Researchers sow doubt about Moon's origins

New dating of Moon rock pulls out the carpet from under the prevailing theory about how our Moon came into being. Either the Moon is younger than previously thought – or it was not born of a red hot sea of magma.

How was the Moon created?

Scientists thought they had a sound answer to this question, but a Danish study now indicates that something was very wrong with their theory.

The results of the study by geochemists at Copenhagen's Natural History Museum have just been published in the esteemed American science journal Nature.

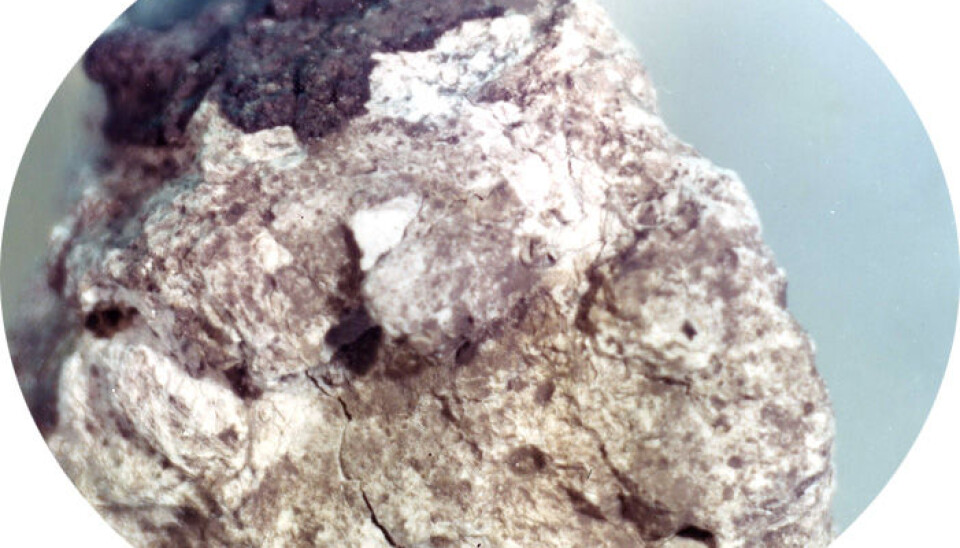

The researchers have dated lunar rock from the surface of the Moon using two improved dating techniques. Both techniques conclude that the rock is about 4.36 billion years old, considerably younger than previous datings of between 4.44 and 4.567 billion years.

The new dating is not consistent with our theories as to how the Moon was created. It indicates that the time has come to re-evaluate our model for the creation of the Moon.

James Connelly

"The new dating is not consistent with our theories as to how the Moon was created," says senior lecturer James Connelly of the Natural History Museum, who led the study. "This indicates that the time has come to re-evaluate our model for the creation of the Moon."

The theory provides no plausible explanation

According to the prevalent theory, the giant impact hypothesis, the Moon was formed during a collision with our newly born Earth and a planet-like object which happened to pass by during the evolution of our solar system some 4.567 billion years ago.

The collision smashed thousands of splinters off the Earth into space, where they rapidly clumped together into a giant ball of dust. This clumping released a huge amount of energy which heated up the ball, melting its surface into one giant sea of magma several hundred metres thick.

As the Moon gradually cooled down, various minerals began to precipitate and solidify. The lightest minerals precipitated first and floated around in the magma surface, transforming over time to form the mantle. The heavier minerals did not settle until later, forming the foundation of the lunar crust.

The new study is based on the assumption that the collected lunar rock was created when the Moon's surface began to solidify and that they therefore can be used to date the Earth.

But this theory is not compatible with the new datings:

"We know how long a sea of magma takes to cool down and it does not fit in with the new datings," says Connelly.

Old dating methods no good

The discrepancy has led the researchers to wonder whether the sea of magma ever existed at all. The lunar rocks they have dated does have a chemical composition that corresponds to what one would expect if they were the first rocks to precipitate from the sea of magma, but this is not adequate documentation to prove that the theory is correct.

"We are still looking for an explanation of the rocks' relatively young age. Perhaps they don't have their origins in a sea of magma, or they may have been mixed up over time with younger material from, for example, meteorites or volcanic eruptions. In that case they cannot be used to date the Moon as we have believed up to now."

Although the new study asks more questions than it answers, it still managed to slip through the eye of Nature's needle, and according to Connelly there is a good reason for this.

"As the first team ever, we have succeeded in achieving the same dating of lunar rocks using two different and improved dating methods. Previous attempts at dating the rocks have produced a great variety of results. Now we finally have an unambiguous age which we can use to test and further develop our models," Connelly concludes.

Read the article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Scientific links

External links

- Lunar samples on the Lunar and Planetary Institute website

- James Norman Connelly's profile

- About the Giant impact hypothesis (Wikipedia)