Wild horses lost their camouflage because of humans

Scientists find the genetic mechanism that determines the colour patterns of wild horses.

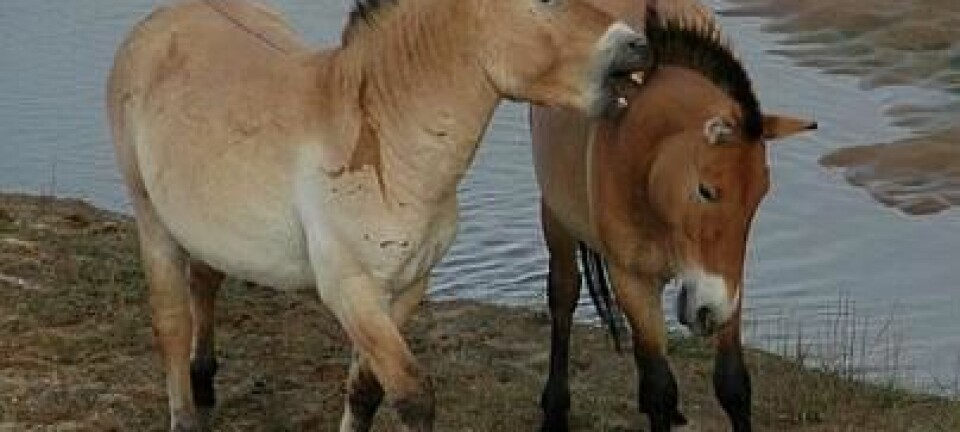

Researchers have discovered the secret behind dun-colour--the warm, light grey-brown hair colour of wild horses.

The colour provided the perfect camouflage for horses in among open grasslands, but has since been lost in most modern breeds.

Now, scientists have identified the genetic mechanism behind the dun-colour, and why the horses lost it.

“Dun-colour is the most fascinating animal colouring," says lead-author Leif Andersson from Uppsala University in Sweden.

"Now we have found an entirely new mechanism behind the camouflage colours of mammals and a new basic understanding of pigment cell biology," he says.

The new study is published in the journal Nature Genetics.

Man has manipulated horsehair colouring

Andersson and colleagues examined genes from 5,000-year-old and 43,000-year-old horses. Bright colours, it seemed, only became widespread after humans domesticated them.

"This gives us a way to really travel back in time and follow exactly how and when humans began to change the colour of horse hair," says Dr Ludovic Orlando, an expert in fossil DNA with the Center for GeoGenetics, the Natural History Museum, Denmark, who was not involved with the new research.

A natural camouflage

Dun-colours are typical of older horse breeds, and represent the original colouring of wild horses--a warm greyish-blue or light brown.

In the new study, researchers have identified a known transcription factor TBX3 on chromosome 8, which is the gene that determines whether the horse will have dun or non-dun coloured hair.

The researchers found two mutations in TBX3, which determines the hair pigments of tame horses, giving them a distinctive colour.

One of the two mutations (d1) was already present in the 43,000-year-old horse.

"It shows that there’s been natural variation in amongst horses for a long time," says Orlando.

The second mutation (d2) is also of interest to Orlando, because here a whole area of the TBX gene has been lost, and it results in a stronger colouring than mutation d1.

The mutation first became prevalent some time after the domestication of the horse, which according to Orlando and colleagues suggests that man actively selected the strong colours.

A man made colour palette

The original dun-colour provided a camouflage and helped horses to hide from predators in the wild. But domestication inevitably reduced the need for such camouflage.

Before the domestication of horses, the original dominant dun variant of TBX3 kept a tight lid on the possible colour variations.

"The proliferation of ‘non-dun’ variants opens up many different variations of coat colours," says Orlando and points to the enormous variety of colour and patterning on horses today, which were simply supressed by the horses need for camouflage.

-----------------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex