Unusual find saved just in time

Paddles dating back to the Ertebølle culture in the Stone Age were recently found in Horsens Fjord, Denmark. They were close to being eaten up by the strong ocean currents.

Archaeologists have known for a while of settlements with surrounding culture layers by the coasts of Horsens Fjord.

In 2008, Peter Astrup of Aarhus University noticed well-preserved bones and processed wooden objects on the seabed. These objects revealed layers that had been heavily degraded by the ocean waves.

After repeated visits to the location and discoveries of objects such as wooden sticks and antler axes, Moesgård Museum, Horsens Museum and Aarhus University launched an investigation in autumn 2010 and again in 2011.

The excavations revealed many interesting finds, the most startling of which were three paddles made out of ash wood.

From the Middle Ertebølle period

Remarkably, the paddles lay partially exposed on the seabed, which to some extent had affected their state of preservation.

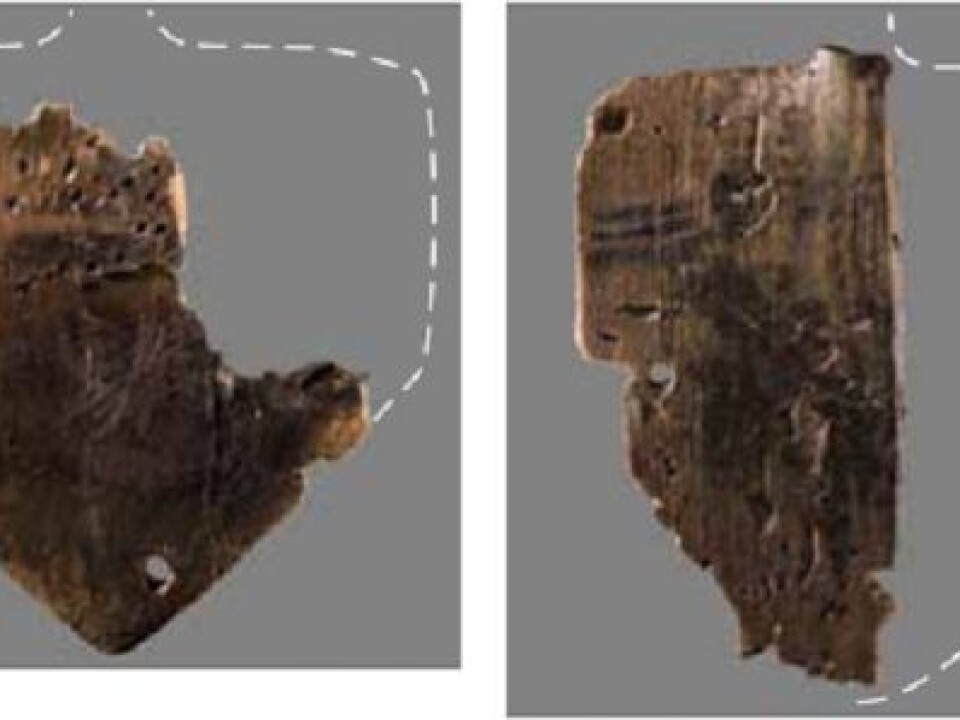

One of them only had the handle intact, and on the second one, around two thirds of the blade was preserved, revealing an original total size of about 20 cm in length, 24 cm in width and about 0.8 cm in thickness.

Cuts on the surface indicate that the paddle blade may at some point also have been used as a chopping board, presumably used for cutting off the heads of fish.

The third paddle was preserved in its full length and had half of its blade remaining. This one measures 103 cm in length, of which the blade accounts for 21 cm. The blade is 22 cm wide and 1 cm thick.

The paddle has been Carbon-14 dated to around 4,700-4,540 BC, which brings us back to the Middle period of the Ertebølle culture.

Many possible applications

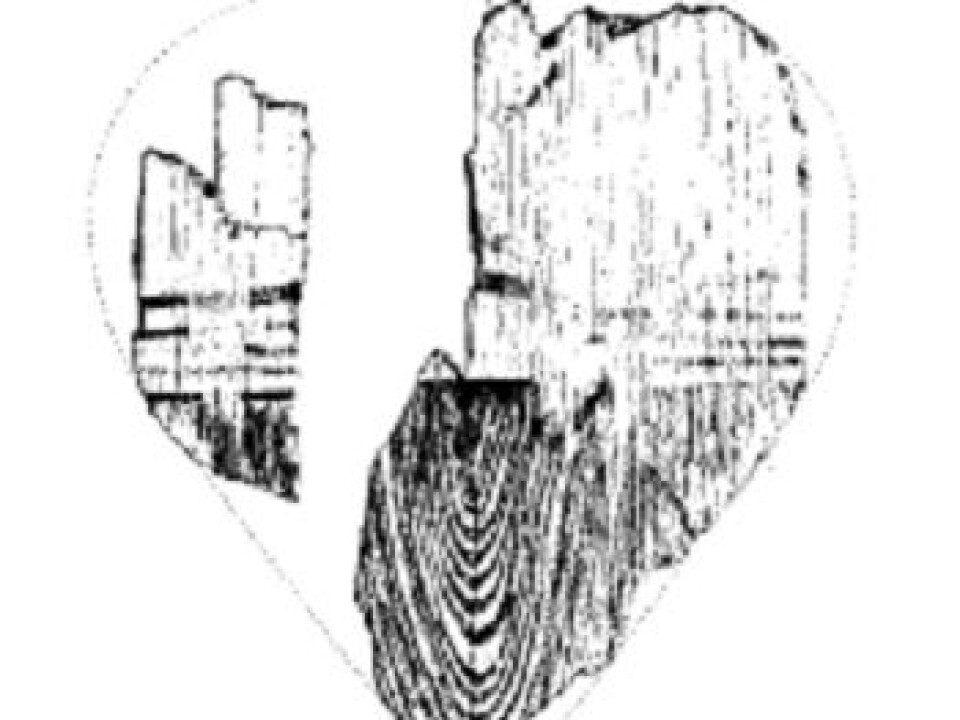

Despite the apparent contemporaneity, the two paddle blades are not identical; whereas one blade was heart-shaped, the other was almost shaped like a spade.

These exact types of paddles are known from several Western Denmark Ertebølle settlements. Previous finds in Horsens Fjord have revealed a spade-shaped paddle blade.

The variation in the shape of the blades could be due to the different uses these paddles had. But that remains uncertain.

Once the mud had been rinsed off, the archaeologists found traces of paint, which has previously mainly been found on paddles from Tybrind Vig, on the island of Funen.

The motives of the painted designs on the paddles found in Horsens Fjord are not quite identical, but the composition is similar.

Patterned paddles far from common

Both paddles are painted in solid black on the lower half of the blade, with three horizontal, parallel lines painted above it.

On one of the paddles these consist of 0.6 cm wide lines, which curve upwards from both edges of the blade toward the centre of the blade, while the other paddle has three separate lines, roughly 1.3 cm in width.

Paint can only be detected on one side of the blades. This may, however, be because the opposite side in both cases is more damaged.

Paddles found in Tybrind have patterns on both sides. Patterned paddles from the Ertebølle culture are not unheard of in Denmark, but they are very uncommon.

May have been reddish brown

A few years ago, a paddle was found in a kitchen midden at Flynderhage in Norsminde Fjord. The decoration on this paddle is reminiscent of that on especially one of the paddles from Horsens Fjord.

This paddle from Flynderhage has four narrow lines, curved in the middle, on a similarly solidly painted lower half. The only variation in the motives on these two paddles seems to be the number of lines.

The best-known patterned paddle blades, however, are those found in Tybrind Vig, where four out of the 13 paddle fragments that were found had different decorations.

These consist of ornate patterns of dots and lines crafted in a sharp-edged, incised relief, which has subsequently been shown to contain ochre-bearing black paint.

This indicates that the original colour may have been reddish brown. Ochre is a dye known from contemporary burials. So there are clear differences, in terms of both motive and technique, between the paddles found in Horsens Fjord and Tybrind Vig.

Patterns had symbolic meaning

The painted paddle blades bear witness to the decorations and colours which have undoubtedly been a regular part of everyday life in the Stone Age, but of which we only get the occasional glimpse.

Out of the many ornamented objects made from bones and antlers found in Horsens Fjord and elsewhere over the years, antler axes provide us with the clearest insight into this world of patterns.

At first glance the lines may appear random, but the engravings were not only meant as a visual embellishment; there’s no doubt that they had a symbolic meaning that made sense at that particular time and place.

Paddle decorations marked identities

In a hunter-gatherer society it was important, both internally and when meeting strangers, to signal a sense of community and affiliation to family or tribes.

This could be done with the clothing or perhaps with face paint. This, however, we have no way of documenting archaeologically.

The indispensable dugouts enabled the Ertebølle people to travel far and wide. They could even travel across ice in winter, so it was probably not uncommon for them to meet people of foreign origin.

In a world full of symbols it was therefore natural to be seen and understood through the decorations on one’s paddles.

We know little about the meaning

In today’s rowing clubs, it’s not uncommon to see oar blades in a variety of colours or symbols that identify the rowers’ nationality or club membership when the meet with other rowers.

Having only found a few patterned paddles, we cannot infer much about the meaning of the motives.

Since we’re seeing the same decoration on paddles from Horsens Fjord and Norsminde Fjord, it seems likely that they denote some sort of community, perhaps a clan affiliation between the populations by the two fjords.

If this is the case, there must have been a different relationship to the people at Tybrind Vig. Here, a highly different patterning with other designs indicates that we’re talking about a different tribe.

-----------------------------------------

This article is reproduced on this site by kind permission of Skalk, a Danish periodical with articles about Danish prehistoric and medieval archaeology, history and related topics.

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther