Violent knights feared posttraumatic stress

Knights in the Middle Ages were not the brutal and merciless killing machines depicted on film. New research draws a different picture of the medieval military elite.

Medieval knights are often depicted as bloodthirsty men who enjoyed killing. But that is a completely wrong picture, new research shows.

The knights did not kill just because they wanted to, but because it was their job – precisely like soldiers today. Nor were the Middle Ages as violent as we think, despite their different perception of violence compared to ours.

“Modern military psychology enables us to read medieval texts in a new way – giving us insight into the perception of violence in the Middle Ages in the general population and the use of lethal violence by knights,” says Thomas Heebøll-Holm of the SAXO Institute at the University of Copenhagen, who researches the perception of violence in the late Middle Ages.

“Previously, medieval texts were read as worshipping heroes and glorifying violence. But in the light of modern military psychology we can see the mental cost to the knights of their participation in the gruesome and extremely violent wars in the Middle Ages.”

Violent by nature or culture?

Were the knights violent by nature, enjoying killing? Or was killing something they learned from living in a violent society and culture?

Some psychologists believe violence is latent in our genes, while others believe it is something we learn through training. Heebøll-Holm’s research places the medieval perception of violence somewhere between those categories.

“From crime statistics and letters of pardon, historians can see that people in the Middle Ages were no more violent than we are today,” says the researcher. “But they had a different perception of the use of violence, including lethal violence.”

Back then, people generally had the same concerns about violence as we do today – they were opposed to the use of violence, he explains. In some cultural situations they were forced to use violence, even if it involved murder – and they did so.

“If someone had acted in a way that violated the honour of one of your family members, you were expected to make him answer for his actions, and kill him if necessary.”

Kill and get a pardon

The researcher relates a story from Paris in the 14th Century. A woman was beaten to death by her husband. Her two brothers demanded that the husband pay penance for his actions, but he refused.

Although the brothers felt no pleasure from killing the husband, and even tried to avoid doing so, they felt they were forced to kill him to re-establish their honour.

But instead of punishment the brothers were pardoned, as it was well known that the husband had violated their honour by killing their sister.

“In the Middle Ages, the authorities were too weak to ensure law and order,” says Heebøll-Holm.

“To carry this to its logical conclusion, it was up to individuals to ensure that their honour was not violated or abused by others. This meant that ordinary people had to kill to show the world around them that they were willing to ensure their rights by using the most drastic means if necessary.”

Knights with PTSD

Although they exercised violence in its most extreme form, participating in wars where their comrades were cut into shreds by their enemy’s troops and where they themselves used brutal and gruesome violence against the enemy, medieval knights were not violent by nature or through culture.

But their war experiences could leave them with a very serious case of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), according to the researcher.

During his studies of violence in the Middle Ages he came across a book written by a knight who lived in the first half of the 14th century.

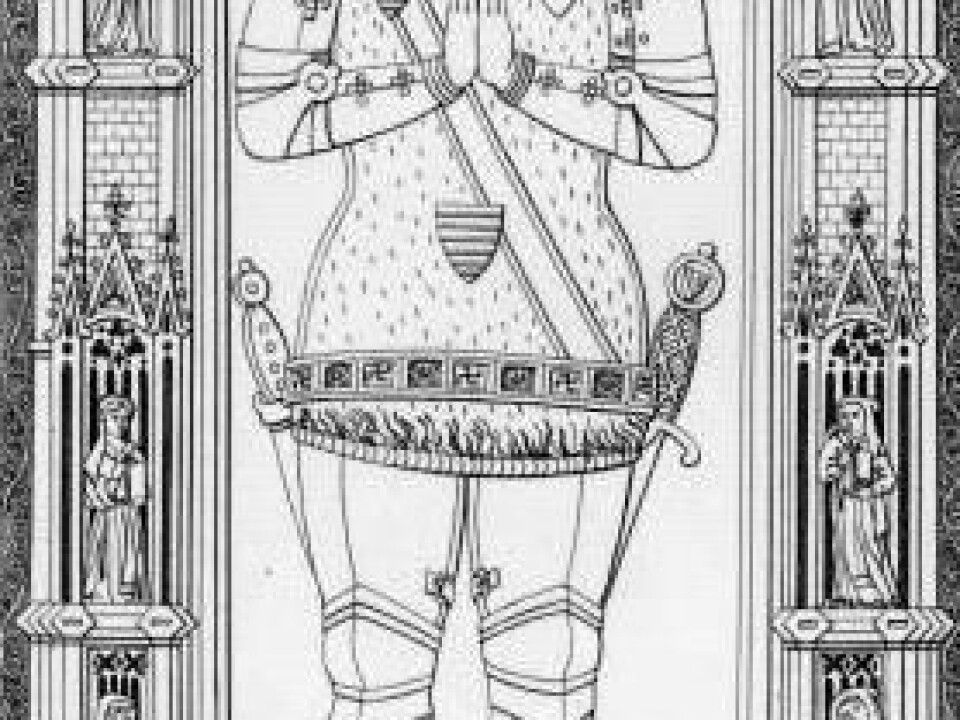

“His name was Geoffroi de Charny, and he was one of the most respected knights of his age. The book, about the life of a knight, included the psychological consequences of being a knight – and they strongly resemble the symptoms of PTSD.”

In his book, de Charny advises knights on how to relate to the fact that they must kill people when they are at war. He also mentions some of the hardships knights face: poor sleep, hunger, and a feeling that even nature is going against them.

“De Charny describes stress factors that we also see related in modern military psychology, including reports from Vietnam War veterans,” he says. “His picture of knights shows they are very remote from the violent psychopaths that we picture them as.”

Fight for a good cause

De Charny also suggested what the knights should do to resist the stress factors. He said knights should fight for a good cause to avoid succumbing to the pressures of war. A ‘good cause’ should be God’s cause – a war for a higher and just cause, to reinstate law and order – and not for personal gain.

“On the one hand we can see that de Charny was a very conscientious man – and in the Middle Ages conscience was regarded as God’s way of telling us how to relate to rights and wrongs.

“On the other hand, he was a warrior who took part in several wars over a period of 30 years, including a crusade to the city we call Ismir. War and crusades are by definition violent,” says Heebøll-Holm.

Read the article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Michael de Laine