun.

While the breakdown of big plastic junk into invisible bits sounds like it would be a good thing, it’s not. In the February 2014 edition of Environmental Pollution, a team of Finnish researchers documents for the first time that microplastics can be passed up the marine food chain by zooplankton.

Hitchhiker pollutants

Outi Setälä, the first author of the study and a senior researcher at the Finnish Environment Institute, says that scientists have known since the 1980s that zooplankton will eat microplastics.

Scientists have also suspected that plastics could be transferred up the food chain, but until her study, no one had actually done the experiment to see if it in fact happened.

“We know that animals eat each other, and that they also eat the stuff that is inside each other,” she said. “Now we have a study that shows that these particles can potentially be transferred up the food web.”

No one expects that zooplankton will die of starvation by filling their stomachs with microplastics, though.

But tiny bits of plastics contain chemical additives that are a result of their manufacture. They also tend to be a magnet for a range of organic pollutants, including PCBs and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

That means that microplastics could act as carriers for the pollutants, and provide yet another avenue for contaminants to enter the marine food chain.

Fluorescent microspheres

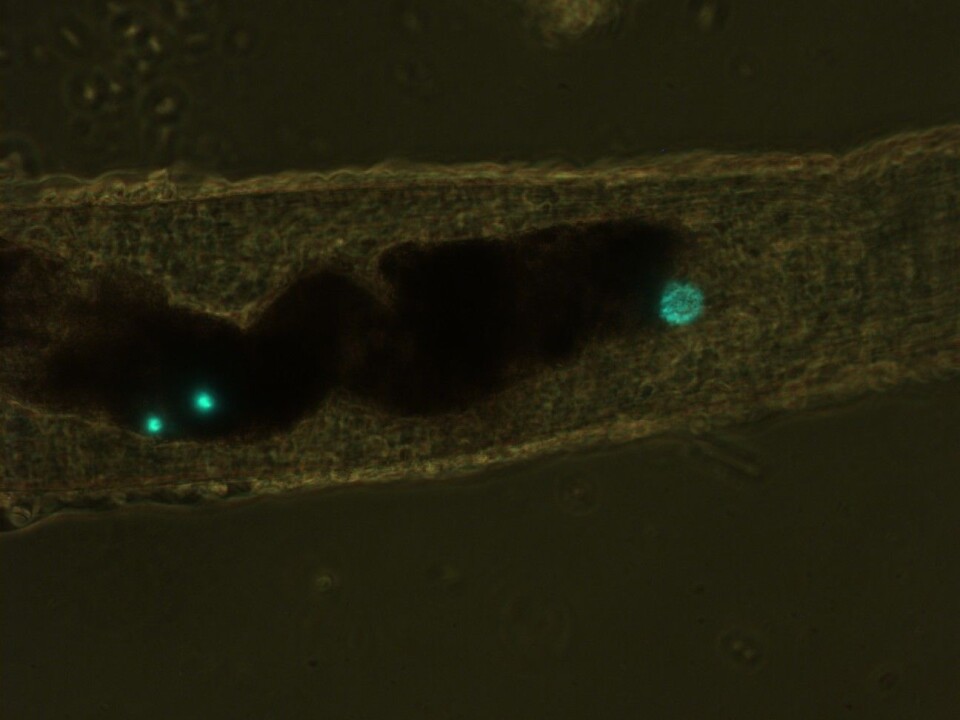

Setälä and her colleagues used 10-micrometre (µm) fluorescent polystyrene microspheres, which were roughly the same size as some of the food particles that tiny zooplankton, such as copepods and polychaete larvae, eat.

The researchers put zooplankton that they had caught in the Baltic Sea in flasks with different concentrations of the microspheres, where they saw that many species ate the microspheres.

When the zooplankton that had eaten the microspheres were put in 1 litre flasks with mysid shrimps, which are one step up on the food chain, the researchers were able to document that the mysid shrimps gobbled up the smaller zooplankton – and the microspheres.

Real microplastics aren’t round

Of course, what goes into an organism can also come out. Setälä and her colleagues also saw that the microspheres could pass through the shrimp and many of the copepods.

But she cautions that microplastics in the ocean aren’t as small, round and uniform as the fluorescent microspheres the researchers used.

“In the real world, microplastics are irregularly shaped, and can get stuck inside organisms, and in that way they can accumulate more of the plastics,” she said.

And even though the mysid shrimp were able to pass the microplastics through their stomachs, “if the pieces had been bigger, they might get stuck,” she added.

Microplastics everywhere

Richard C. Thompson is a professor of marine biology at Plymouth University in the UK who has conducted some of the pioneering studies on microplastics in the marine environment.

In 2004, for example, he published an article in Science magazine documenting the presence of microplastics at 18 beaches around the UK; scientists have subsequently documented the presence of microplastics worldwide, in the water column and at beaches.

And by examining zooplankton samples that had been archived from the 1960s that were collected in the North Atlantic, Thompson and his colleagues were able to see that microplastics were around even then.

“The surprise (in 2004) was the ubiquity,” he said.

Understanding the risks

Now, he says, scientists have to pursue two different lines of research to understand the risks these microscopic plastics pose.

One is to see if the plastics can cause physical harm – whether tiny bits of plastics could clog digestive systems, much like larger pieces of plastics fill the bellies of birds and mammals that ingest them.

Many microplastics are not round, as Setälä noted, but fibrous.

One of Thompson’s studies from 2011 found that washing machine wastewater and other sewage may be an important source of microplastic fibres, with a single garment made of polyester or acrylic fabric capable of producing more than 1900 fibres per wash.

The second is to examine the toxicological risks that the plastics pose, whether from the chemicals they contain or those that stick to the plastics. The evidence is beginning to come in, Thompson said.

At least one recent study, authored by one of Thompson’s former graduate students and colleagues, including Thompson, showed that a type of filter feeder called a lugworm was adversely affected when exposed to sand that had microplastics that contained common chemical pollutants.

There is no ‘away’

Thompson emphasizes that these findings are a cause for concern, but not alarm, especially when it comes to human exposure.

Nevertheless, he says that the ubiquity of microplastics should be a wake-up call for society to push harder to recycle plastics and to reduce the problem of plastic litter overall. An estimated 80 percent of marine litter comes from the land, according to the United Nation’s Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP).

Trash is either blown directly into the ocean by the wind or carried by stormwater runoff, which sweeps debris from city streets and dumps it into the ocean via sewage outfalls.

“We have been taught to live in a disposable society, and plastics have no value,” he said. “But we are beginning to realize that there is no ‘away’, and that we have to design things that can be recycled at the end of their life.”