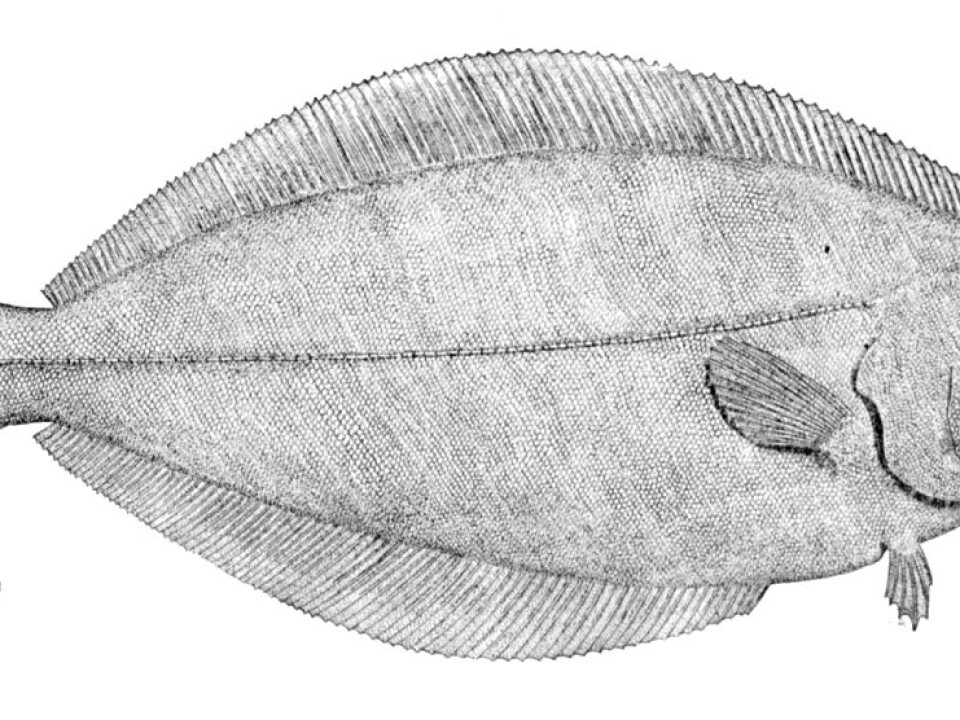

Halibut pierced by mysterious ’projectile parasite’

Researchers have discovered a previously unknown parasite that attacks the Greenland halibut by piercing the fillet. The fish almost looks as if it were shot with a rifle.

The halibut is a popular delicacy among seafood lovers. But perhaps the pretty slices and the fine texture of this fish shouldn’t be taken for granted in the future.

During filleting work, Greenlandic fishermen recently noticed that a specimen of Greenland halibut was full of strange cavities and holes that resemble shot wounds.

The mysteriously infected fish was sent to the Laboratory of Aquatic Pathobiology at the University of Copenhagen, where researchers examined the holes in detail.

They discovered that the Greenland halibut had been infected with a hitherto unknown parasite, which creates circular holes in the fish muscle.

“At first glance it was impossible to see why the holes had appeared,” says Professor Kurt Buchmann, of the Laboratory of Aquatic Pathobiology at the Department of Veterinary Pathobiology at the University of Copenhagen, who headed the study.

“But when I took a closer look through a microscope, I could see that the holes actually consisted of cartilage containing millions of tiny parasites of a previously unknown type.”

Holes go straight through the flesh

According to the professor, the holes emerged as a result of the parasites attacking cartilage elements in the fish’s skeleton.

The cartilage reacts to the infection by swelling dramatically and transforming into long, circular cylinders that go straight through the fish’s musculature and make it appear riddled.

The researchers have subsequently nicknamed the parasite ‘the projectile parasite’.

“The cylinders go all the way through the fish, equivalent to, for example, a bone passing all the way through the arm or the thigh of a human,” explains Buchmann.

“This does not cause the fish to die immediately, but it probably faces an impoverished life and its body becomes very stiff.”

Parasite is several million years old

The parasite has not been described before, neither by fish researchers nor parasite researchers. But its shape reveals that it is of the type Myxobulus – a parasite that’s characterised by being very small and rounded.

Since Myxobulus hasn’t previously been observed in the halibut, the researchers knew they were dealing with a new species within Myxobulus.

“Detailed DNA analyses also revealed that the newly-discovered projectile parasite was not present in the gene bank for parasites. Moreover, it differed greatly from other known types of parasites.”

Although the projectile parasite has hitherto been completely unknown, it is not a newcomer.

”It has probably existed for millions of years – it’s just not been discovered by scientists until now.”

No threat to humans

Although the parasite makes the delicate fish flesh appear a bit less appetising, Buchmann stresses that it poses no threats to humans.

“If we disregard the fact that the parasite may cause grief for fishermen and the industry through revenue losses, the parasite cannot infect humans at all,” he says, adding that this type of parasite can only infect low-ranking animals.

Epidemic is unlikely

The researchers still know very little about this parasite and how it spreads. Nevertheless, Buchmann doesn’t believe the parasite should give rise to fears that the Greenland halibut – or any other fish – are facing a contagious epidemic.

“I certainly hope not,” he says. “Of course, we cannot say with certainty that the parasite isn’t capable of infecting other fish. We do know, however, that many parasites for some reason prefer specific types of fish.”

Further tests are required before it can be determined more precisely how prevalent the parasite is.

“The Greenland halibut occurs in a fairly large area in the North Atlantic, from northern Norway to the Pacific. So it is not inconceivable that halibut in various locations around the world carry the parasite. But so far it doesn’t appear that the halibut is facing an alarming disaster.”

And seafood fans shouldn’t worry that the holes in the fish affects its delicate flavor:

“This is just the fish world’s version of the Swiss cheese. So you can safely go ahead and eat around the holes,” says Kurt Buchmann.

-------------------------------

Read this story in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther