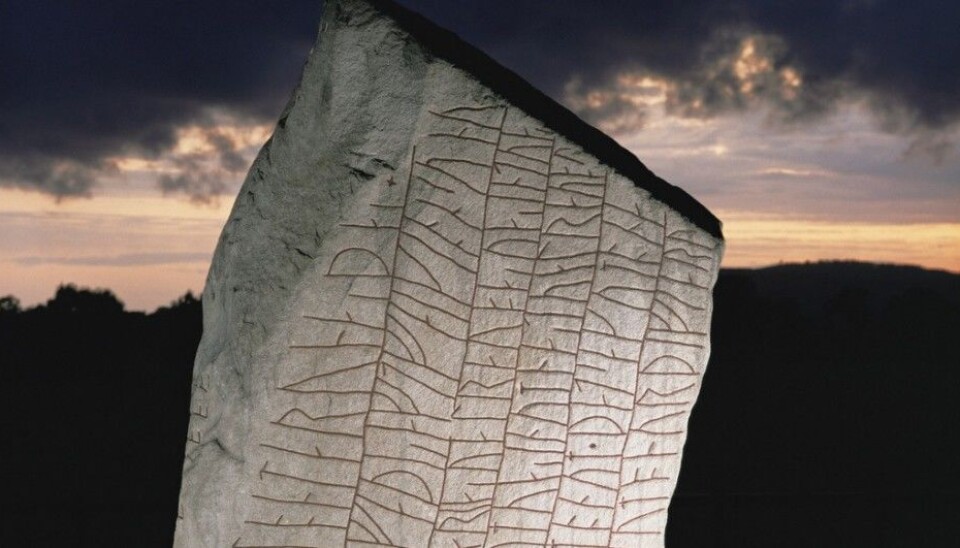

What secrets are hiding in these runes?

A Swedish researcher offers a new interpretation of the runes on the spectacular Rök runestone. “The stone is one of our biggest enigmas,” says a Norwegian runologist.

“In memory of Vemod stand these runes. But Varin wrote them, the father, in memory of his dead son”

Thus starts the text carved into the Rök runestone, which has puzzled researchers since it was discovered built into a 12th century church wall in Sweden’s Östergötland County in the 1600s. It was common to recycle ancient runestones as building materials in Christian churches. The stone has a long pre-Christian runic inscription and is one of Sweden’s national treasures.

We do not know who he was, but Varin probably carved and raised the stone sometime in the 800s, in memory of his son – Vemod.

But the rest of the text has been hard to interpret. Many have made attempts and now the Swedish researcher Per Holmberg of the University of Gothenburg has taken a crack at it. His interpretation is constructed differently, departing widely from the understanding that has been generally accepted for about a century.

“This is a very compelling interpretation and might be a step in the right direction toward understanding more of the text,” says K. Jonas Nordby to ScienceNordic’s Norwegian partner forskning.no. Nordby is a runologist at Follo Museum in Norway.

But first of all, what makes the Rök runestone so special?

A strange stone

The Rök runestone is not like others. First of all is length; it consists of many runes, many more than on ordinary runestones. It also consists of more runic systems, making it all the harder to interpret.

“Most of the runestones from the Viking Age were made around the year 1000 AD, but the Rök stone is somewhat older. Most indications point to it being from the 800s,” says Nordby.

“We don’t have many to compare it to,” he explains. “This makes it harder to figure out.”

But its age is not the biggest problem for a clear interpretation – there are no spaces between the words.

“The runes flow into one another and nothing indicates where one word ends and the next begins. Many of the runes have to be understood contextually.”

Other runestones often have dots or crosses to indicate the separation of words. Some even have traces of paint indicating that some words were given different colours to distinguish them from one another.

Another challenge is the runic alphabet in the Viking Age, which only had 16 runes. This was insufficient to cover all the Norse sounds of speech so many individual runic letters had to represent more than one sound. The issue of which sound they represented has to be understood from the context of the inscription.

“This differs a lot from the modern text we are accustomed to and uncertainties can crop up in translations.”

What does it say?

“Many have tried to interpret the stone and I know of about 60 scientific articles about the inscription,” says Nordby.

The translations and interpretations made in the late 1800s and early 1900s formed the basis for the explanation that has gained general acceptance.

This says the stone describes various acts of heroism in historic wars. An additional presumption is that the Rök stone contains selections or references to sagas and myths which got lost to us through the centuries. This explanation has been included in encyclopaedias.

But Per Holmberg’s interpretation takes a different path. What does he think the stone says?

We need to dive deeper into runes to understand the differences.

Ostrogoth king

The old translation pivots on the Rök runestone allegedly referring to the Ostrogoth king Theodoric the Great, who ruled Italy in the late 400s and early 500s, after the fall of the western half of the Roman Empire.

“This has been a key section of the old translation, which was made by the Swedish researcher Elias Wessén.”

“Researchers have used the Theoderic reference as a framework for interpreting the rest of the text,” explains Nordby.

The University of Gothenburg wrote in a recent press release that in earlier interpretations “this understanding has sparked speculations about how Varin, who made the inscriptions in the stone, might have been related to Gothic kings.”

In his research, Holmberg shows that the Rök runestone can be understood as sharing similarities with other runestones from the Viking Age. In most cases, such runestone inscriptions say something about themselves.

Per Holmberg bases his translation of the Theodoric passage on work by the Swedish linguistic Professor Bo Ralph from 2007.

Ralph suggested that a minor reading error and some nationalistic wishful thinking had tainted the old interpretations. He thought that since experts didn’t know for certain how the words were separated, the passage could be read much differently.

Instead of saying “the bold Theoderic, the chief of sea warriors, ruled over the shores of Reidhavet [the southern Baltic Sea]”, the passage can be understood to be telling about the “noble giant, the chief of the sea warriors, who rode his horse across the expanse of the sky.”

This giant can be a figure representing the day – the Norse god Dagr, according to Holberg’s article, published in the journal Futhark.

If the Theoderic reference is lacking, what would the runes then be saying?

Referring to the reading

“Holmberg argues that these runes comprise a text that actually refers to the stone itself,” explains Jonas Norby.

Holmberg has used modern linguistic theories about runestones to interpret the text. Although the stone differs from even the earliest runestones centuries later from around 1000 AD, Holmberg suggests that it can be read similarly, following some of the same conventions.

A runestone is usually a monument to honour a dead relative and could also refer to inheritances and important occurrences in the life of the deceased.

“The runic text in the beginning of the Rök stone focuses on the runes being a memorial to the departed but in later runestones the act of making the inscription is often emphasised.”

Norby explains that this might mean the runes themselves have a special meaning in the text of the Rök stone.

Rather than describing old sagas and stories, Holmberg thinks the runes tell riddles and poetic stories which in part refer to the actual reading of the text.

“For example, Holmberg interprets the part about the noble giant – Dagr – as a description of the struggle between daylight and the darkness of night. The light of day must shine on the runes for people to read them.”

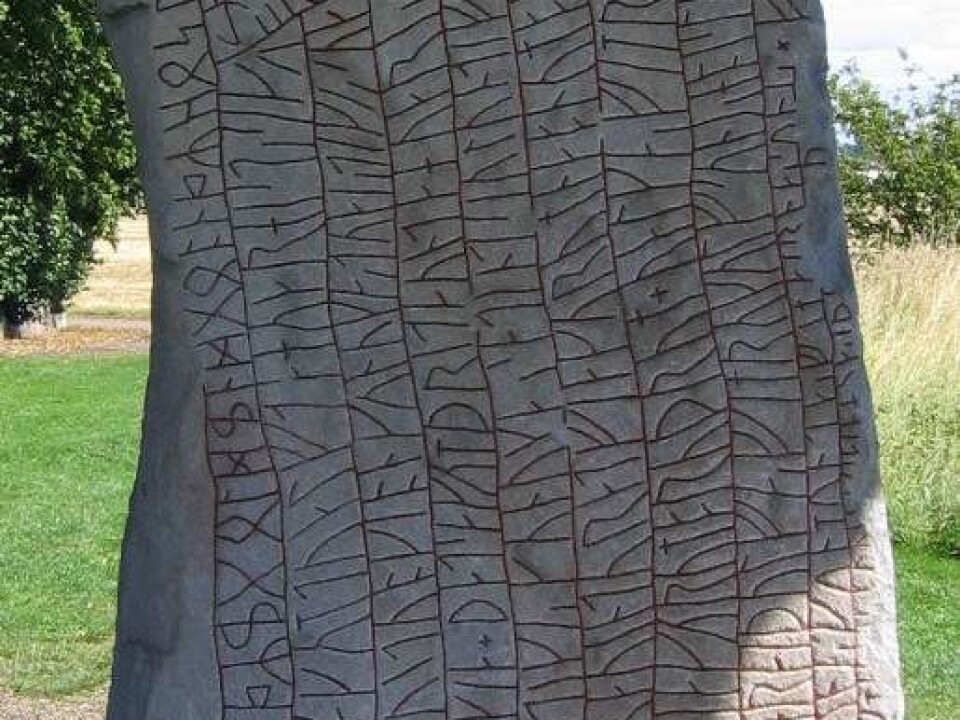

“Those who made the inscription used a variety of runic systems, including coded runes, and this shows that the art of runic writing has been an essential part of the memorial stone.”

How to order the words?

Another novel issue is that Holmberg changes the order in which the words are read, something which has always been disputed regarding the Rök runestone.

He thinks there is a natural way of reading it that has been overlooked. The reader is led around the stone and the text consists of 16 different stanzas.

Some of these stanzas suggest numbering, for instance “the second” or “the thirteenth”. It used to be thought that the text jumped rather mysteriously between these numbers, as if sequences of text were lacking.

“Many have assumed that they refer to parts of myths or texts that have been left out, but that contemporary readers would know of these and would get the message,” says Nordby.

But the new suggested order of the words does not require bridging possible gaps in our cultural references. It literally follows these numerical references. “The twelfth” simply becomes the twelfth sentence one reads, after the eleventh and followed by “the thirteenth”.

“This type of numbering is previously unknown in runestones. But the fact that Holberg’s way of reading it follows this numerical sequence supports his ordering of the inscription,” says Jonas Nordby.

Despite that concession, he does not think this is the definitive final word about the Rök runestone.

“This is not a complete interpretation of the runestone and there are several runes he doesn’t include,” says the Norwegian.

Among other things, the crosses you can see on top of the text are also a special type of runes, but these are lacking in Holmberg’s interpretation. More of such runes are found on the topside as well as the back side of the stone.

“Perhaps we will have to accept that some of this will never be understood. These runes were written by persons with completely different cultural references than we have today. We lack the prerequisites needed to interpret all the details and dimensions of the text,” says Nordby.

------------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling