An article from The Academy of Finland

Antarctic meteorology

Just as the world economy, the climate is a system where everything ties in with everything else. Changes happening in the Antarctic can be felt on the other side of the planet, says Finnish scientist.

“The melting of glaciers in the southern hemisphere can affect sea levels even here in the Baltic Sea," says Timo Vihma from the Finnish Meteorological Institute.

"This is through a mechanism that changes the distribution of the Earth’s mass, causing slight deviations in the direction of gravitational acceleration,” he explains.

Antarctica is a vast area of some 14 million square kilometres. Almost the entire continent is covered by thick ice, and in the winter sea ice extends all the way to 55 degrees latitude.

The loss of snow and ice in this region impacts the climate globally, because snow cover reflects much more of the incoming shortwave radiation from the Sun than does open water or snowfree land. Reduced reflection, in turn, accelerates climate warming.

The Antarctic climate system is not yet fully understood. Timo Vihma is involved in an international research project called Antarctic Meteorology and its Interaction with the Cryosphere and Ocean, which is aimed at increasing our understanding of the interactions taking place between the atmosphere, ice and oceans.

The research provides the foundation for the modelling of interaction phenomena, and it will also contribute to the development of weather forecast and climate models.

Timo Vihma is a meteorologist, but he has a strong background in marine research. He has been studying the dynamics of sea ice and the interactions between the ocean and the atmosphere since the 1990s.

Towards a better understanding of climate mechanisms

Recently, scientists have focused their attention on low pressures, the atmospheric boundary layer and snow-covered surfaces and solar radiation in the Antarctic.

In particular, studies have aimed to investigate the interactions between large-scale atmospheric pressures fields and low pressures, and to determine how heat transfer from the sea affects the rotation of the ocean.

“Research into Antarctic low pressures is extremely interesting. Large low pressure areas tend to control the state of sea ice, surface water temperatures and heat exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean. Smaller low pressures, then, are exposed to the effects of ocean and sea ice surface temperatures,” says Vihma.

Scientists have also been working to explore the mixing of air masses in the lowest atmosphere and its effect on the temperature, humidity and winds. One area of special research interest is katabatic winds or drainage winds.

Drainage winds are created when the snow cover surface in the upper part of a glacial slope cools and the very cold layer of air that is formed on the surface flows down the slope under gravity. Timo Vihma says that drainage winds have the simultaneous effect of cooling and warming the atmosphere.

“Drainage winds bring cold air from the interior of the continent to coastal regions, but, on the other hand, they also cause increased mixing of air in the lowest atmospheric layers. In this mixing process, warmer air is captured from upper atmospheric layers, warming the air masses nearer to the surface," explains the researcher.

"Whether the net effect is cooling or warming depends largely on the gradient of the slope and altitude differences. Drainage winds also have a major impact on the ocean and sea ice, as well as on heat transfer from the ocean to the atmosphere.”

Other research interests include the structure of snow, thermodynamics, solar radiation as well as the reflection of solar radiation from the snow. Solar reflection from the snow is considered one of the most important factors impacting climate change in polar regions.

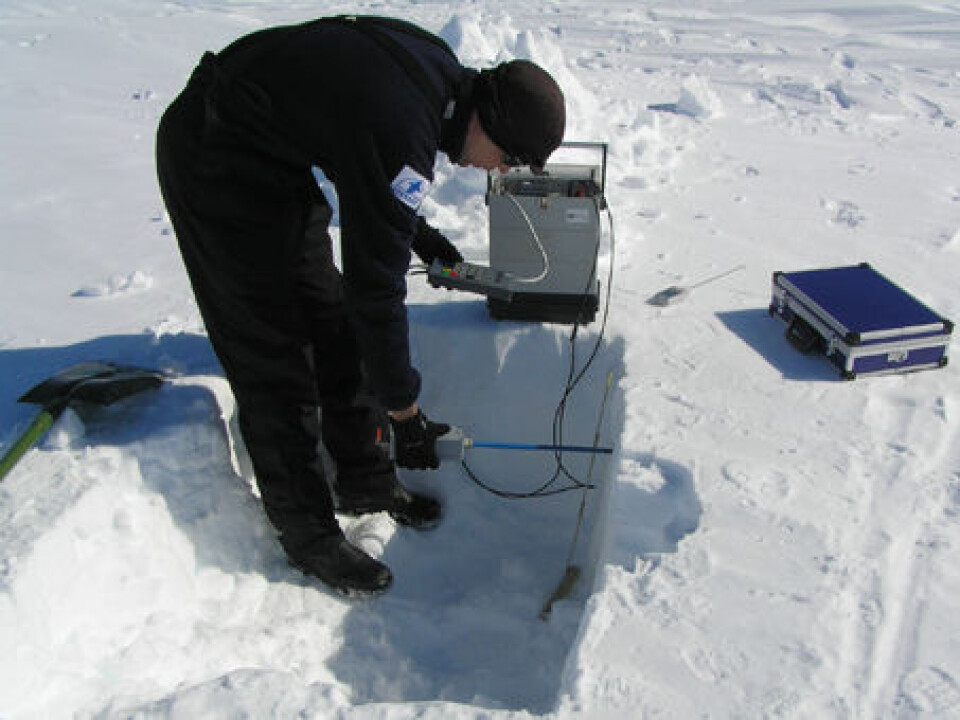

Measurements of snow density and temperature being taken near the Aboa research station.

One source of confusion for scientists is that they have seen no decrease in the amount of sea ice in the Antarctic, in sharp contrast to what is happening in the Arctic region in the northern hemisphere. The Arctic sea ice is melting at alarming speed, but in the southern hemisphere the Antarctic sea ice is in fact expanding.

“The mechanisms are highly complicated, and they have to do with the heat exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean and with the dynamics of ice.”

Scientists have also analysed climate change time series which show that over the past 50 years, there have been no increasing trends in Antarctic precipitation.

“However, I believe that as human-induced climate warming progresses and its effects begin to exceed natural variation, then we’re certainly going to see an increase in precipitation levels,” concludes Vihma.