Fossil DNA identifies the first seafarers in the Pacific Ocean

Brave seafarers conquered the Pacific Ocean 3,000 years-ago with no chart of compass. Now, DNA is revealing who these sailors were.

Polynesians were unmatched seafarers and conquered the expanse of the Pacific Ocean long before the Vikings reached Iceland, Greenland, and America.

An international team of scientists have now analysed four skeletons to map the genetic material of the first people to settle the Pacific islands of Tonga and Vanuatu between 2,330 and 3,100 years ago.

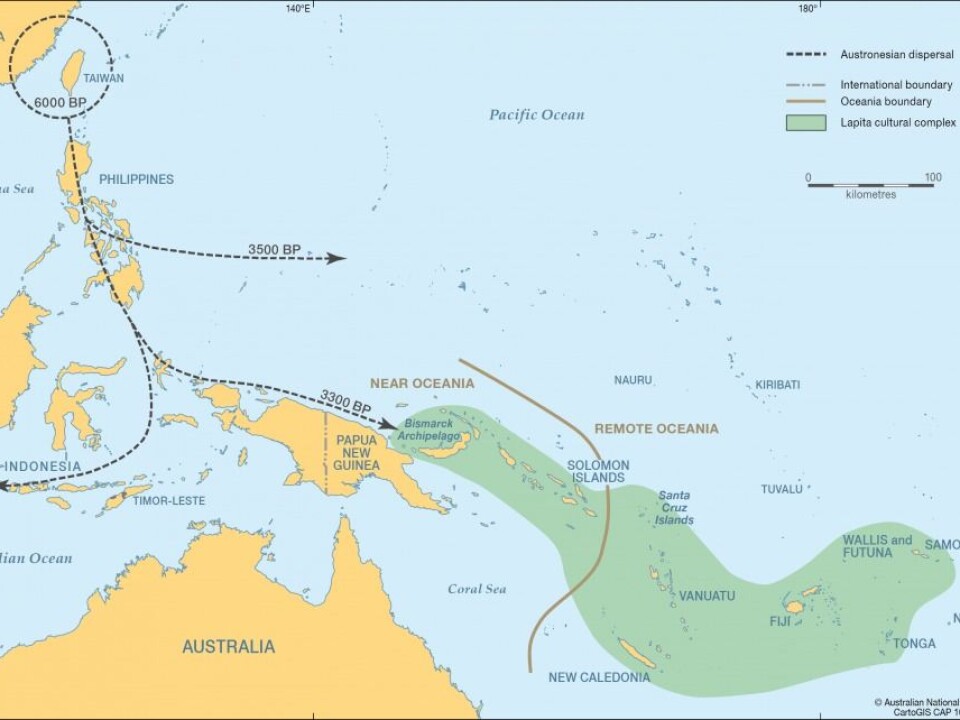

“[A group of] people from Taiwan rowed out into the ocean, and didn’t mix with the people who had lived in New Guinea for much longer than anyone had thought,” says lead author Pontus Skoglund from Harvard Medical School, USA, and Stockholm University, Sweden.

The research provides insights into the people who mastered seafaring and navigation to populate a vast region that stretches half way around the planet—from Taiwan to Easter Island. It also tells us when and how they did it.

“It’s the first study to use modern genome-mapping technology to look at fossil DNA from Remote Oceania. We’ve successfully done it in Europe, but we’ve had less success in the rest of the world. It’s exciting because it gives fascinating new insights into ancient human migrations and demographics,” says Hannes Schroeder, an expert in ancient DNA at the Center for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. Schroeder was not involved in the new study.

The study is published in the scientific journal Nature.

Navigation by testicles

European seafarers could not believe their eyes when they first encountered people in Polynesia in the 1600s.

Academics in Europe believed that the Polynesians must have been the survivors of a devastating natural disaster, where an entire continent, Lemuria, sank into the sea. They thought that the Polynesians had escaped by climbing up to the top of the mountain peaks that then became the islands of Polynesia.

It took more than 100 years before this view was updated by the famous explorer, Captain James Cook. He discovered that the Polynesians were formidable sailors who built seaworthy canoes and navigated hundreds of miles of open water by following ocean swells, reading the stars, interpreting cloud formations, and sea birds.

They also used ocean temperature as a guide—measured by dunking their testicles in the water.

The Polynesians came prepared with agriculturists on board, who brought crops and domesticated animals like pigs and chickens.

“Expansion of agriculture happened in many places around the world over the last 10,000 years, but we know almost nothing about what happened outside of Europe. This gives us one piece of the puzzle,” says Skoglund.

Read More: World’s oldest fossil plants could rewrite life's early history

Lapita culture is a mystery

Skoglund and his colleagues have now mapped the DNA from people of the Lapita culture—a group of agriculturists, named after a type of clay tool discovered by archaeologists near New Guinea and dating to around 3,400 years ago.

From here, the Lapita culture spread east to the islands of Vanuatu and Tonga, and on to the Pacific Ocean in the first ocean going vessel.

But precisely who they were and how it happened has been the topic of academic conversation for some time.

Modern day Polynesians carry a mix of DNA from East Asia and Papua New Guinea.

Papua New Guinea was first colonised by modern humans around 40,000 years ago. Some geneticists though that this was the result of a slow trickle of people from East Asia, who met and mixed with people of New Guinea, and that their descendants went on to spread agriculture and their culture further.

Others think that the islands were populated in a fast wave of migration, and that these people later mixed with the locals.

But the fossil DNA can now tell us exactly who the first people on Vanuatu and Tonga were.

Read More: The ‘Godfather’ of bioarchaeology is moving to Denmark

Lapita culture is a “missing link”

Analyses of the skeletons show that nearly all the genetic material matches East Asian ancestry of the modern Polynesians, while almost nothing matches the Papuan DNA.

This means that the Laptia people cannot be the result of a mixing between the local Papuans of Papua New Guinea.

“The Lapita people are a “missing link” to the Asian ancestry of all Pacific Ocean people today,” says Skoglund.

Read More: Ice Age Europeans migrated back to Africa

Parallel to spread of farming in European

Skoglund and his team are now able to follow the East Asian roots back over the Philippines and Taiwan, which supports the idea of a quick migration to Papua New Guinea and the Remote Oceania.

The express route is also supported by the fact that the Lapita culture is only found along the coast, which suggests that the agriculturists did not meet local people.

“The fast migration of these people with a new lifestyle and technology is a possible parallel to Europe. Here, the first people spread from Anatolia without mixing very much with the existing hunter-gatherers. The mixing came later,” says Skoglund.

The scientists date the later migration to Oceania to around 1,500 years ago and guess that this was made up of descendants of the tail end of the express route, mixed with the Papuans of Papua New Guinea.

------------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex