Why do we spare civilians in war?

Neither compassion nor charity were the reasons why Western soldiers spared enemy civilians in war, new Danish research shows.

Soldiers get killed in war. That’s the way it is.

But it hurts us more when people not in uniform lose their lives, despite the fact that a soldier who gets killed just as well can be someone’s boyfriend, son, father, daughter or best friend -- just as any civilian.

So why do we actually distinguish between soldiers and civilians? Gunner Lind, Professor of History at the Saxo Institute of the University of Copenhagen, has found answers to this question.

“Soldiers easily got into difficulties using their energy to fight civilians. So the practice was introduced, according to which soldiers would do their best not to harm civilians who refrained from taking part in acts of war,” says Professor Lind.

The military historian has presented his research in a new book, ‘Civilians at War’, in which a number of Danish and international researchers have examined the development of the concept ‘civilian’ from the 16th century up until our modern era. His research begins at a time when the brutality and customs of war of medieval times still applied.

“We all have the impression that the Middle Ages were extremely violent and that’s not far from the truth. The level of violence was really high,” says Lind.

Rules of law laid down by church father

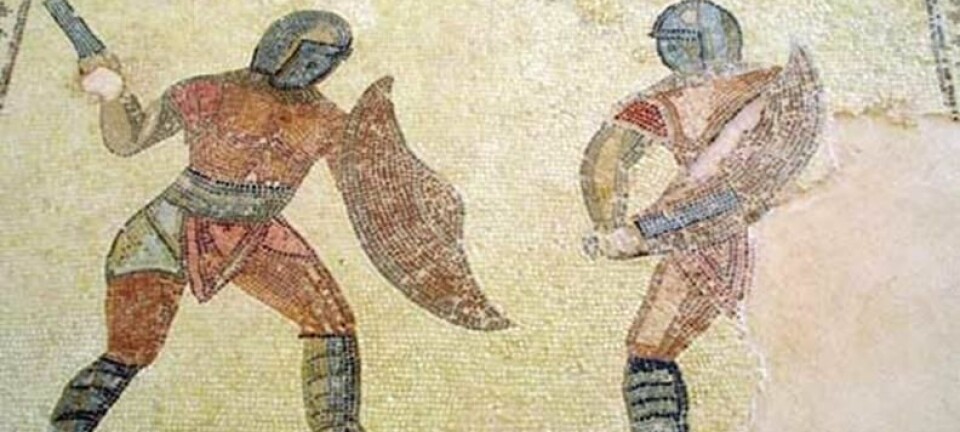

In the Middle Ages everybody carried a weapon. Peasants might not have had swords but they had daggers or axes which they used for their work on the farm.

Conflicts in the form of rebellion, feuds or actual war could arise out of the blue because violence was a tool everyone used. When the state or a squire entered into a feud they would gather local peasants, who would bring along their own weapons. In addition to this, a warlord could hire professional warriors and draw on the services of the nobility, who had spent their youth training in the art of war.

Learned Christians and those in power in medieval society saw it as quite legitimate to go to war, despite the moral imperative of the Biblical Ten Commandments: “Thou shalt not kill”.

Augustine of Hippo, also known as Saint Augustine or Saint Austin, who lived in the fourth and fifth century A.D., asserted that there was such a thing as just war, in which Christians could legitimately be involved.

Christians: you may kill, but spare the innocent

Killing in a just war could be justified if one’s adversaries had committed a grave injustice, such as declaring war on, or threatening the lives of, Christians. This was the reason for the preliminary declaration of war in 1095 which led to 200 years of crusades against Muslims.

Among adversaries, however, there would theoretically always be innocents who had nothing to do with the grave injustice committed, and it was deemed that they should be spared by the warring parties.

Was anyone automatically innocent? For instance women or children?

“Children, yes. But women -- we can’t be sure of that,” says the historian.

He explains that women had little influence in the society of the day, and children absolutely none whatsoever. The Christian thinkers of the day, however, disagreed as to how innocent women actually were in war, and some held the belief that women could be held to account for an adversary’s unjust actions and thus be held responsible.

Professor Lind does not think the concept had much significance in practice. It was not possible, for instance, to keep a town under siege without its children suffering as a result. Hunger and disease invariably followed in the wake of a siege.

Warfare became professional

The concept of innocence prevailed in war etiquette until the 18th century. In the 17th century, however, a new concept appeared. The word ‘civilian’ took on a new meaning. Until then, the term had only been used to describe people who were not clerics.

During this time the kings assumed more political and military power. The state, and with it the king, gained a monopoly on the exercise of violence (see box at bottom of article). The state had the sole right make widespread use of violence. The king got his own regular army.

“In the 16th and 17th centuries, war ceased to become an event to which ordinary people turned out bearing their own arms,” Lind explains.

Now, soldiers in uniform were ready for war all year round. They were trained, paid wages, given weapons, and were subject to military legislation -- unlike people who were not soldiers.

At that time, the military accounted for a large portion of society. The administration thus required words to describe people who are not in the military. Lawyers and scribes began to use the word civilian which was previously used to describe the opposite of a cleric, namely a perfectly ordinary man who was not in the service of God.

Soldiers: sparing civilians was shrewd

Professor Lind’s study, based mainly on examples of the use of the term ‘civilian’ in old Spanish, English, Danish, Swedish, and French dictionaries, reveals that the administrative term as used in the 18th century was given basically the same meaning it has today. This came about because the soldiers chose to prioritise who they were to fight against.

Professor Lind mentions an example of this taken from a source used in his research:

The Spanish general, Ricardos Carillo, wrote to the nearest French general when he was on his way into France with his army in 1793 during the French Revolution (1789-1799).

“Since the rules of war do not permit peasants and citizens to own, use or carry weapons, something neither you nor I would like to see as it would lead to the country’s rack and ruin, I therefore declare -- and hope Your Excellence’s humanity will lead you to declare the same -- that any citizen or peasant who carries a weapon or has one concealed in his home, and especially if he uses these against my troops or villages I have captured, whether he calls himself a partisan or whatever: if he is not in the service of a military unit and as such bears its uniform, token and equipment … then I will instantly have him hanged and will be entitled to do so,” wrote Carillo and continued:

“On the other hand, my troops will never rape or commit murder, but respect the property, goods, freedom and personal safety of all peaceful peasants, regardless of their political persuasion, so long as they stay at home in their villages and homes and live life as usual.”

The soldiers’ new approach to war was due, according to the military historian, to the fact that during a war the armies would move around among agricultural communities, where they had to find food and a safe place to sleep.

“So it made very good sense to apply the civilian concept in enemy territory,” says Lind, who explains that this practice ultimately became the international law we know today.

Power of the masses brings civilians into focus

Searching for the term ‘civilian’ in a database containing all the newspapers published by The Times of London over the last 200 years reveals that the meaning of the word ‘civilian’ as it was in the 18th century has changed from being the practice of soldiers and become the conception of ordinary citizens as to what is right and what is wrong in war.

However, it was not until after World War II that the concept was written into international law.

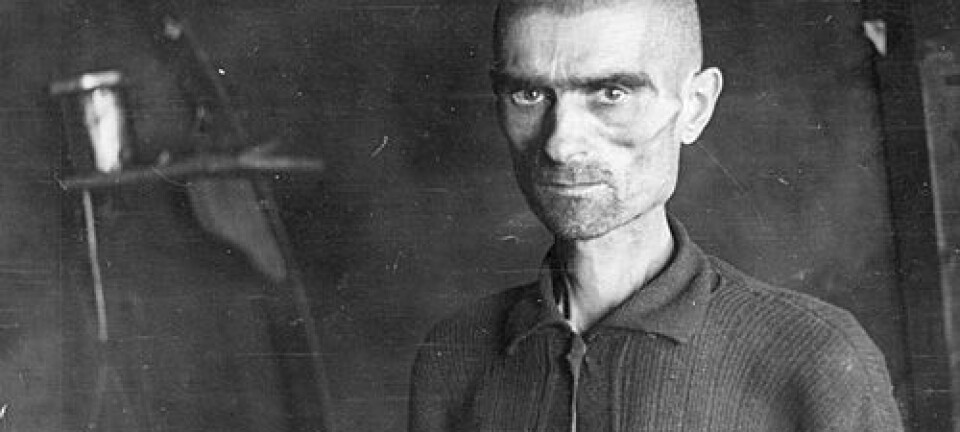

According to Professor Lind, this was done on the background of the atrocities which had taken place on the Eastern front and in China during the world war.

Also of great importance is that fact that the individual has assumed greater significance in purely political terms.

“From the 19th century onwards, ordinary people began little by little to become more important. Specifically, ordinary people get more and more political power. They get most power in democratic societies, but also under dictatorships and in pseudo-democracies. Here, the leaders also fear ordinary people and attempt to get them on their side,” says Lind.

He believes that the civilian concept has greater significance today than ever before. It has thus become part of the warmongers’ strategy to accuse their opponents of violating the human rights of civilians.

Civilian concept belongs to the whole world these days

Professor at the Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies at the University of Copenhagen Jakob Skovgaard Petersen has studied Islam and conflict.

He explains that the West were not alone in believing that people who did not carry weapons should be spared.

“For instance, in Islamic law there is a long tradition for sparing women and children in war,” says Petersen.

In addition to that he believes it is important to point out that thanks to international law, the civilian concept has spread to the entire world, where it has been incorporated into local culture.

The concepts of international law are thus no longer the inheritance of the West, but are also used and shaped by cultures in the Third World.

-----------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews