Swedish teens now toe the line

The behaviour of Swedish 15-year-olds has improved since the mid-1990s – they're less likely now to skip school, steal or drink than they were in the past.

Swedish researchers have charted the misbehaviour of ninth graders since the mid-1990, while also assessing their attitudes towards various infractions and crimes.

The latest results, gathered in 2011, show that Swedish kids are better behaved than before.

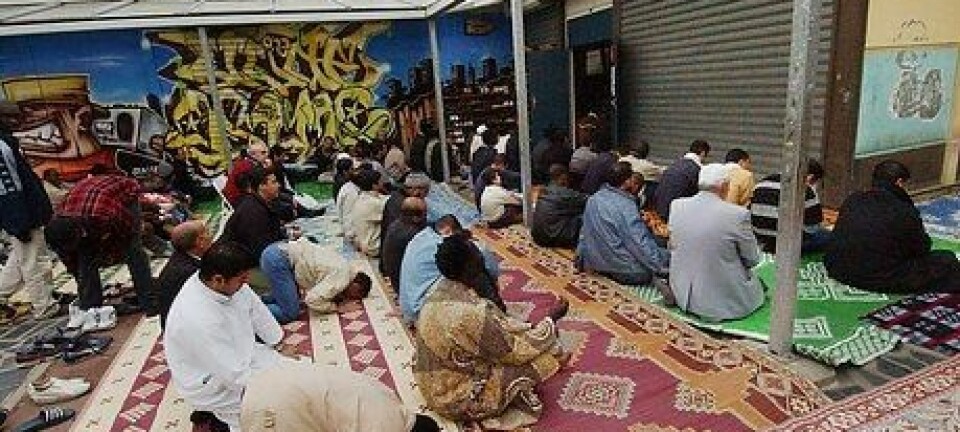

Fewer of them play hooky, scrawl grafitti on buildings or other public structures, steal or get involved in serious crimes such as assaults and burglaries.

Adolescent Swedish boys and girls are also more disapproving of this kind of behaviour – with grafitti, skipping school and shoplifting deemed as less acceptable now than when the researchers began their study in 1995.

Fewer shoplift, drink or tag

Ninth grade is the final year of compulsory schooling in Sweden. Most students are 15 years old that year.

In this anonymous survey, roughly 6,500 of them responded as to whether they had ever engaged in criminal activities or in what could be called problem behaviour, such as playing hooky – also called skipping school.

The researchers also asked the teens about their relationships with their parents, whether they had friends who had broken the law and how much they enjoyed school, along with a host of ot questions. This is the eighth time the survey has been carried out in Sweden.

The ongoing study shows a decrease in nearly all negative attitudes and behaviour.

In 1995 the percentage that admitted to petty thefts or shoplifting was 37 percent, as compared to 18 percent today.

The percentage that had engaged in tagging – or graffiti vandalism – sank from 44 percent to 34 percent. The same percentage had played hooky in the 1995 and the 2011 studies respectively.

Fewer drank alcohol. In 1995 two out of three teens had got drunk at least once, while in 2011 only 43 percent had done so.

The study shows that girls are still more law-abiding than boys, with a few exceptions.

More girls than boys said they had got drunk at least once, for example. The share who had tried drugs was about the same for both sexes.

Criminal minority

The researchers discovered that today's kids are more disapproving of crime. In 2011, far fewer thought it would be okay for a friend to shoplift than when the question was asked in 1995.

A small minority is responsible for most of the delinquent behaviour. Around ten percent of the teens who answered the questionnaire were responsible for two-thirds of the crime.

The researchers wrote that as expected, the teens who had engaged in the most crime more often had a relaxed attitude toward the law. They were more likely than well-behaved teens to have a poor relationship with their parents and spent more time hanging out with friends in the evenings.

The kids with delinquent behaviour had less self-control and were less concerned about succeeding at school – at least according to their responses.

Fewer respond

The Swedish researchers compared their results to similar studies in Finland and Denmark. Although they made no mention of equivalent Norwegian studies, Statistics Norway has a study from 2012 which shows the same trends.

The researchers reported one possible source of error in their work: Fewer and fewer kids answer the questionnaire each time the study is conducted. In 1995 only five percent refrained from responding.

By 2011 that percentage had grown to 22 percent.

The researchers wrote that most of the ninth graders who failed to answer were not at school for one reason or another the day the study was carried out.

This suggests that the percentage of students who actually played hooky could be too low. It seems reasonable to assume that the number who admitted to skipping school would be higher if the kids who were not in school the day the survey was given had also participated.

Nevertheless, the Swedes think the results are generally reliable, in part because the same trends for roughly the same factors were seen in each study.

------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling