Fences are disrupting African wildlife on an unprecedented scale

An ecological tragedy is unfolding in Kenya, as fences go up and prevent migrating animals from accessing water and food.

The Greater Mara region in Kenya is famous for its annual animal migrations--one of the world’s natural wonders.

The Mara ecosystem is home to the largest number of Savannah species in the world, including wildebeests, zebras, elephants, lions, and giraffes. All of them are entirely dependent on being able to roam the landscape in search of food and water.

But in recent years, an effective barrier has been thrown up: fences.

In a new study, researchers examine the negative impacts of fencing on wildlife migration—and it’s not looking good.

“From an ecological perspective, it’s a huge tragedy. The open grasslands are becoming smaller and smaller and one of the world’s largest animal migrations is being blocked right now,” says Assistant Professor Mette Løvschal from Aarhus University, Denmark. She is the lead-author on the study, which is published in Scientific Reports.

“The animals are entirely dependent on being able to roam freely to follow supplies of food and water in the region,” says Løvschal.

Fences are poison for the ecosystem

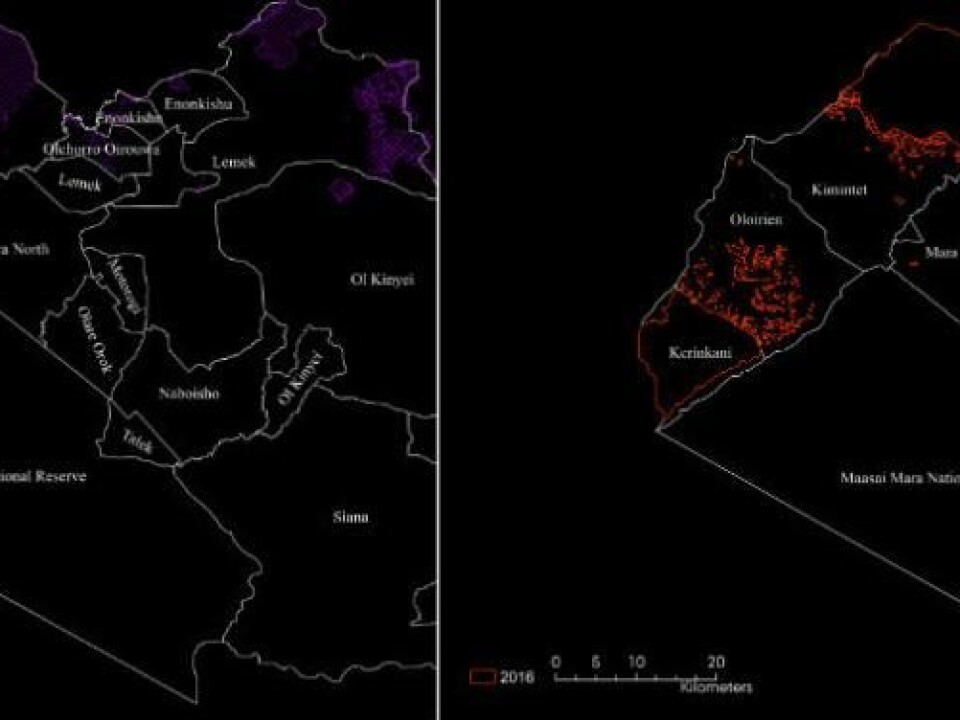

Satellite photos show how areas where animals used to be able to roam freely are quickly being taken over by small, enclosed plots of land.

It is a big problem for the 1.2 million wildebeests and around 200,000 zebras that annually migrate in search of water and food from the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania to the Greater Mara area in Kenya.

The animals follow the migration of the seasonal rains and the fresh grasslands that bloom as a result. It is one of the world’s biggest migrations of large mammals.

Even less migratory animals like elephants depend on being able to roam in search of food and water.

See the great migration from Serengeti in Tanzania to the Greater Mara in Kenya. (Photos courtesy of ExpertAfrica.com / GIF by Kristian Højgaard Nielsen, ScienceNordic)

“Fences are simply ‘poison’ for the ecosystem, as they hinder the migration of large mammals like wildebeests and zebras. If fences become more widespread, then the ecosystem will collapse,” says senior author Jens-Christian Svenning from the Department of Bioscience at Aarhus University.

“We’re afraid that we’re too late”

Satellite pictures between 2010 and 2014 clearly show the rapid appearance of fences between 2010 and 2014.

“We were shocked at how widespread they are—especially that most plots appeared in the last two years. When things move that fast, it’s indicative that it could quickly become a disaster,” says Løvschal.

Unless something is done to curb the development, she does not have much hope for the future.

“Animals will react differently to a large grazing area being cut off. Initially, a halved population might maintain itself, but then it starts to go downhill. There’s still a fair number of wildebeest left in the world, but there’s not many elephants left, and we’re worried that we might be too late,” says Løvschal.

Only cattle left

Concerned, and with satellite images in hand, Løvschal and her colleagues travelled to the Greater Mara to find out what was going on.

As an archaeologist, Løvschal has studied enclosures of Northern Europe, and has seen several historical examples of how devastating they can be for wildlife.

But while archaeological sources can say with reasonable precision when, and how quickly land was enclosed, they often hit a brick wall when they want to know why the land was enclosed.

Meeting the local Maasai was an opportunity for Løvschal to get the why directly from the people building such enclosures.

Her initial outrage quickly dissipated after speaking with them.

“The people who live there own nothing but their cattle. Most have no power, no access to clean drinking water, very little infrastructure. So of course they do what they can to ensure something better than just survival,” says Løvschal.

Fences are a natural reaction

Enclosures in the Greater Mara go up for many reasons, among them is a rising population, climate changes, and changes in land tenure traditions. In the Greater Mara, the human population has increased by ten percent each year—compared with just 2.4 per cent in East Africa.

Increasing population, combined with greater demand on resources, is forcing the local Maasai to abandon their traditional nomadic way of life and settle in one area with their cattle.

“People live very close to one another in these areas, and when it becomes a permanent feature, this means that they need to mark their land with fencing. It’s a way of regulating social tension and securing access to resources. When land space becomes too contested to move around freely, the only option is to build a fence,” says Løvschal.

Giraffes and wildebeest are especially vulnerable

The most recent reconnaissance surveys in the Greater Mara already show an increased loss of animal life due to the fencing, write co-authors Irene Amoke from the Kenya Wildlife Trust, and Dickson Kaelo, from Nairobi University and the Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association, in an email to ScienceNordic.

Giraffes and wildebeests are especially vulnerable but many other animals are at risk, they say.

“The Mara region contains approximately 30 per cent of Kenya’s total wildlife, hosts more than 95 species of mammals with the greatest densities of both wild and domestic herbivores in the country,” they write.

“It’s famous for its concentration of migratory herbivores, providing a dry season refuge for approximately 1.5 million wildebeest, zebras, and large numbers of other grazers, browsers, and predators, including over 500 lions—one quarter of the country’s population—making it the only region in the country [capable of] supporting a viable lion population.”

The fences also pose a more direct threat to wild animals as they can cause injuries at night, sometimes resulting in death, write Amoke and Kaelo.

Local people should get on board with conservation

Conservationists need to get the local people involved if they are to have any chance of turning this tragedy around, says Løvschal.

“In some areas, fences have become symbolic with status. People who don’t have fences are almost bullied—it’s skewed thinking. So some of our colleagues are working to show the local people what the consequences are and explain to them that they can only do this for a limited time,” she says.

But it is difficult, says Løvschal.

“There are good reasons why people are beginning to live closer together, and there are clear advantages to these village-like environments—for example access to schools and healthcare. The problem is that it’s happening in a completely uncontrolled way,” she says.

“We need to make a clear transition, right now, and recognise that some [areas] will be designated to fencing, cultivation, and village communities—but in others we can still do something about it and action needs to be taken. But it’s a fight against time… and perhaps we’re too late.”

-------------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk