We lose control of our DNA at age 55

The body starts to seriously lose grip of its DNA after 55 years, and that increases the risk of cancer and other diseases.

Our bodies are born to die, and the decay starts to kick in after we have turned 55. This is the point at which our DNA starts to degenerate, which increases the risk of developing cancer.

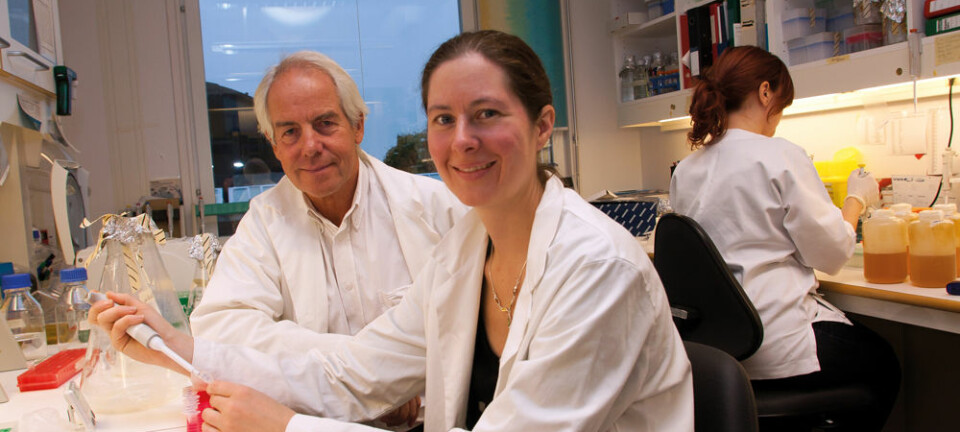

This is the conclusion of a comprehensive genetic study, carried out by a large international consortium, which includes a research team from the Danish State Serum Institute (SSI).

The findings have just been published in the scientific journal Nature Genetics.

“The study shows that our bodies are really good at repairing DNA damage until we reach the age of around 55,” says Professor Mads Melbye, the executive vice president at SSI, who headed the Danish contribution to the project.

Our bodies are really good at repairing DNA damage until we reach the age of around 55. After this point, our ability to fight off foreign or diseased cells starts to decline gradually.

“After this point, our ability to fight off foreign or diseased cells starts to decline gradually.”

Eternal youth – a thing of the past

In recent years, scientists have been busy mapping the connection between an individual’s genetic makeup and the risk of developing certain diseases using the latest technology.

This study, however, is different, says the professor.

The aim of the study was to use this same technology to track in on how long the human body can sustain its effective repair and control mechanisms. In other words, how long the body is capable of repairing cell damage, also known as mutations, so that they don’t take hold of the body.

In principle, the method makes it possible to gain an early indication of whether a person faces an increased risk of developing leukemia.

If a mutation persists, a group of cells emerge whose DNA is slightly different to the other cells in the body.

Each type of cell is known as a cell clone or a cell line, and the amount of these in a person’s body indicates how many cell injuries the body has managed to repair and combat.

Mosaics can trigger dangerous diseases

As we age, we risk developing more than one cell line, and several cell lines form a mosaic, which gives an indication of the risk of developing diseases.

It is these mosaics within a person’s DNA that the new technology is capable of mapping, and the new study has examined the occurrence of this phenomenon over the course of a human lifespan.

“The more mutated cells we allow to gain a foothold in our bodies, the greater the risk of one of these actually developing into a cancer,” says Melbye.

Until we reach the age of 55, this is not a problem. But after this point, a clear change starts to occur in our bodies.

“At this point, the body starts allowing significantly more new foreign cell clones to grow.”

Thousands of people examined

The new technology is known as Genome Wide Association (GWA) and consists of scanning the genome of tens of thousands of people with the aim of finding the tiny genetic bits that identify the various types of cell lines.

In order to identify how many cell lines we typically form over a lifetime, scientists need access to DNA samples from a sufficient number of people from all age groups.

No single research group has access to such great amounts of data, but the problem was solved by establishing the GENEVA consortium, which has collected data in the form of blood samples from a total of 16 studies.

All in all, this amounted to DNA samples from 50,000 people, which has resulted in some highly reliable analyses.

Increase in cell lines through old age

In this phase of the project, Denmark has contributed with 4,000 samples from mothers and their newborn children.

One researcher who has played a central role in the Danish part of the analysis work is senior researcher in genetic epidemiology at SSI, Bjarke Feenstra:

“Up to the age bracket of 55, less than half a percent of the subjects had a mosaic, i.e. more than one cell line,” he says.

“After 55, there was a sharp increase in the percentage, reaching 3 percent at the age of 80, after which it remains constant.”

Could pave the way for prevention of cancer

The study was designed such that the scientists had information on each individual’s entire medical record.

They found that those who had a mosaic were up to ten times more likely to develop leukemia than those who did not have a mosaic.

“In many cases, the mosaics overlapped regions of the genetic material that are known to contain mutations in people with leukemia,” says Feenstra.

He emphasises that in his personal opinion, this is a basic research result (see Factbox). But he does believe the new findings have potential, since they could well prove important in the prevention and diagnosis of leukemia.

“In principle, the method makes it possible to gain an early indication of whether a person faces an increased risk of developing leukemia,” he says.

“However, there is still only a tiny share of people with a genetic mosaic who actually develop leukemia.”

Biological cause remains unknown

In this project, the researchers have only studied leukemia, but they feel convinced that this is a more general phenomenon that also applies to other cancers and diseases. Further studies are needed to establish that, say the two researchers.

“Whether it’s our own ability to repair the DNA injuries that constantly occur in our bodies, which suddenly decreases around the age of 55, or whether it’s our own immune system that slowly loses the ability to destroy foreign cell lines in the body is a subject for future research,” says Melbye.

One point which in Melbye’s opinion the new study has made perfectly clear is that our own body in many ways is our own best doctor. It has an astonishing ability to keep us fit and healthy for many years through a variety of repair and control mechanisms.

“If we learn to understand what it is that changes when we reach the age of 55, we may be able to develop some form of therapy that postpones this point,” he says.

“Such a procedure would most likely have a pronounced effect on the occurrence of certain forms of cancer and would delay the age at which they appear. This would mean an increased number of healthy years,” he says.

---------------------------------

Read this article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther