An article from Aarhus University

A sex life with rape and pepper spray

Bed bugs have some rather special sexual habits involving rape and pepper spray.

Bed bugs are blood-sucking insects and one species in particular, the common bed bug, has adapted to a life together with humans.

Anyone who’s had bed bugs in their home knows how annoying they can be when they come out at night and suck blood out of you while you’re sleeping.

The bites can resemble mosquito bites, but luckily these insects are not believed to be able to transmit diseases. Yet the mere thought of having these little parasites in one’s bed is enough to make most of us shiver.

And most of us don’t even know about some of the perverted action going on between these little bugs while we’re peacefully at sleep.

They have a highly unusual mating behaviour in which the male almost rapes the female.

Traumatic insemination

If a male bed bug meets a female and he fancies his chances, he quickly climbs up on her back and latches onto it.

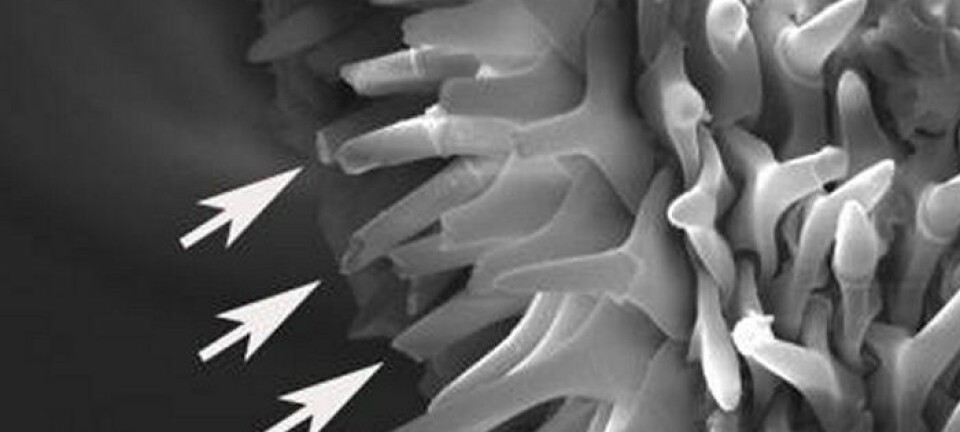

He then wraps his abdomen around the female and tries to pierce his awl-shaped sex organ (see picture 2) in through the cuticle on the underside of her abdomen. If successful, he will inject his sperm through the resulting wound into the female’s abdominal cavity.

So the intercourse does not take place through a reproductive tract, as is the case with most other insects and animals in general, but directly through the cuticle. This has become known as traumatic insemination, as the act causes real physical injury to the female bed bug.

The special inner structure of the female bed bug

Such an extreme mating behaviour would be unlikely to survive through evolution if it caused such great injury to the female. It actually turns out that the female physiology has adapted so that the injury is reduced.

Her cuticle has a certain shape that guides the male sex organ to a specific location on the underside of the abdomen (the ectospermalege, see picture 3). Here the female has developed a special inner structure, which can collect the sperm and from which the seed is free to travel through the body cavity to the ovaries where the eggs are fertilised.

Sexual competition

Despite these evolutionary adaptations, traumatic insemination is still harmful to the recipient, and females who receive many matings have been shown to have a shorter lifespan than those who only receive few.

So there is a basis for a form of sexual conflict in which there is an evolutionary advantage for the male to have mate with as many females as possible, whereas the female should avoid receiving too many matings.

Fatal homosexual inseminations

Other males can suffer even more than the females, because the male bed bug will attack other males or even large nymphs (the bed bug life cycle goes from egg to nymph, progressing through five nymphal stages to adulthood), especially if they meet just after having sucked blood.

If a male successfully inseminates another male (or a nymph), these will die after a short while. This is probably because they lack the same physiological adaptations that the females have.

Pepper spray protection

As the male bed bug cannot survive homosexual mating attempts, it’s no surprise that it has developed a defence system, the function of which most of all resembles pepper spray.

Through glands on the underside of the thorax, they can emit defensive compounds that can fight off the attacking male.

The function of these glands has been demonstrated by showing that males who have their ‘defence glands’ blocked in the laboratory are more vulnerable to homosexual mating attempts and die faster than normal males.

It’s also been known for several years that the female bed bug tries to avoid copulation attempts by positioning herself in a way that leaves the male unable to reach her ectospermalege on the underside of the abdomen.

Furthermore, scientists also know that the females sometimes release volatile chemicals, but this was not thought to have any effect on the males’ copulation attempts.

Volatile chemicals visible on video

In a study, just published in the renowned science journal PLOS ONE, we have examined the bed bug’s use of volatile chemicals by combining new methods of chemical analysis (Proton Transfer Reaction – Mass Spectrometry or PTR-MS) with video recordings.

With PTR-MS, scientists can carry out continuous analyses of ambient concentrations of chemical substances. Previously they had to collect air samples over a period and then analyse the samples.

This difference means that with the PTR-MS readings, we always knew which substances were present.

By combining these readings with video recordings of the bed bugs’ behaviour, we could relate the emitted substances to specific behavioural patterns.

Greatest activity after sucking blood

In the study, small groups of bed bugs were placed in a see-through cubicle and were given the chance to suck blood.

The bed bugs are particularly active in their mating after having sucked blood. This may be because the swollen abdomen of the blood-filled female makes it harder for her to defend against copulation attempts from males.

The air in the cubicle was measured with the PTR-MS system throughout the process while the behaviour of the bed bugs was recorded on video.

This enabled us to identify heterosexual and homosexual copulation attempts and relate them to which volatile chemical substances were measured in the air.

No difference between male and female defence substances

Our results showed clearly that two defence substances, hexenal and octenal, are excreted in large quantities in some very sudden and short-lived releases, which always coincided with the interruption of a copulation attempt.

In this context it made no difference whether it was a homosexual or a heterosexual copulation attempt.

We did, however observe significantly more releases of defence substances in homosexual copulation attempts, possibly because it’s more important for males to avoid being inseminated.

An analysis of the relationship between the two substances revealed great variation, but no significant differences were observed in the ratio or the amount of the two components released from males or females.

This suggests that the exact composition of the defence substances does not affect their function.

Females need to preserve their energy

So the female bed bug is better at defending herself than previously thought, since in addition to blocking the male from reaching the ectospermalege, she can also prevent copulation attempts by excreting defence substances like males and nymphs do.

Our study also showed, however, that the female did not block all copulation attempts: we observed heterosexual mating sessions carried through without any volatile chemicals being excreted.

The findings therefore prepare the ground for further behavioural studies of bed bugs to determine how the female’s ability to defend herself against unwanted mating attempts affects the sexual conflict between males and females.

One could imagine that there is a significant difference in the use of defence substances depending on whether or not the female has previously mated, since she needs to mate at least once in order to lay eggs.

Another important aspect is that it’s obviously quite costly for the female to excrete large amounts of defence substances, so perhaps they need to ‘hold their fire’.

In relation to other animals, this study has also demonstrated that the combination of PTR-MS and video is very useful in many situations where volatile chemicals are excreted, and when scientists want to link this excretion to specific behavioural patterns.

---------------------------------

Ole Kilpinen is a senior researcher at the Institute of Agroecology, Aarhus University, working on physiology, behaviour, and control of ectoparasites on humans and domestic animals.

---------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther