Scientists: football has changed dramatically

New research on the Premier League shows that professional football players are sprinting more and more. And it is changing the way the game is played, say scientists.

If you are a football fan, you might have noticed that European league games have changed over the years, and that player activity in most games can vary wildly in intensity.

Sometimes there will be bouts of 10 to 15 minutes of action-packed fights for the ball with lots of goal attempts--but other times, it might feel like the players are still on half-time. Compare this to games in the 1980s where the intensity would remain more or less constant throughout the entire game.

Science can now back up that claim. A new study shows that the amount of sprinting in the English Premier League has increased by 50 per cent in ten years.

The new research is based on the analysis of 473 Premier League players, and shows that the high intensity sprints come at a price: after just a couple of minutes of sprinting, the players will have a hard time keeping up with the game for upwards five minutes.

Faster pace and more sprinting in professional football

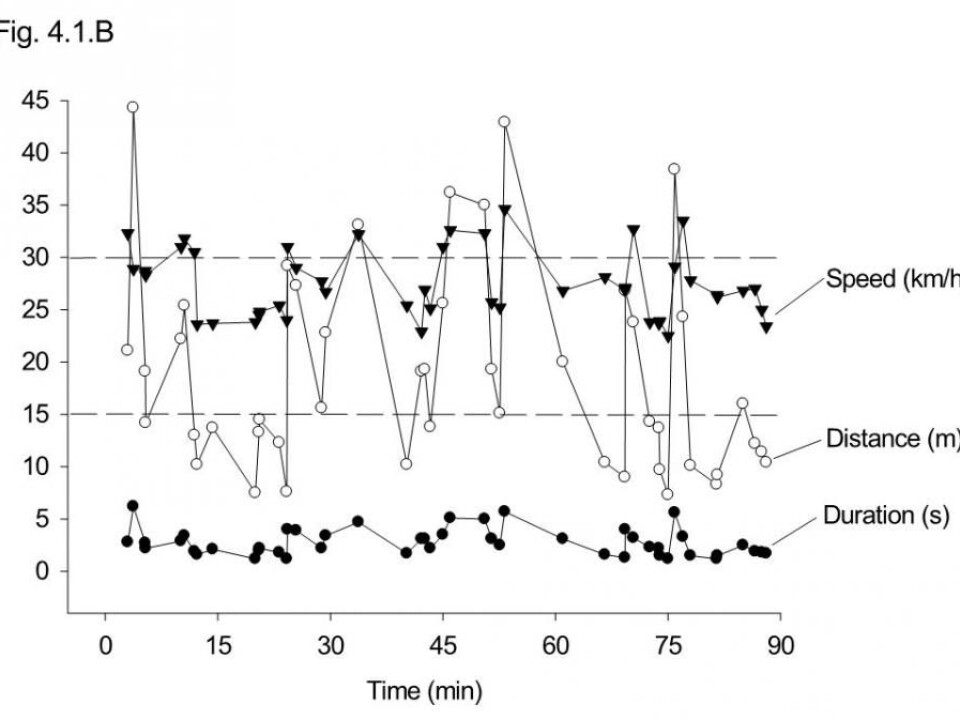

The new study sheds light on why modern football games often appear as if they are jumping between two extremes, either high intensity or near complete standstill.

“The general pacing of football has increased dramatically and it seems as if the nearly constant intensity of the game, which was characteristic of the sport a couple of years back, has been replaced with a lot of high intensity sprinting periods followed by resting periods,” says co-author Magni Mohr from the University of the Faroe Islands.

The study shows that a mere minute of repeated sprinting at the onset of the game will cause the players to temporarily tire.

“That’s pretty interesting because it has implications for how we should be training football players,” says Mohr.

New study is a milestone in football research

Mohr studied and analysed player behaviour in a sample of Premier League games between 2010 and 2012.

The study shows that a permanent state of tiredness sets in among the top players in the final 20 to 25 minutes of the game.

This suggests that there is a lot to gain--at least on the running front--from player substitutions during the second half of the match, says co-author Professor Peter Krustrup from the University of Southern Denmark.

“Modern football is currently experiencing a trend of a lot of goals being scored in the final fifteen minutes of the game,” says Krustrup, pointing to the recent UEFA Euro 2016 tournament where 26 per cent of all goals were made after 75 minutes of playtime.

The new study is published in the scientific journal Science and Medicine in Football.

New research could affect football training

Jesper Løvind Andersen, head of the Institute of Sports Medicine Copenhagen at Bispebjerg Hospital, calls the new research impressive and in line with previous studies on the subject.

“It’s an incredible data source and it’ll probably become the go-to study when it comes to this topic,” he says. “I use this kind of research when I teach football coaches and try to explain that certain playing styles comes with certain expenses.”

If you are going for an aggressive playing style with lots of high intensity running to pressure the opponent, then it is necessary to tailor training sessions to counter the offsets attributed with such playing style.

“That’s important to know for both coach and player so they are better able to counter periods of tiredness,” says Andersen.

He suggests that football training needs to be re-thought and focus more on anaerobic exercises to help prepare the players for the high intensity sprinting demanded by modern football.

Focus on the high intensity periods of the game

Mohr was a physical trainer in Chelsea F.C. from 2008 to 2011. Based on his experiences there, he says the new results should have “high usability” in the real world.

“I think one of the things to take from this is that we need to focus on the most important sequences of the match and not just the total of it,” he says.

“When you watch Champions League you are often told players ran nine kilometres or ten kilometres during the game. That doesn’t matter. It’s completely irrelevant. It’s much more important to look at how players performed during the high intensity periods that defined the game,” says Mohr.

Krustrup is currently in Manchester to present the study results to the coaches and players in Manchester City. Back in Denmark he is part of the newly established research unit for Sport and Health Science at the University of Southern Denmark. One of the goals of the research unit is to help spread scientific knowledge of training and strategy to professional football clubs.

--------------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex

Scientific links

- Running intensity fluctuations indicate temporary performance decrement in top-class football, Science and Medicine in Football, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1254808

- Evolution of match performance parameters for various playing positions in the English Premier League, Human Movement Science, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2014.10.003

- Match performance of high-standard soccer players with special reference to development of fatigue, Journal of Sports Sciences, DOI: 10.1080/0264041031000071182