Toys contaminated with harmful bacteria

Harmful bacteria contaminate toys, cushions, sofas, tables and chairs in day-care institutions for children, making them ill. Maybe nanotechnology can help solve the problem.

Sick children keep parents off work until the child is well again – and children who are frequently ill are a big problem for society.

This has prompted Danish researchers to establish an innovation consortium called SIB to study how many children are infected by bacteria on the surfaces of toys and furniture at day-care institutions, and to find cleaning methods, so children will be less frequently ill in the future.

“There is a very high frequency of illness at these institutions and we want to reduce it,” says Tobias Ibfelt, a medical doctor and PhD student at the Copenhagen University Hospital’s Department of Infection Control.

“Many researchers have studied the direct line of infection between children – where the children infect each other through touch, coughing and so on. Reducing that type of infection is very expensive, as it almost always requires more space per child in the institution.”

The surfaces in these day-care institutions are clearly filthier than they should be – and this increases the risk of infection transfer and thus also the number of sick children.

Tobias Ibfelt

Ibfelt, one of three PhD students working with SIB, adds, “Our angle involves looking at typical surfaces in kindergartens, where the bacteria flourish, and see whether better cleaning solutions can reduce the number of sick days cheaply.”

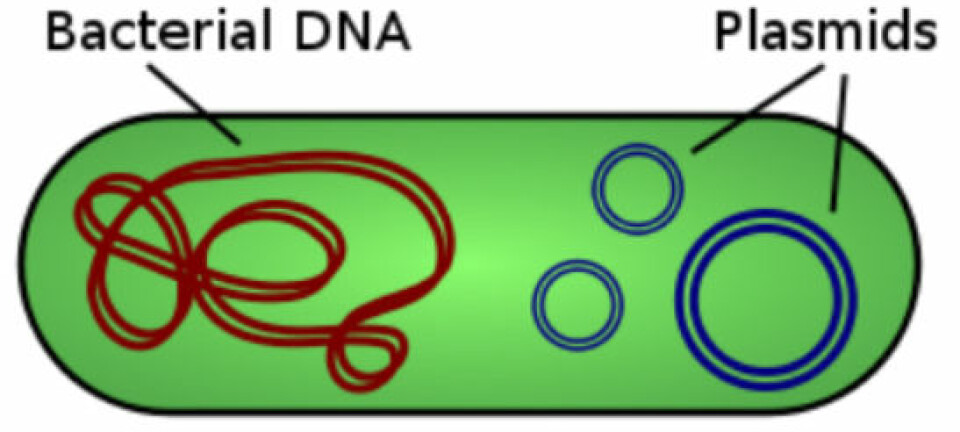

Toys with intestinal bacteria

The SIB project has three main purposes:

1. Identify the surfaces that are ‘hotspots’ for bacteria.

2. Find cleaning solutions that can reduce the number of bacteria on the surfaces.

Many researchers have studied the direct line of infection between children – where the children infect each other through touch, coughing and so on. Reducing that type of infection is very expensive, as it almost always requires more space per child in the institution.

Tobias Ibfelt

3. Find suitable cleaning methods that make it easier to keep treated surfaces free of bacteria.

Ibfelt’s team has spent the past few months collecting samples from a variety of surfaces at 24 day-care centres for children in Denmark. Bacteria prefer toys, cushions, nappy-changing tables and dining tables as their habitats.

The samples were primarily taken at crèches, as it is primarily the small children here – who often put items in their mouths – who are most at risk from indirect infections via toys or surfaces.

“Bacteria are everywhere, of course, so my task is to identify the bacteria that cause diseases among the many bacteria that are not harmful,” says Ibfelt.

“Our study hasn’t been completed yet, but the results so far show that there is bacterial pollution from excrements in 10 percent of our samples, and bacterial pollution from respiratory bacteria in 15 percent of the samples. The surfaces in these day-care institutions are clearly filthier than they should be – and this increases the risk of infection transfer and thus also the number of sick children.”

Thorough cleaning

Some of Ibfelt’s colleagues at SIB work with the cleaning teams at the day-care institutions to develop new cleaning standards. Dining tables are now cleaned before the children eat, and not solely after the meal. Nappy-changing tables are now cleaned more thoroughly and more frequently than before.

Thorough cleaning of dining and nappy-changing tables can give a significant reduction in the number of sick days.

“We hope to be able to reduce the number of sick days by about 10 percent simply by cleaning these tables more carefully than before,” says Ibfelt.

Nanotechnology in cushioned areas

The materials used in the institutions are also being studied thoroughly by, among others, PhD student Troels Eriksen of the Danish Building Research Institute, which is collaborating with Department of Physics and Nanotechnology at Aalborg University.

“My research comprises both studying whether there is any potential in reducing the number of infectious micro-organisms in day-care institutions by using surface-treatment methods and designing concrete treatment methods for this purpose,” says Eriksen.

He studies the many easily cleaned surfaces in the institutions – such as treated wooden surfaces – and the surfaces that are far tougher to clean. In this case, Eriksen investigates various surface treatment methods that may make cleaning them easier.

“The institutions have some things that are very difficult to keep clean,” he says. “These include textiles such as cushions and curtains. Here I am developing a surface treatment method that in practice will be in the form of a spray with nano-fibres that are either antimicrobial or bacteria-neutralising in another way, so the bacteria are no longer a threat to the children’s health.”

In addition, Eriksen is looking at a similar method to ease the cleaning of treated wooden surfaces.

“One of the great challenges of this process of course is developing methods that not only have the desired effects but are also harmless to children,” he says.

Solutions expected in 18 months

Improved cleaning methods are regarded as the viable path in terms of reducing the number of sick days for children at day-care centres.

Eriksen and Ibfelt are sure that targeting cleaning – concentrating on surfaces where there are most bacteria, and changing surfaces so they are easier to clean – can lead to a significant reduction in the number of sick days among children, and thus keep parents and grandparents at work.

SIB expects to present its final proposals in 18 months’ time.

------------------------------

Read this story in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Michael de Laine