New satellite will test Einstein’s theory

A new satellite is launched that will test Einstein's general theory of relativity. Alongside it is a miniature satellite, designed and built by students to monitor shipping around Greenland.

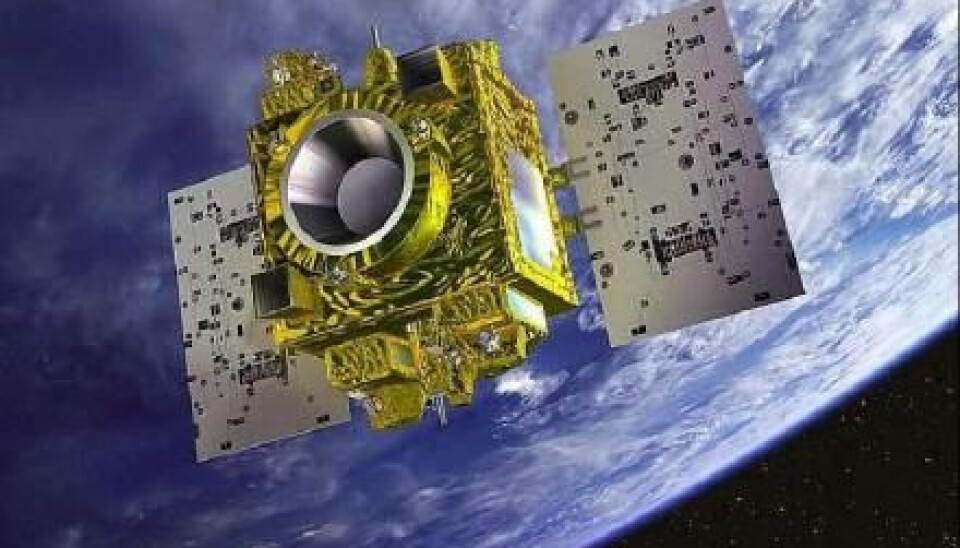

The French satellite, Microscope, was launched successfully on 25 April 2016 with the mission of testing the so-called equivalence principle in Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

This describes how people in free fall do not feel their own weight and is what ultimately led Einstein towards his theory of general relativity that states that gravity is not a real force.

The equivalence principle is central in Einstein’s general theory of relativity, and without it, the theory faces real problems.

New technology is 50 times more accurate

Staff at the Institute of space research and technology at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU Space) are happy to see the satellite launch.

They developed some of the tools onboard--new cameras to help orient the satellite with unprecedented accuracy, says Professor John Leif Jørgensen, who has been with the project since 2004.

"We have delivered two ultra-precise star cameras, which makes it possible to measure the satellite's orientation with an accuracy of 20 thousandths of a second of arc [a measure for calculating angles]--50 times better than any other spacecraft," says Jørgensen.

A sensation if Einstein got it wrong

Einstein's general theory of relativity states that gravity is not a force. What we perceive as gravity is actually a curvature of space-time, caused by objects like the Earth.

The vast majority of physicists expect that the experiment will confirm that Einstein was right--just like the countless of other experiments in the past 100 years.

But if the satellite shows that general relativity is not the whole truth, then the Microscope could lead them towards a new theory of everything--which could be equally exciting.

Unexpected results could help physicists to reconcile the two great theories of physics in the 20th century: quantum mechanics and relativity.

This would bring them a step closer to learning the truth about the nature of the universe.

Student designed satellites also launched

Microscope was one of five satellites launched on a Soyuz rocket from Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. Also onboard was the large European Earth Observation Satellite Sentinel-1B, which is the partner of Sentinel-1A that launched in 2014, and three small CubeSat satellites.

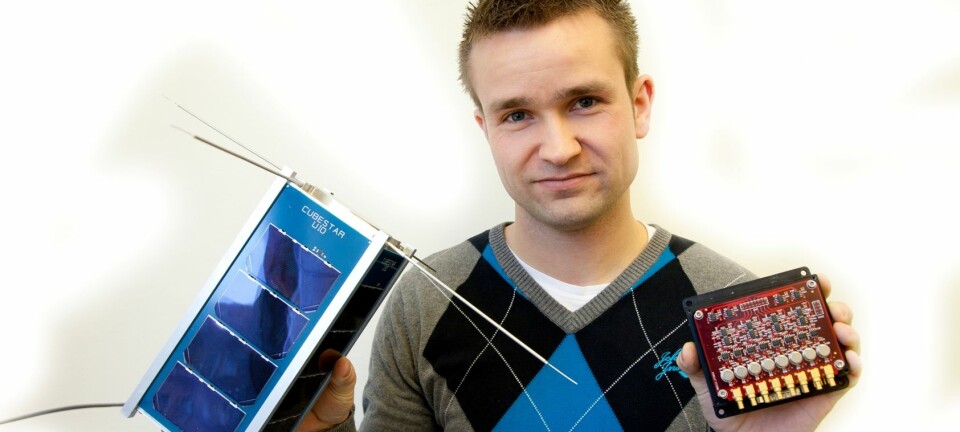

These miniature CubeSats measure just ten by ten centimeters and were designed and built by students as part of the European Space Agency’s ‘Fly Your Satellite!’ program.

One of the CubeSats--AAUSAT4--was designed and built by students from Aalborg University, Denmark, and will collect and transmit data on shipping traffic around Greenland.

Watch students from Aalborg University in Denmark explain what their small satellite will do in space. (Video: ESA)

-------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex