New discovery could rewrite Viking fortresses’ history

Pottery shards question conventional understanding of Denmark’s Viking ring fortresses.

While most archaeologists and historians can agree that Denmark’s five Viking ring fortresses were most likely built by Harold Bluetooth around 980 CE, they remain divided regarding their purpose.

Was it to defend the kingdom? A demonstration of power? Or to cement the Christianisation of the Danes?

Many archaeologists think that the fortresses were built with just one goal in mind, and then disappeared more or less as fast as they had appeared in the first place.

But newly discovered pieces of ceramic pottery found in the main gates of Denmark’s fifth Viking ring fortress, “Borgring,” are now challenging this theory.

The pottery belongs to the first half of the 11th century, which puts it well after the assumed construction of the fortress. Shards of the same type of pottery were discovered in 2016 at the fortress’ eastern gate.

The discovery of ceramics at the north gate suggests that last year’s discovery was not a random find, says excavation leader Nanna Holm who also works as a museum curator at the Museum of Southeast Denmark.

It also suggests that the fortresses served different purposes over time, says Nanna Holm who is leading the excavation.

“We need to be open to the possibility that the ring fortresses were not just built to only remain for a short time, and then disappear completely afterwards. I think that the fortresses are more nuanced than that,” she says.

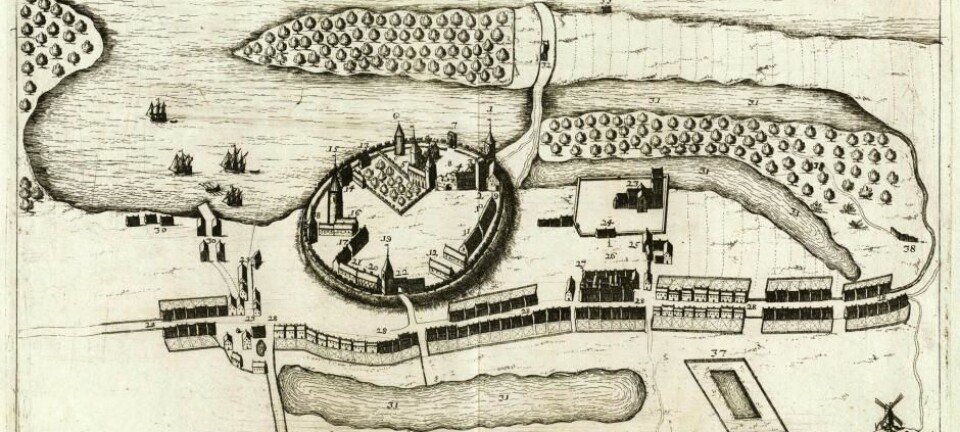

3D animation of the Viking ring fortress “Borgring.” The video was made in 2014 and a number of discoveries have been made since then and the houses shown in the animation have not been found on site. (Video: Archaeological IT Aarhus University)

An afterlife at both gates

“I love it when we discover things that help make the story fit into place. This suggests that the fortresses did not necessarily disappear when they’d achieved their intended goal—and this is a great story,” says Holm

Both the east and north gate appear to have partially burnt down, but the ceramics were found in soils that date after these fires—meaning that someone brought the ceramics into the gates after the fire. The ceramics at the north gate are situated in soil layers of the same age as those at the east gate, indicating that both sites were occupied simultaneously.

In the east gate, archaeologists also found floor layers, a fireplace, and a Viking toolbox in connection with the pottery.

This probably means that the gates did not burn down completely, and that some parts of the buildings at least partially remained for people to move into.

“Activity at one gate could just mean that it didn’t collapse completely after the fire. Now we find that the north gate was also used in the same period, and that suggests that you could still use the gates,” says Holm.

Few similar finds in Denmark

The pottery is strongly inspired by an English style known as Stamford Ware, and dates back to the first half of the 11th century.

There are only a few known examples of this type of ceramic outside England during this period, and it only shows up in the Viking political power hubs of Lejre and Roskilde in Denmark and Lund in Sweden.

The discovery surprises archaeologist and Stamford Ware expert Jesper Langkilde, a museum curator at Roskilde Museum, Denmark. He was not involved in the excavations at “Borgring.”

“It’s exciting because we only know of a few examples of this type of ceramics from Denmark and Skåne [in Sweden]. It shows that there was activity at ‘Borgring’ at the beginning of the 11th century, and it also suggests that this activity was something significant,” says Langkilde.

“This type of pottery has been associated with Knud the Great and his close relations to England, so we should perhaps think of this as something that signifies a royal presence or at least some higher social status,” he says.

-------------------

Read more in the Danish version on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex