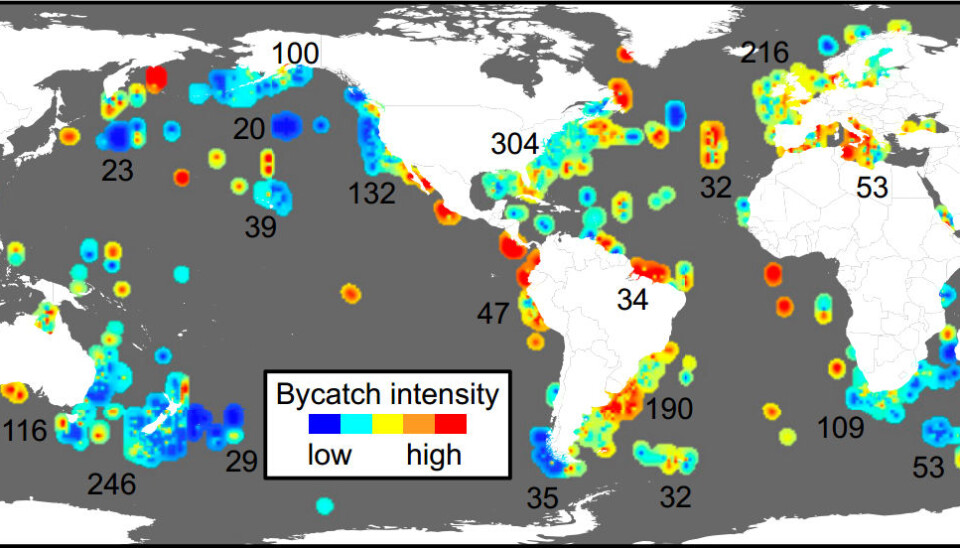

Map outlines global hotpots of bycatch intensity

Fishery bycatch poses a great threat to various endangered species, and to ecosystems in general. Scientists have now mapped out the problem.

Every year, thousands upon thousands of turtles, birds and marine mammals such as dolphins and sea lions find themselves at the end of a fishing line. They are what is known as bycatch, and are thrown dead back into the sea.

Some of these species are endangered, while others are key species in their respective ecosystems. Bycatch – the incidental capture of non-target species – thus presents a great threat not only to the survival of the species, but also to ecosystems in general.

Now, for the first time, scientists have charted the problem on a global scale. This was done to show the public, politicians and decision makers the magnitude of the problem and that something needs to be done about it.

”Biologists have long known that bycatch is a major problem,” says the Danish researcher in the study, marine biologist Ramunas Zydelis, of independent consulting group DHI, who contributed with his expert knowledge on seabirds.

”If you ask the individual fisherman, he might say that he may catch one or two and perhaps a turtle, which doesn’t sound like much. But when we add the numbers from all fishermen in the world, we arrive at some pretty worrying figures which, collectively, have not been available to the public until now.”

The study is published in the journal PNAS.

One million seabirds die every year from fishery

In the study, the international research team collected data from hundreds of studies that map the effects that the three most commonly used types of fishing gears worldwide – gillnet, longline and trawl – have on specific species in given areas.

When put together, all these studies form a picture of which fishing methods result in the greatest amount of bycatch of individual animal species in various regions.

If you ask the individual fisherman, he might say that he may catch one or two and perhaps a turtle, which doesn’t sound like much. But when we add the numbers from all fishermen in the world, we arrive at some pretty worrying figures which, collectively, have not been available to the public until now.

Ramunas Zydelis

One of these fishing methods is longline fishing (long lines with baited hooks), which poses a massive threat to albatrosses off the coast of South America.

Today, 19 out of 21 albatross species are endangered and on the brink of extinction, and this is partly thanks to longline fishing.

Zydelis explains that longlines alone are responsible for 320,000 seabird deaths per year, while the other major culprit, gillnetting, inadvertently catches 400,000 birds per year. Both of these figures are conservative estimates.

”To say that bycatch is responsible for 1,000,000 dead seabirds a year is probably not far off the mark. Our findings, unfortunately, do not come as a big shock to us who have been studying bycatch for years, but these are nevertheless some pretty staggering statistics,” he says.

The albatross can be saved

Zydelis hopes the new study can help visualise and increase the focus on bycatch, so that interventions can be made in the future to reduce these huge figures.

When it comes to the bycatch of albatrosses and other pelagic seabirds, fishermen can play their part in greatly reducing the treat by making small changes to the way they work.

When albatrosses die on the longlines it is because they follow the fishing boats and grab the bait – and the hook – when the line is thrown overboard.

The heavy lines then pull the albatrosses down into the water where they drown.

If the fishermen used additional weights to make the lines sink faster and use colourful materials on the lines behind the boat to scare off the albatrosses, the albatross death toll could be reduced by 90 percent and possibly even more, explains Zydelis.

“This is a simple method for reducing the death toll, but it needs to be done locally with the fishermen. This is already being done in many parts of the world to reduce bycatch of albatrosses, and it appears to reverse the trend,” he says.

“However, there are many other endangered species, and we always need to take care not to shift the problem from one species to another when we encourage fishermen to change their working methods.”

-----------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther