Treatment for blood poisoning can be fatal

A widespread treatment of severe blood poisoning can provoke life-threatening kidney failure and haemorrhages. The researchers behind a new study recommend that this treatment should be stopped.

Patients suffering from severe blood poisoning (sepsis) are usually treated with a drug called hydroxyethyl starch (HES).

A new study now shows that there is a significant risk associated with the drug. It can induce kidney failure and haemorrhages, which in the worst case can kill the patient.

The findings have been published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“Our results show that hydroxyethyl starch increases mortality rates by up to 17 percent in patients with severe sepsis, compared to treatment with a regular saline solution,” says Anders Perner, a professor at the Intensive Therapy Clinic at the Copenhagen University Hospital.

“This is a significantly increased risk, and the country’s intensive care units have stopped using this drug to treat sepsis.”

Starch vs saline

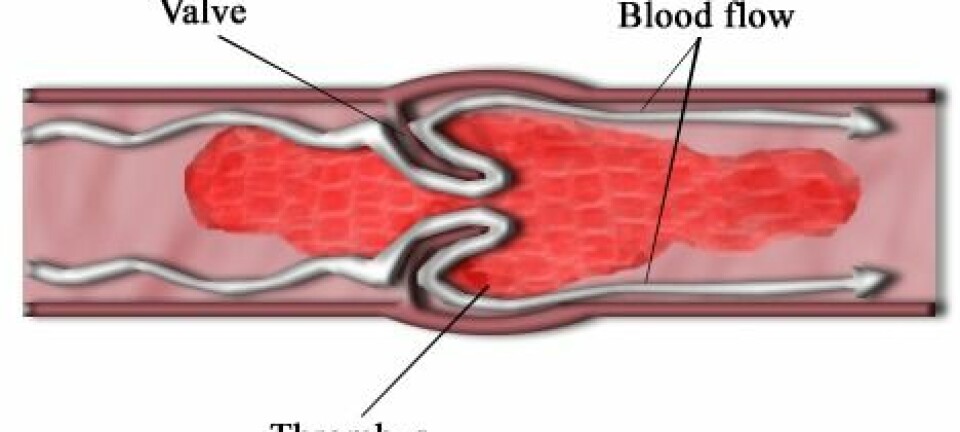

Sepsis is the term for a strong inflammatory reaction, triggered either by live bacteria or bacterial constituents in the blood, which may lead to circulatory failure.

Bacteria can enter the body via an object which is placed directly into the bloodstream – such as a tube inserted through the skin, or through the lymphatic system, for instance by stepping on a rusty nail.

The initial life-saving treatment focuses on stabilising the circulation. This can be done using two different fluids: starch or saline.

The new findings are pushing scientists’ view on which of the two treatments is best. Intensive care departments have so far been using both treatment forms; however, HES has been the preferred form as it was believed to stabilise the circulation.

“In recent years, however, concerns have been raised about the side effects of this drug, and that’s what we have examined in our study,” says Perner.

The study was an eye opener

The scientists have studied which effects and side effects the two types of fluid had on almost 800 patients with severe sepsis, who were hospitalised in 26 intensive care units across Scandinavia.

The results were clear: the two fluids’ ability to stabilise the circulation was identical.

As regards side effects, however, significantly more patients in the starch group developed kidney failure and required dialysis. These patients also had a greater number of haemorrhages which were so severe that the patients required blood transfusion.

“The study is an eye opener and it shows that starch should not be used in the treatment of sepsis,” says the professor.

“Most Danish intensive care units have already changed their practice because they have participated in the study, and the staff has seen with their own eyes which consequences the treatment can have. The impact of the findings is enormous. "

Should have consequences in developing countries

Perner believes there has already been a change of attitude in Denmark, so there is no real need for the authorities to intervene. But things are different elsewhere, not least in developing countries where severe sepsis is a common problem.

“Globally, severe sepsis is the most frequent cause of death. In Denmark alone, some 2,000 sepsis patients are admitted to intensive care units every year, half of whom die,” he says.

“HES is recommended worldwide as an important part in the battle against severe sepsis, so the challenge will consist of spreading this information internationally. So having our findings published in The New England Journal of Medicine is the best thing that could happen.

-----------------------------------------

Read this article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther