Why immigration is such a sore subject for some

Fear of infection and disease could drive anti-immigrant sentiment, shows new research. It is a phenomenon that dates back to our early evolutionary history.

New research casts light on why the immigration debate is such a polarising issue in many countries, and why some have an almost irrational opposition to integration and immigrants.

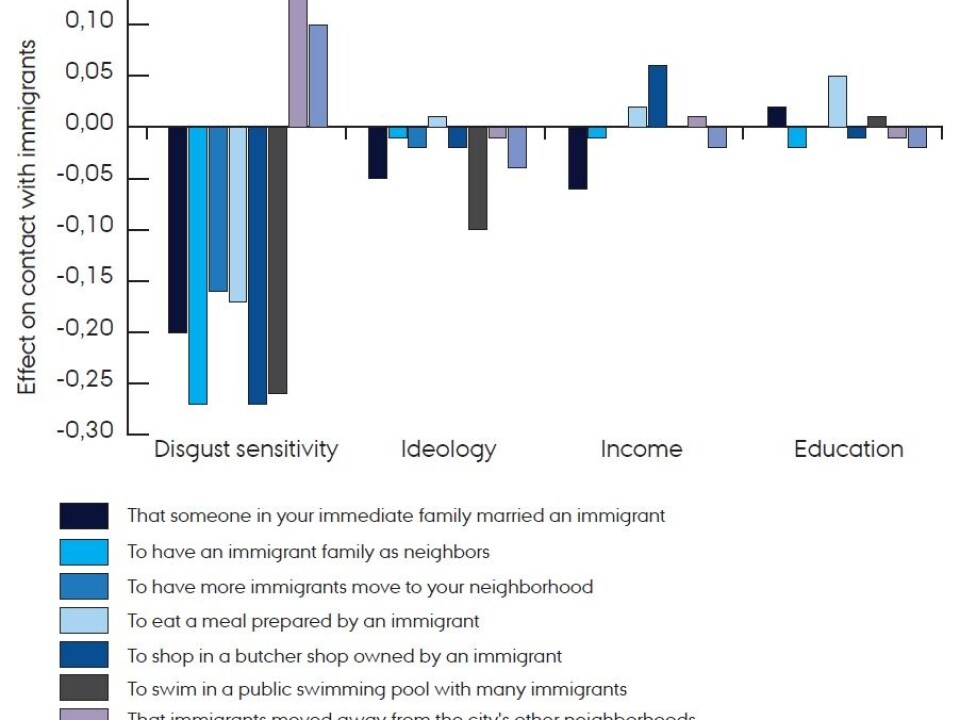

Researchers from Aarhus University, Denmark, have found a connection between people’s fear of infection and their attitude towards immigrants.

People it seems are more reluctant to meet immigrants if they also have a high level of fear of viruses and bacteria.

“Our findings show that the association between resistance to immigrants and fear of pathogens provides an important obstacle to peace and tolerance between ethnic groups,” says co-author Michael Bang Petersen, a professor of political psychology in the Department of Political Science, Aarhus University, Denmark.

The results are published in the American Political Science Review.

Fear of infection prevents tolerance

According to Petersen, this fear blocks two of the “main roads” towards successful integration:

First, they overlook the contribution that newcomers can make to the community, because their fear outweighs everything else.

Second, while contact between local residents and newcomers usually makes people more tolerant of each other, people with an overactive behavioural immune response avoid this contact completely.

This fear prevents them from seeking contact with immigrants and getting to know them.

As a result they prefer immigrants to live separately from the local community and prefer to shop in non-immigrant owned stores, all because of an irrational fear that is a subconscious misinterpretation, and is not founded on any specific experience, say the scientists behind the new study.

Read More: Your neighbour’s skin colour means less if your politics are aligned

Fear is controlled by our “behavioural immune system”

The root cause of this fear is a relatively unknown human trait, the so-called behavioural immune system.

Just like our regular immune system that fights off harmful viruses and bacteria, our behavioural immune system works to protect us from external sources of perceived infection.

Petersen says that the behavioural immune system dates back to our early evolutionary history. Today, it is an integral part of our brain, but one that we know relatively little about.

“We are incapable of seeing germs and viruses with the naked eye. Instead, the immune system is built to overreact and mentally “tag” everything that looks different or unfamiliar as a potential source of infection—whether that’s people with birthmarks or something as innocent as another skin colour or another cultural background,” says Petersen.

Read More: Why do the Nordics trust one another?

Colleagues: A great study

The study has received praise from a number of independent researchers.

Frederik Hjorth, a post-doc at the University of Copenhagen, Department of Political Science, called the study a “Fascinating and important piece of work.”

Professor of political science at the University of Copenhagen, Peter Nedergaard, notes that the study is published in a highly respected journal: the American Political Science Review, which is usually a benchmark of quality.

Assistant Professor Niels Holm Jensen from the Department of Psychology at Aarhus University points out that the study reports a strong correlation—stronger than is usually found in studies of political science and attitudes.

Read More: Trump’s travel ban triggers reaction from scientists

Uncontroversial conclusions highlight the importance of our past

Matthias Clasen, who studies evolution at the Department of Communication and Culture at Aarhus University, describes how the behavioural immune system is unknown to many people, including many behavioural researchers. But it is gaining momentum in many fields of research and the concept is “completely uncontroversial” today.

The new study is completely in line with his own research and findings that are increasingly being presented at scientific conferences, he says.

“Focusing on the psychological and behavioural component of our immune system has proven very productive in various domains, including political psychology. I think this study is really interesting, because it shows how much you can explain human behaviour by understanding our biological evolution.”

“It’s especially cool because it’s so contradictory that our prehistoric existence as hunter gatherers affects how we vote in a parliamentary election in 2017. But the study shows that our past is very relevant,” says Clasen.

Read More: Immigrants help Norwegian companies to think differently

What are the solutions?

Right now, scientists do not know how the behavioural immune system is regulated in each individual person, so they cannot tell why the system overreacts in the way that it does.

According to lead-author Lene Aarøe, who studies political psychology and communication at Aarhus University, it looks as though the system calibrates its response to the level of the perceived threat and to the costs associated with trying to avoid contact with immigrants.

For example, it can be a cost to refrain from renting a room to an immigrant, avoiding going to a particular store because it is owned by immigrants, or not making business deals with someone.

Through experiences involving direct contact with immigrants, the immune response may be mitigated as the stressed behavioural immune system slows down so that contact can go ahead, which could then further mitigate the immune system response, says Aarøe.

“We expect that contact with people of other ethnicities should be continuous and positive in order to change the perception of immigrants among people with a hyperactive behavioural immune system, because it operates on the logic of ‘better safe than sorry’,” says Aarøe.

You can read the entire scientific article on Aarhus University’s website.

---------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex