New record: World’s oldest animal is 507 years old

It’s time to rewrite the record books. New accurate dating shows that the world’s oldest animal was 507 years old when it died in 2006. That’s more than 100 years older than previously thought.

In autumn 2006 a team of researchers went on an expedition to Iceland, where they discovered something that made the headlines across the world. The discovery even made it into the Guinness Book of World Records.

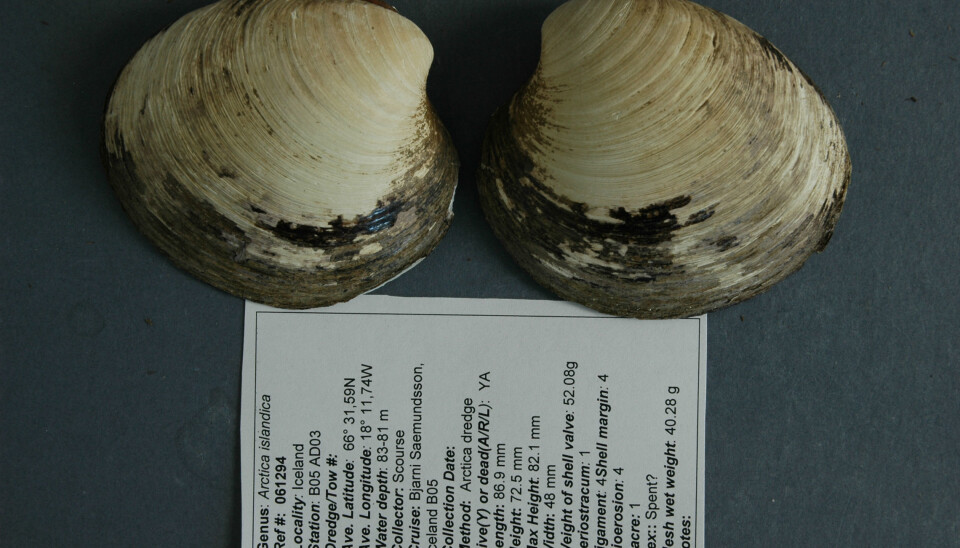

One of the Arctica islandica bivalve molluscs, also known as ocean quahogs, that the researchers picked up from the Icelandic seabed turned out to be around 405 years old, and thus the world’s oldest animal.

However, after taking a closer look at the old mollusc using more refined methods, the researchers found that the animal is actually 100 years older than they thought. The new estimate says that the mollusc is actually 507 years old:

“We got it wrong the first time and maybe we were a bit hastingly publishing our findings back then. But we are absolutely certain that we’ve got the right age now,” ocean scientist Paul Butler, who researches into the A. islandica at Bangor University in Wales, tells ScienceNordic.

A contemporary of Columbus and Luther

The ‘new’ age means that the mollusc was born in 1499 – only a few years after Columbus visited America for the first time, and more than a decade before Martin Luther’s Reformation of the Catholic Church.

The mollusc’s 507-year-long life came to an abrupt end in 2006 when the British researchers – unaware of the animal’s impressive age – froze the mollusc onboard the ship.

After its death, the mollusc was given the name Ming – after the Chinese Ming dynasty, which was in power when the animal was born.

Although Ming has turned out to be a full century older than first thought, the name is still relevant, as the Ming dynasty lasted for almost 300 years (1368-1644).

Did they get the age right this time?

How can we be sure that the British researchers have determined Ming’s correct age this time around?

According to one of the world’s leading mollusc researchers, there is a general agreement within research circles that 507 years is Ming’s correct age:

“The age has been confirmed with a variety of methods, including geochemical methods such as the carbon-14 method. So I am very confident that they have now determined the right age. If there is any error, it can only be one or two years,” says marine biologist Rob Witbaard of the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, who has researched into the A. islandica for more than 30 years.

Witbaard was not involved in the study of Ming, but he has read the new article.

We got it wrong the first time and maybe we were a bit hastingly publishing our findings back then. But we are absolutely certain that we’ve got the right age now.

Paul Butler

Bivalves were once thought not to exceed 100 years.

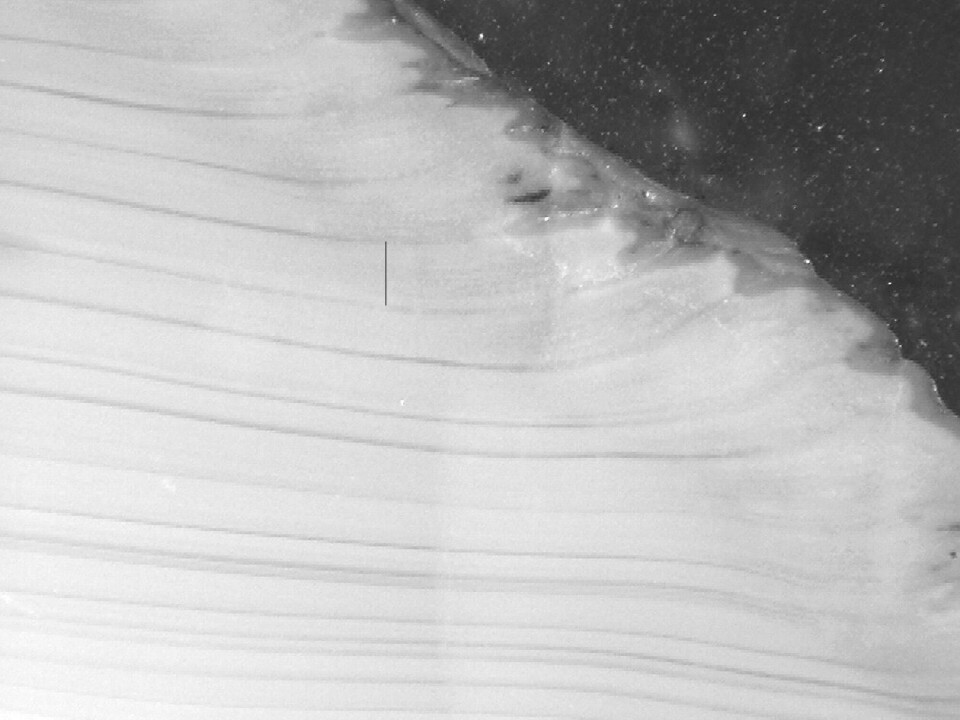

In the late 1980s, Witbaard was one of the scientists who discovered that the age of the A. islandica can be determined by counting growth rings in the shell.

“When I began my research in the 1980s, scientists didn’t know that the A. islandica could live beyond 100 years,” he says.

“I had several specimens in my collection that had more than 100 growth rings, but I found it difficult to convince people that they were really that old. Today, however, these growth rings have become an accepted way of dating the A. islandica.”

Why the initial misdating?

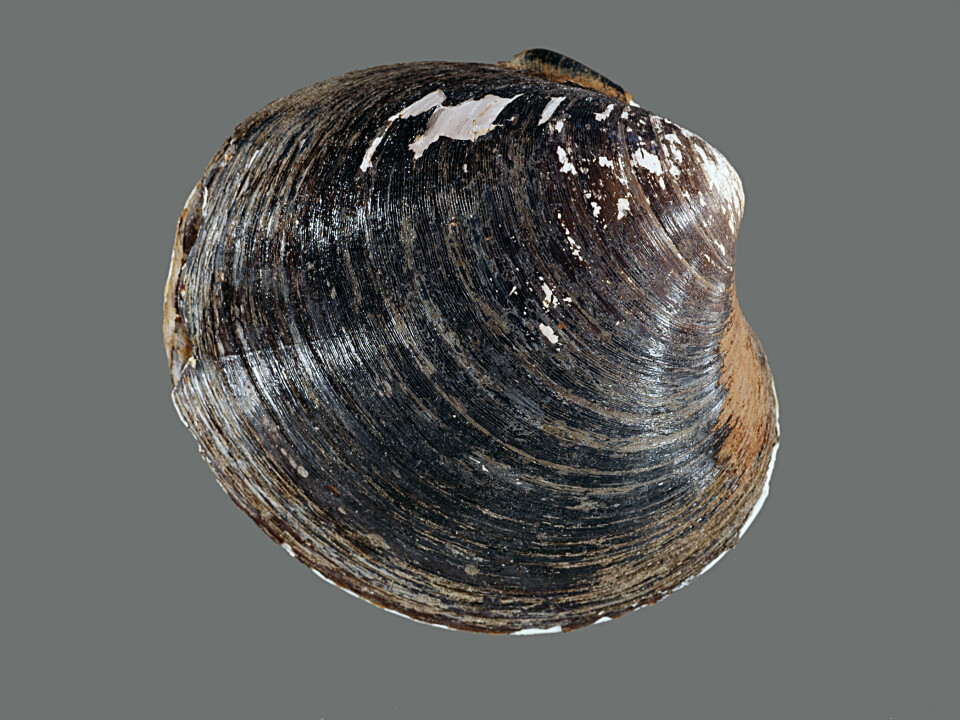

The growth rings on the A. islandica are visible both on the outside and the outside of the shell. The hinge ligaments that connect the two shells are generally considered to be the best place for counting growth rings.

“On the outside, the mollusc shell is curved, and that makes it difficult to get the right angle for measuring and counting the growth rings,” says Butler. “The growth rings are also better protected inside the hinge ligaments.”

And it was for this very reason that he and his colleagues initially chose to count Ming’s growth rings inside the hinge ligaments.

The problem with this, however, was that Ming was so old that the growth rings had become too compressed – the more than 500 rings were packed into a tiny hinge ligament area measuring only a few millimetres.

Unique patterns in growth rings

When the researchers started to re-date Ming, they therefore decided to look at the growth rings on the outside of the shell, as these were spread over a much wider surface and were thus easier to see.

And here they suddenly noticed many more growth rings.

To be extra sure, the British researchers began comparing Ming with other old specimens of the A. islandica.

According to Butler, different time periods are represented as unique patterns in the growth rings of the A. islandica – patterns that are almost identical in all specimens that have lived in the same area at the same time.

“In this way we can use measurements of other shells to determine that we actually arrived at the right age. The ocean quahog specimens we used for comparison were obviously not as old as Ming, but they have lived in different periods of Ming’s life. So this is how the patterns in their growth rings can help verify the age.”

Ming provides insight into climate changes

“The fact alone that we got our hands on an animal that’s 507 years old is incredibly fascinating, but the really exciting thing is of course everything we can learn from studying the mollusc,” says the head of the AMS 14C Dating Centre at Aarhus University, Denmark, Associate Professor Jan Heinemeier, who helped with the new dating of Ming.

The pattern in Ming’s growth rings does not only provide scientists with an accurate age of the animal; the A. islandica can also provide a unique insight into past climate conditions.

By examining the various oxygen isotopes in the growth rings, scientists can determine the sea temperature at the time when the shell came into being.

“The A. islandica provides us with a year-by-year timeline of the ocean temperature. I find that incredibly fascinating,” says Butler.

Rob Witbaard agrees that old ocean quahogs like Ming are a unique tool for shedding light on past climate change:

“There are a number of methods to chart past climate on land, but for the marine environment we only have some very limited data. The A. islandica can help fill this gap in our knowledge and provide us with a very accurate picture of past climate,” he says.

“This is important to our understanding of how much changes in the oceans affect the climate on land. And the really amazing thing is that the pattern in the ocean quahog’s growth rings actually recurs in tree rings.”

What is Ming’s secret for longevity?

The discovery of Ming in 2006 has inspired many researchers to try and figure out the secret behind its impressive age.

One leading researcher in this field is the German animal physiologist and marine biologist Doris Abele. She believes that the ocean quahog’s ability to live for centuries is primarily due to a slow metabolism. The animal lives its life in slow motion, so to speak:

“The A. islandica has a very low oxygen consumption. When an animal has such a slow metabolism, it normally also means that it has a very long lifespan. However, I also believe that part of the reason for its longevity lies in its genes,” says Abele, who heads a research group for stress physiology and ageing in marine ectotherms at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany.

Ming may not even be the world’s oldest

Although the latest research has established that Ming is 100 years older than originally thought, it is still not certain that Ming is the rightful owner of the title as the world’s oldest animal.

If the world of primitive organisms is to be included in what we call ‘the animal kingdom’, then the so-called primitive metazoans – a collective term for sponge-like animals, cnidarians, and worms – include a species that beats Ming by thousands of years.

The glass sponge (Hexactinellida) is thought to reach an age of 15,000 years, and some researchers even believe they have found specimens with ages of up to 23,000 years.

--------------------------

Editor’s note: this article was updated 29 November after Paul Butler pointed out that he, at the first reading of this article, failed to notice the following error: Ming did not, as initially reported, die as a result of the researchers opening up its shell. The animal died when it was frozen onboard the ship. The shells were separated much later.

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther

Scientific links

External links

- Paul Butler’s profile

- Rob Witbaard’s profile

- Jan Heinemeier’s profile

- The AMS 14C Dating Centre at Aarhus University