Women and children aren’t saved first

It’s a myth that seamen give women and children priority when ships are sinking. Women have much less chance of surviving and children are even worse off.

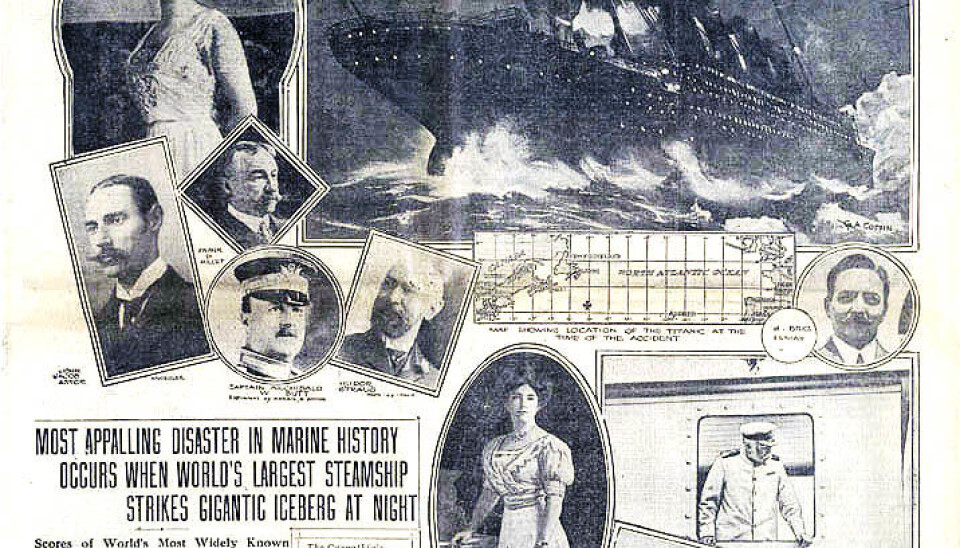

The century-old story of the Titanic is well known:

When it struck an iceberg, the men on board the ocean liner gave women and children priority access to the lifeboats. As a consequence, the odds of survival for women were three times higher than for men.

The notion that women and children should be evacuated first has proliferated in popular culture since the Titanic sank and now it’s seen as a common maritime social norm. It’s called the unwritten law of the sea and such chivalry is regarded as a trait among mariners.

Swedish researchers now say this is hogwash.

In an evaluation of 18 major disasters at sea from around 1800 to today, they found that women have only half as much of a chance of surviving as men. The odds for children to survive are even slimmer.

Men had twice as good odds

The fates of more than 18,000 people at sea were decided in the 18 shipwrecks analysed by the researchers in this study.

Economists Mikael Elander and Oscar Erixson at the University of Uppsala in Sweden have looked at several factors, including the odds of survival for crew members compared to that of the passengers, whether the captain’s behaviour have any impact on the results and whether the ratio of women to men on board have any significance.

In general there is little indication that this form of chivalry is a nautical norm:

Women had a bit less than an 18-percent chance of surviving these calamities at sea, whereas men had twice that – nearly 35 percent.

In fact, women fared better than men in just two of the shipwrecks: the Titanic in 1912, and aboard the HMS Birkenhead, which went down in 1852.

The latter, a British troopship, was the shipwreck that established the protocol of women and children first, but on this steam frigate the women comprised just a little over one percent of the passengers.

“We were really surprised by these findings. We’d expected the norms to apply,” says Elinder.

The crew before the passengers

Elinder and Erixson started their study of the myth by investigating the Estonia tragedy in 1994. The sinking of the ferry Estonia, which sailed between Tallinn and Stockholm, was Europe’s biggest sea disaster since World War II. Only 137 of the 989 people on board survived.

Of these 137, only 26 were women.

“In this particular wreck, men had a four-fold chance of survival. Estonia was also one of the disasters in which the crew had better odds than the passengers,” says Erlinder.

According to him, some countries have regulations, not just a norm, specifying that the crew must help the passengers safely to lifeboats and life rafts before boarding these themselves. But in reality this rule is often overlooked, the report states:

In nine of the 18 accidents the crew had an advantage over the passengers. The crew are usually alerted to the accident earlier and are better acquainted with the ship and more accustomed to the sea. So the odds are on their side, unless they choose to help passengers evacuate the ship first.

No differences in survival rates between passengers and crew were found in the other nine accidents. But the passengers had no advantage, as would be expected if they were given priority.

Worst for the children

The figures showed that the children involved in such disasters are worst off. Erlinder and Erixson didn’t have all the data for children, but information was available about how many children were on board for nine of the ships that went down. These indicate the survival odds for children:

“The children had about a 15-percent chance of surviving a sinking, and that’s the lowest rate of all,” says Erlinder.

“We can only speculate on the reasons, but it coincides well with the picture that the most vulnerable victims perish the most," he says. "If each person only thinks about saving his or her own skin, it’s natural for children to fare the worst.”

Aid from women’s liberation

Other factors the researchers included were the share of female passengers on board, how long the voyage had been before the disaster struck and of course how many passengers the ship had in total. None of these had any impact on relative survival rates.

However, the researchers chalked up one positive trend:

The odds for women have improved in the post-WW II years – the rates of survival between the sexes have evened out some, even though men still have the advantage.

Women’s liberation can take credit – women have generally become more capable of saving themselves. Two factors that help in this context are girls getting more swimming instructions and changes in female clothing styles.

It comes as no surprise that it’s easier to swim in jeans than in heavy skirts, copious undergarments and corsets.

The command evens out natural disadvantages

“These are rather depressing results," says Erlinder. "Nevertheless it’s better to know what the situation really is instead of sustaining and believing a myth. This can help people to better figure out what to do when disaster strikes.”

An obvious question rises in a more modern and gender equal world:

Is there really a need for rescuing women before men today? Isn’t that discriminating?

Erlinder thinks the standing orders to save women and children first should remain in effect. Men are usually stronger than women; they have physical and mental capabilities that increase their odds of survival when a ship is going down.

For instance they are better at scrambling out of chaotic and clogged corridors after a ship capsizes. An aggressiveness fuelled by testosterone can help them fight their way to the deck and to better places in line when it’s 'every man for himself'.

“If you give the command to save women and children first there is still no guarantee they will survive more than men would. But it can ensure the two sexes nearly equal chances,” says Erlinder.

--------------------------------------------

Read the full story in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling