Rising temperatures could destroy Greenland's archaeological treasures

Climate changes on Greenland are currently threatening areas of archaeological importance that have not yet been excavated. Therefore, The National Museums of Denmark and Greenland have started several projects where decomposing wooden artifacts and bones will help identify the areas, which are most seriously threatened — and save them.

There is an increasing risk that wooden and bone implements from the first people on Greenland will be consumed by the sea, destroyed by fungi or pierced by willow scrub roots in the future. This is partly happening, because the average temperature has risen by two to three degrees.

To secure the many archaeological finds, which have not yet been excavated, the National Museums of Denmark and Greenland have started a new project that, among other things, will result in an interactive map showing which places are most threatened by future climate change.

"To safeguard the more than 6,000 archaeological sites on Greenland, it is important that we map the threats and find the places, where the situation is worst," says Jørgen Hollesen, senior researcher in geography at the National Museum of Denmark's Conservation department. "The ultimate aim is a tool that can give us an idea of where to focus first."

The threats come from land, water and air

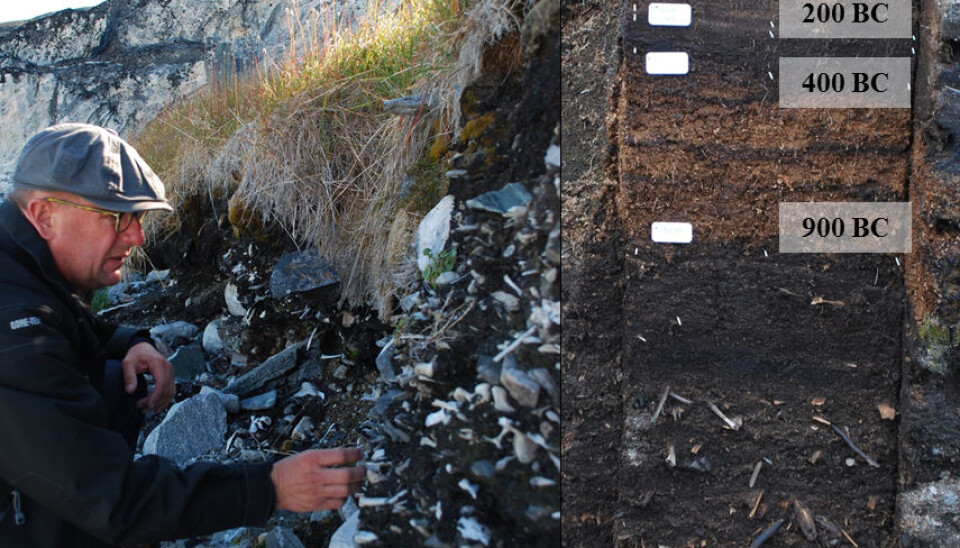

Among other things, it is the many kitchen middens from the early settlers on Greenland, that researchers, archaeologists and the Greenland National Museum and Archives are interested in preserving, as they give insight into the conditions of life throughout thousands of years.

The greatest problem is the rising temperature. This leads to:

- Thawing of the protective permafrost. This thawing leads to the archaeological material rotting, especially if the soil dries out afterwards. When this happens, the amount of oxygen rises and the decomposition processes accelerate.

- Melting water from snowdrifts can wash protective layers of soil away from the kitchen middens.

- Willow scrub and other plants grow on the kitchen middens, because the soil contains nutrients.

- Rising water levels wash the kitchen middens into the sea.

"The purpose of the project is to find out what the threats are," says Henning Matthiesen, a senior researcher at the Conservation department. "For example, in these northern parts of Greenland, we have not yet found fungi that decompose wood. These fungi are currently only found in southern areas, and the question is whether they will gradually migrate northwards in line with climate changes. That's just one of the threats that must be assessed."

Qajaa's deep-freezer might melt

One of the places, where the scientists have conducted their studies, is in western Greenland, at Qajaa. Here lies one of the best-preserved settlements, a time capsule in the permafrost, going back more than 4,000 years.

Here the scientists have drilled for and extracted specimens, which they have analysed and carried out oxygen consumption tests on.

"Qajaa is extremely valuable as it is one of the very best preserved settlements," says Matthiesen. "It's been known since 1870, but most of it remains unexcavated. It will be necessary to excavate it if it becomes threatened — for instance, if we can see suddenly foresee that it will be gone in ten years' time."

Although the permafrost, which works as a deep-freezer, presently preserves Qajaa, is it likely that the rising temperatures will become a problem in the long-run.

"If the temperature changes continue, it will be threatened," says Hollesen and adds "Our models predicts that the frozen archaeological layers will start to thaw in 2050 – and that is a big problem."

A freezer full of bones

To find out which conditions are the most threatening for the ancient archaeological treasures, the scientists have taken specimens from several kitchen middens on Greenland and measured the oxygen consumption of the various finds. "For instance, We have study the oxygen consumption of a piece of wood from a tree. When bacteria and fungi decomposes wood, they use oxygen. If we can measure how quickly the oxygen disappears, then we have a strong indicator, of how soon the tree will disappear.” explains Matthiesen.

At the National Museum of Denmark's Conservation department there are several freezers full of wood from trees, bones and other things from Greenland, which the scientists have been allowed to study. Hollesen explains, that organic matter found in the permafrost decomposes quite quickly, and must therefore be kept under the same cold conditions, that they came from.

"If we let this piece of wood from a tree lie here at room temperature, its rate of decomposition will rise by two to four times every time the temperature rises by ten degrees," he says. "In fact, decomposition of organic material will be even quicker here in Denmark, because we have a lot of fungi-spores in the air."

More measurements provide a better scale

The purpose of measuring oxygen consumption is to give the scientists an overview of how materials such as wood, bone and metal decompose under different temperatures and moisture conditions.

By taking hundreds of samples, it will become possible to create a scale, that shows how quickly various materials decompose, and thereby find out how soon the archaeological areas will lose their organic content.

The many measurements are to be stored in a geographic information system and combined with maps over future soil temperatures, moisture conditions, plant distribution and the risk of coastal erosion. In this way, scientists in the future will be able to use the interactive map to see which threats are the worst in which areas.

”When we've gone a bit further with the project, it won't be necessary to take large specimens from all sites," says Matthiesen "we will be able to make do with a few samples from new archaeological sites, and use the scale to know, whether any given location is in a risk zone."

Greenland cannot excavate everything by itself

According to Hollesen and Matthiesen, Greenland really needs a tool to give a better overview of the locations of the archaeological sites and their conditions. A database with information on some of the areas exists already, but the information is not systematised.

"The Greenland National Museum and Archives receives many approaches from researchers who want to carry out excavations on Greenland. The museum would like to have a tool, that can be used, to direct excavations to threatened sites, that are expected to disappear in the near future," says Matthiesen. "They do not have the resources to excavate all of these sites by themselves".

"It's not a question of whether climate is changing or not," Hollesen says. "The consequences can be seen quite clearly today — and that's why we have to act now."

You can read more here about some of the projects at Qajaa. The article is in Danish, but a summary and the captions are in English.

Scientific links

- Degradation of Archaeological Wood Under Freezing and Thawing Conditions—Effects of Permafrost and Climate Change, 2013, DOI: 10.1111/arcm.12023

- Paleo-Eskimo kitchen midden preservation in permafrost under future climate conditions at Qajaa, West Greenland, 2011, DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2011.01.011

- The Future Preservation of a Permanently Frozen Kitchen Midden in Western Greenland, 2012, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/1350503312Z.00000000013