Organic tools found in Stone Age camp

Sensational new archaeological find reveals paddles and bow in underwater Stone Age settlement

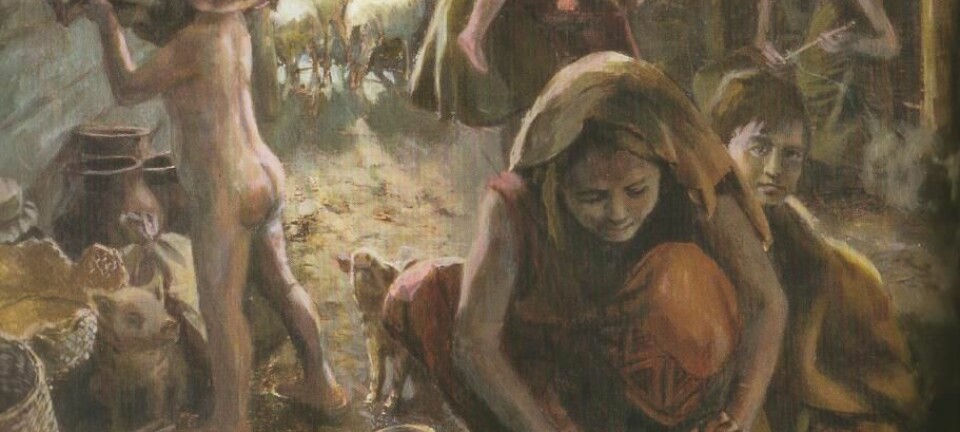

Stone Age people didn't only use tools made out of rock – they also used tools made from wood and antlers, according to a new discovery in Danish waters.

The Stone Age settlement has been hidden under water and a thick layer of sand over millennia. But over the past few years, sea currents have exposed it by pushing the seabed aside.

Settlement known for decades

The village lies deep underwater by the coast in Horsens Fjord, Denmark.

Archaeologists have known about the site since the '70s, but due to the inaccessibility, it wasn't until a recent trip to the site by an archaeology student at Aarhus University that something started to stir.

Peter Alstrup went to his nearby beach to trace old footsteps from when he used to go to the beach with his parents. As part of his frequent swims along the coast back then, he had built himself a glass box through which he could study the seabed in great detail from the surface.

He had heard about an area where a Stone Age village was supposed to be buried. He often visited this area and found flint flakes from ancient times, and this is what made him want to go on and become an archaeologist.

Revisiting the underwater playground

More than a decade later, in the summer of 2010, Astrup went back to the beach, this time wearing a diving suit.

He noticed straight away that the seabed looked different, with most of the sand vanished from the subsurface. This enabled him to spot some beautifully shaped pieces of wood, which at some point had clearly been crafted by humans.

“As soon as I got home, I called up my local museum to tell them about what I had found. We agreed that I should go down and pick up few items and bring them in,” says Astrup, who is currently a PhD student of archaeology at Aarhus University.

He brought back with him undamaged antler axes, wooden knife handles and the skull of a dog.

When the archaeologists at the museum saw this, they realised they had run into something unique. They quickly assembled a group of archaeologists from the area who rushed into their digging.

Ideal location for excavation site

In many ways the area is ideally placed for archaeological excavation. Located just off the coast, it's neatly hidden away from all beach activities. But since it lies in shallow waters, excavation is relatively easy, regardless of whether the archaeologists wish to dig into the underground, chart the area or simply pick up objects from the bottom of the sea.

They looked specifically in a certain sediment layer under the sand, characterised by its low oxygen levels and its ability to preserve organic materials.

Here they found objects that revealed an industrious community of hunter-gatherers. These included beautifully ornamented antler axes with well-preserved wooden shafts and a highly surprising find of a pair of wooden rowing paddles, richly decorated with black patterns.

Anoxic sediment preserves wood

The archaeologists also found a 1.6-metre high wooden bow of a hitherto unknown type. These bows have probably been used some 6,000 years ago, when large parts of Denmark were covered in woods, making it an ideal hunting ground.

In addition, they also found a piece of string made out of bast fibres, which was as thick as a woollen thread. These strings are thought to have been used for frapping tools.

Excavation leader Claus Skriver of the Moesgård Museum explains what makes these finds so special:

“When we excavate settlements on land we only find tools of stone, since all organic matter has long since rotted away. This settlement is unique because we also found well-preserved objects made out of wood and antlers, and that gives a much more nuanced insight into how people lived back then.”

Seasonal or permanent residence?

The excavation can also help the researchers find answers to some great questions such as whether the settlement was being used throughout the year or whether it was a seasonal dwelling place where people lived over certain periods of the year.

The archaeologists found the answer looking through their bore holes through the organic silt. Here they found an abundance of fish bones, which are remnants from the residents’ meals. They also found well-preserved seeds and hazelnut shells.

There are examples of Stone Age people moving into certain sites when, for instance, fishing prospects looked good, when it was colder than usual or when the surrounding woods were crowded with herds of animals.

“With all these bones, we can now outline in detail what these people lived on and also which periods of the year they lived there,” says Skriver.

Specifying which parts of the year the site was inhabited is a demanding task, but the new finds make it relatively easy to date the village.

“We’re trying our hardest to date the settlement using the Carbon-14 method,” says the researcher. “But the design of the site suggests that it’s from the middle or late Ertebølle period [see factbox]. The oldest section of the site was habited some 6,700 years ago.”

A sea of objects left to explore

The excavations are currently limited to only a few square metres of seabed.

Most of the objects discovered so far have come loose from the subsurface as a result of ocean currents. This means that the archaeologists manage to find new and exciting objects every time they visit the site.

The objects need to be picked up carefully. Wood that has been in water for long periods has had all its cell membranes dissolved. So when the wood dries up, there is nothing left to hold it together, and after only a few hours in dry air, the wood starts to crumble and fall apart.

Settlement known internationally

Peter Alstrup has taken part in all the excavations so far and is excited about the next visit to the site:

“The settlement is no longer something I can keep to myself – now I’m just happy to share it with others,” he says.

“Thanks to our excavations, this site has now entered the top 10 list of the best archaeological finds in Denmark in 2011 and is already a much discussed topic in international archaeological circles.”

--------------------------------------------------

Read this article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther