We become more motivated when we think we're playing a game

New research shows that we tend to get more captivated when we think we're playing a game -- even if it isn't interactive.

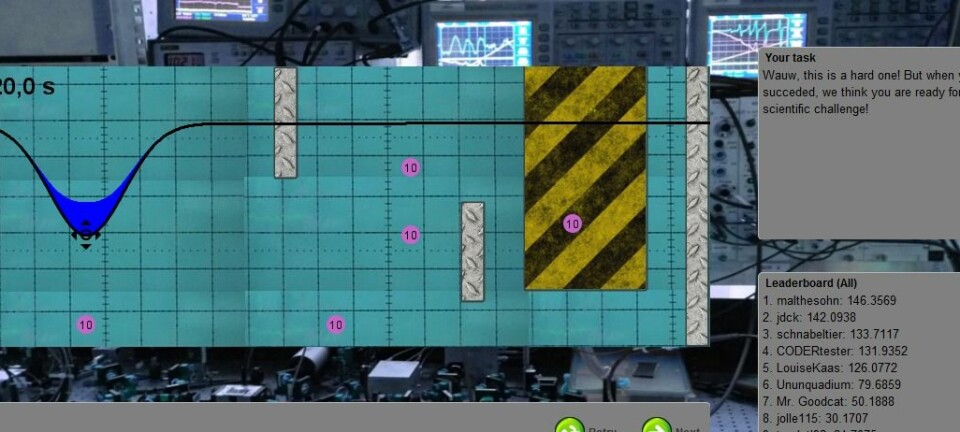

Mundane tasks suddenly become fun if they're turned into a game. This is the idea behind 'gamification' and you might be familiar with the term from apps like 'Zombies, RUN!' and 'Endomondo'.

However, according to a new study, it might not be the game itself that stimulates us -- but rather the packaging: the fact that an activity resembles a game.

That's the conclusion of a new study conducted by post-doc Andreas Lieberoth from Aarhus University.

"Our study shows that it’s not always the game itself but rather people's expectations of playing a fun game," says Lieberoth.

90 psychology students as guinea pigs

The researchers examined the extent to which games motivate people with the help of 90 psychology students from Aarhus University. The students were divided into three groups of equal size.

They were then confronted with different tasks, each group in its own room.

One of the groups split up into smaller groups, which were to play a typical board game which Lieberoth had devised for the occasion. The game was a social gamification of a questionnaire about the psychology study environment.

The game had graphics by a professional game designer and was similar to familiar board games like Trivial Pursuit, consisting of a board, pieces, and a pile of cards. Each card posed a question related to the study environment. The players had to ensure that the other players reflected as thoroughly as possible on the question.

Each player was then awarded points for their efforts, after which they moved their pieces forward according to points scored. The players took turns and the first player to make it round the board was considered the best at getting their fellow students to engage in conversation about the study environment.

The second group were presented with the same game, with the same attractive game board, cards and pieces. Their instructions, however, were quite different. The players took turns to draw a card and help the discussion on its way, in the same way as the first group. But they only moved their piece one square forward on the board.

Although the framework resembled a game, no competition was involved, nor were there any surprises along the way. In reality, the board and the pieces were superfluous, and the questions could just ass well have been asked on a sheet of paper.

The third group was a control group. The students in this group were given the same questions as the other -- but on a piece of paper.

Researchers observed in secret

After an hour, the researchers announced that the game was over and asked the players to remain seated, but told them they could carry on playing if they wanted to.

The researchers then secretly observed how long each group kept on playing.

This enabled them to conduct a behavioural evaluation: was the activity really so absorbing that the participants would continue playing after they had been told they were free to go?

They subsequently assessed the participants' motivation by means of psychological tests.

Turns out that in terms of motivation, it made no difference that one group actually played a game while the other did not.

"There was no distinguishing between the two groups playing board games," says Lieberoth.

How to fool people into thinking something boring is fun

The experiment revealed that so long we think we're playing a game we'll be more motivated.

“Simply putting a game board, some cards, and pieces in front of people makes a statistically significant difference when it comes to motivation. It gives them greater motivation to get involved," says Lieberoth.

The students in all three groups agreed that they had enjoyed a first rate social experience and that the assignment was important in relation to their course of study. Those with a game in front of them, however, seem to have had more fun than the others.

"Or in other words: If you can fool people into believing that they are playing a game they will find banal activities fun," says Lieberoth.

Researcher: an impressive experiment

The experiment is applauded by Torben Tambo, an assistant professor from Aarhus University, who studies how gamification can be used to sell products.

"It's a really exciting way of putting more words to the phenomenon -- because they've been lacking," says Tambo.

On the other hand, he employs a much broader definition of gamification than Lieberoth.

Whereas Lieberoth differentiates between 'gamification' and 'framing' -- as with the experiment's second group -- Tambo sees gamification as a kind of framing.

“Haven't the gamification people simply claimed that they are using a new kind of framing? Gamification is the incorporation of elements of gaming in a non-gaming context. And gaming elements can be interpreted very, very broadly,” says Tambo.

-----------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews