Your genes decide how old you get

New study reveals that small molecular differences in your genes decide whether you’ll live to be 60 or 100.

If your grandparents were able to celebrate their 90th birthday there’s a good chance you might do the same.

Our age is determined partly by our genes – not only how long we live, but also how we well we are, physically and psychologically.

That some people become really old while others don’t even reach pension age is determined partly by inherited molecular variations in the DNA code in our genes.

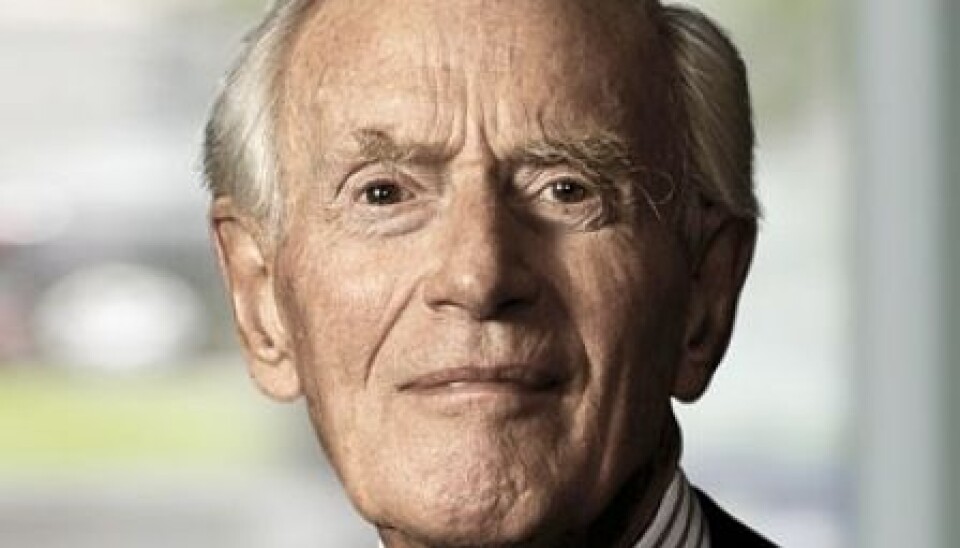

A Danish researcher has now studied the genetic variations that make people live longer.

“The study shows that small variations in our genetic code give large differences in how long we live and in the quality of our old age,” says Mette Sørensen, of the epidemiology research unit of the Institute of Public Health at the University of Southern Denmark, who has just defended her PhD thesis on the importance of genetic processes for the length of our lives.

Studied three vital processes

Sørensen studied variations in the genes behind three of the body’s systems that influence the length of our lives:

- Our cells’ defence against ‘free radicals’. Antioxidants are the body’s defence against the damaging molecules known as free radicals. If they are allowed to circulate freely in the body’s cells, free radicals can bind to and damage a large number of the cells’ proteins and DNA. Antioxidants change the free radicals, so they can no longer damage the functional parts of our cells.

- DNA repairs. The biochemical processes that repair the cells’ DNA are of great importance to the body’s potential age. Our DNA is damaged constantly by factors such as sunlight, chemicals and by errors that arise when the DNA divides into two new cells. If our DNA is not repaired correctly, the damage will accumulate in the cells and lead to the development of cancer or other diseases.

- Insulin signalling. Insulin has great influence on the body’s ability to use energy and grow. Several researchers have suggested that elderly people can live longer if they consume fewer calories.

Sørensen studied 168 genes for variations in a control group of middle-aged people and a test group comprising people aged 92 or over.

The result showed that specific variations of 23 genes are more prevalent in the elderly part of the population and can potentially influence the length of their lives.

That a genetic variation is more prevalent in the elderly part of the population than in the population generally is a good indicator of the influence the genetic variation has had for people living longer.

Variant of Foxo3 gene extends life

A variation in the Foxo3 gene is particularly interesting. Foxo3 is part of the collection of genes that control insulin signalling, and specific variations of this gene are very common in people who live a long time.

“We are convinced that the Foxo3 gene has an influence on lengths of peoples’ lives,” says Sørensen.

“People who have Foxo3 genetic variations with an over-representation of a certain nucleotide [see Factbox] live longer than average. We can see that in the genetic material from the test group of people over 92 years old. But we don’t yet know why.”

The researcher underlines that people do not necessarily live longer simply because they have the specific Foxo3 genetic variation – there are far too many other factors that play a role.

Research continues

Although the researchers can see that a specific variation of a gene means we live longer, there is little that can be done today for the people who do not have this genetic variation and are thus at risk of having a shorter life.

But that may change in the future.

With knowledge of the genetic variations that increase the risk of developing diseases – such as cardiovascular diseases or Alzheimer’s disease – that can shorten our lives, or reduce the quality of our lives, doctors in the future can examine patients for such genetic variations and start treating them far earlier.

Sørensen continues her work of generating an overview of the genetic variations in the body’s processes that have influence on how long we live.

She will do this as part of a research group at the University of Southern Denmark. The researchers will also study the whole genome in their hunt for genetic variations that are over-represented in the eldest members of the population and which can potentially determine how old we will be and the quality of our life.

“This isn’t just a matter of getting old, but also of getting old with a good quality of life,” she says. “In many processes it is therefore relevant to study the underlying genetics.”

-------------------------------

Read this story in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Michael de Laine

Scientific links

- ’Human longevity and variation in GH/IGF-1/insulin signaling, DNA damage signaling and repair and pro/antioxidant pathway genes: Cross sectional and longitudinal studies, Experimental Gerontology, doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2012.02.010

- Replication of an Association of Variation in the FOXO3A Gene with Human Longevity Using Both Case-control and Longitudinal Data, Aging Cell, doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00627