Researchers' Zone:

Is the world going to run out of water?

In many places the answer is yes – if we continue as we have done. The rest of the world could learn a lot from Denmark, one of the few countries to have reduced its water consumption.

Water is a vital resource for our homes, industrial production, food production and ecosystems. But the world’s water consumption is increasing dramatically, and in many places, obtaining enough water is a huge challenge.

The major cities of Cape Town in South Africa and Chenai in India have spoken of ‘day zero’ as the day when, unless it rains beforehand, there will be no more water running out of taps. In many places in the USA, India and China, aquifers will be emptied in the foreseeable future if the current, unsustainable pumping of water continues.

In their most recent annual reports on the largest global risks, the World Economic Forum has consistently listed ‘water crises’ among the most significant threats – well ahead of issues such as terrorist attacks, food safety and financial crises.

What kind of challenges can we expect in the future, and how can we find solutions to the problems concerning water?

Watch out for water stress

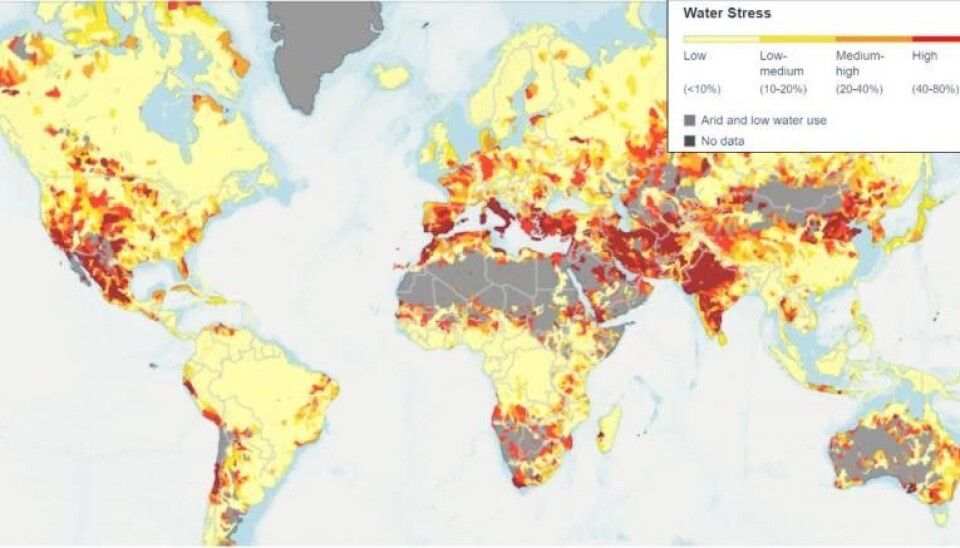

A good indication of an area’s water scarcity is the so-called water stress index that indicates the proportion of renewable resources (precipitation minus evaporation) used in society (see figure 1).

In areas with water stress levels of more than 20 percent, special efforts are necessary in order to obtain sufficient water. The closer the water stress level gets to 100 percent, the more expensive it becomes to solve the water insufficiency in a sustainable manner.

The diagram shows that areas with high water stress levels appear in relatively dry areas with large populations, such as the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Central Asia, most of India, northern China, western USA and Mexico.

Water shortages can severely damage economies

Climate change will result in many areas that are currently affected by water stress becoming even drier and therefore more adversely affected, while other (fewer) areas that are dry today will get more precipitation and therefore less water stress.

In the year 2000, approximately 2.4 billion people, or 40 percent of the world’s population, were living in areas with high levels of water stress (more than 40 percent). This number is expected to increase to 4.2 billion (47 percent) in 2050 due to population growth, economic growth and climate change.

The World Bank has estimated that the effects of climate change on water resources in 2050 could result in a decrease in GDP of up to 10-15 percent in certain dry regions in Asia and Africa.

We can no longer waste the world’s water

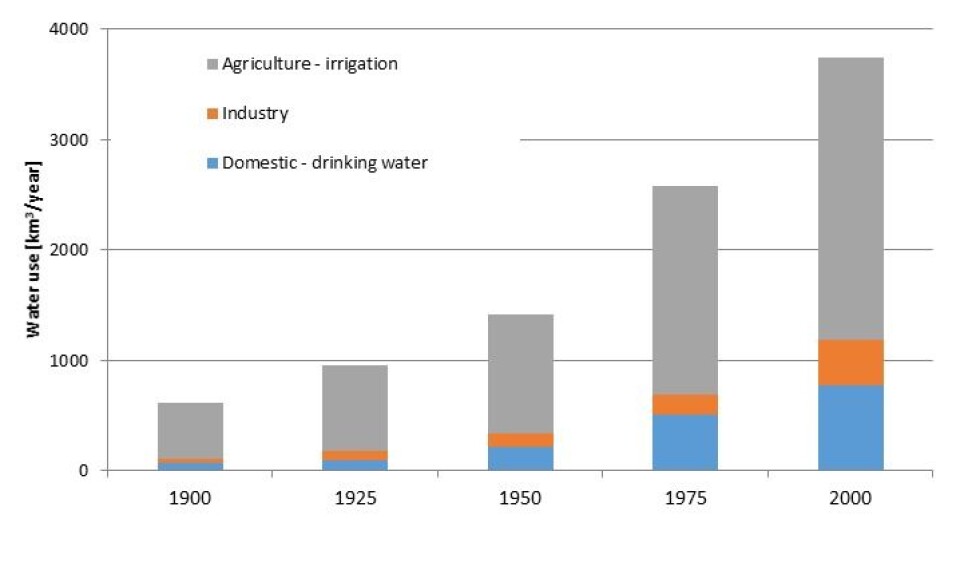

Water consumption in the world has increased as we have grown in number and economies have grown (see graph 2). As evidenced in the UN’s sustainable development goals, safe water and sanitation (sewage etc.) are essential for public health.

Water supply is also a prerequisite for many of industrial products.

Agricultural irrigation, which accounts for the majority of global water consumption, is crucial for us to be able to continue producing sufficient amounts of food.

An increase in water consumption is therefore not a negative indicator of the state of the planet in and of itself. The problem is that we simply do not have infinite amounts of water at our disposal.

Therefore, we must consider water a limited resource that we have to protect, meaning that we cannot continue to allow ourselves to waste it.

Denmark may serve as a role model

The great challenges of the world’s water resources require intelligent water management. And in this respect, Denmark has something to offer.

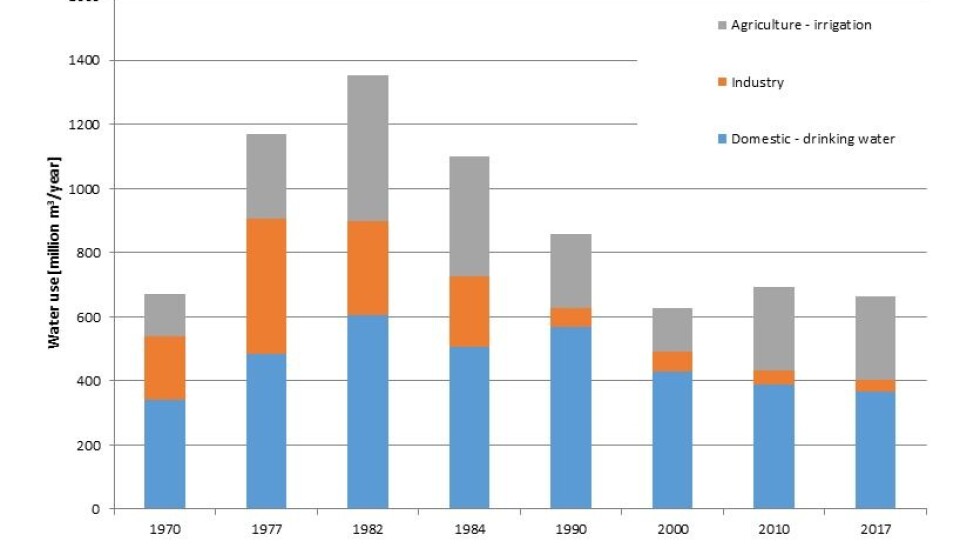

Denmark is one of the few countries that has been able to reduce its water consumption without harming the country’s welfare in any way. Danish water consumption today is approximately 40 percent lower than it was in 1980 (see graph 3), and it is still decreasing.

Denmark managed to reduce the curve through a combination of greatly increased water prices (including green taxes), water saving campaigns, more water efficient technology in households and industry, and a reduction of water loss from the mains supply.

This has been possible because of the political will to introduce unpopular increases in pricing and green taxes.

It has also been crucial that the Danish water supply is owned by consumers and therefore does not have to pay dividends to shareholders. Instead, it can run campaigns for water savings and invest in economically unprofitable renovations of the mains.

The result is that Danish water consumption is significantly lower than in most comparable countries, while the loss through the mains is less than 10 percent, when in many countries it is over 50 percent.

There is ample opportunity for other countries to copy parts of the unique Danish model of success and take advantage of low-hanging fruit.

It ‘only’ requires the political will to introduce and enforce sensible water management strategies.

Rich countries can utilise solutions that poorer countries cannot

Over large areas of the globe, water consumption is now so great that it can impinge on welfare. Climate change exacerbates this issue while simultaneously increasing the frequency and extent of droughts, floods and other natural disasters.

In wealthy countries, the population is able to afford expensive drinking water, so solutions such as the desalination of seawater can be an option.

But this would be economically impossible in poorer countries, just as it would be economically unfeasible to use desalinated seawater for irrigation or to keep the most vital ecosystems alive.

Therefore, we have to secure more efficient use of natural water resources. This will require improved technologies with less water waste in households, industry, agriculture and the mains. It is also necessary to clean and recycle water from industrial production and wastewater from cities.

This requires a visionary water management strategy and its effective enforcement. This can ensure that we use water where it is most needed in society rather than wasting it.

We have more technology at our disposal and we know what efficient water management looks like – but there is a lack of political will to implement water reforms in many countries.

Dry soil could create future water immigrants

Water and climate are interrelated and affect each other. However, whereas climate change is a global challenge where initiatives introduced in one country affect the situation elsewhere on the planet, challenges with water supply are local and must be resolved within the individual water catchment areas.

Nonetheless, challenges with water supply may have a global impact when poor and fragile states are subject to a combination of climate change, water stress, natural disasters and food security shortages.

This kind of cocktail could make it so undesirable to live in certain places that many decide to become climate or water refugees.

While Denmark has the technology and can find billions to secure Copenhagen from rising sea levels in 50 years’ time, for example, it is a much greater challenge to handle migrants who knock on Europe’s door after having had their livelihoods destroyed due to water issues.

We must participate in the development of water solutions on a global scale – then we may avoid ending up in that situation.

Translated by Stuart Pethick, e-sp.dk translation services. Read the Danish version at Videnskab.dk’s Forskerzonen.

References:

Jens Christian Refsgaard’s profile (LinkedIn)

'Grundvandsovervågning. Status og udvikling 1989 – 2017'. Teknisk rapport, GEUS.

'High and Dry: Climate Change, Water, and the Economy', World Bank (2016)

'The Global Risks Report 2019, 14th Edition', WEF (2019)

'Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas', World Resources Institute (2020)

Book a scientist at the Danish Science Festival