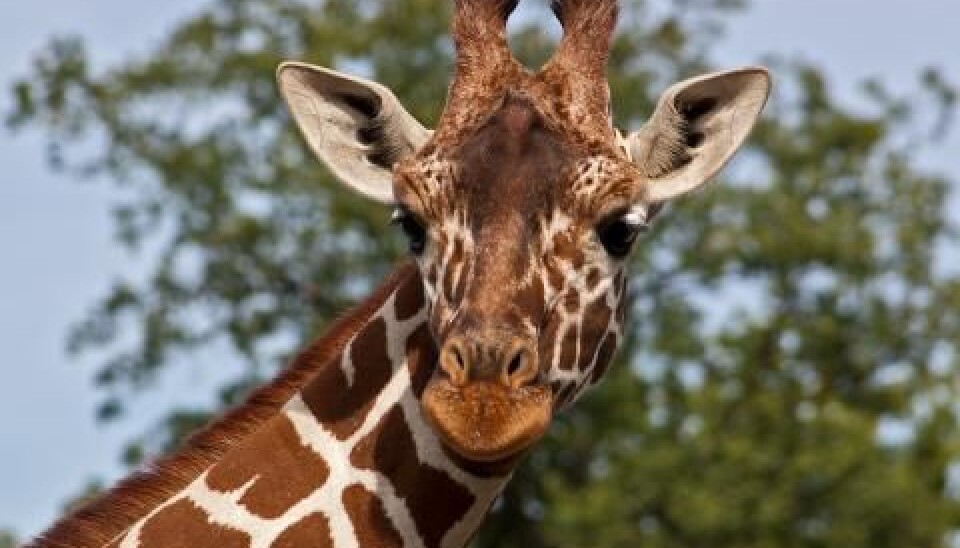

Marius the giraffe: He died so that others could live

The Copenhagen Zoo sparked public outrage when they put to death the healthy 18-month-old giraffe Marius. Here is why they killed him.

The scientific director of the Copenhagen Zoo is receiving death threats and has in recent days had his inbox filled with hate mail.

This is the result of a decision by the Copenhagen Zoo to take the life of an 18-months-old giraffe called Marius. After he was killed, technicians performed an autopsy for research purposes that was open to the public, and finally they fed the remains to the lions. The incident unleashed the wrath of local animal rights activists and dramatic headlines in international media.

But what exactly are the Zoo's arguments for putting down a young and healthy giraffe?

Culling is for the greater good of the giraffes

The man who pulled the trigger, the zoo's own veterinarian Mads Frost Bertelsen, says that a very positive situation lies behind the Zoo's action.

There was nothing wrong with Marius. It's just that others are better in a genetic perspective

”Up until now, we have not had to cull the giraffes. But now we have reached the point where the population is doing so well that a giraffe like Marius could not be relocated. Then the best solution is to put him down,” says Mads Frost Bertelsen.

The vet explains that a central European coordinator keeps track of pedigrees, and which genes are represented by individual giraffes in European zoos. The coordinator estimated from these data that Marius' genes were already well represented and recommended that Marius was killed to protect the population best suited to the gene pool.

“If Marius were placed in a different zoo, he would take the place of a better suited animal. There was nothing wrong with Marius as an animal. It's just that others are better in a genetic perspective,” says Mads Frost Bertelsen.

Marius' genes were well represented among giraffes in European zoos, and because of that he had to give way for a young giraffe with rarer genes.

The right time for Marius to die

Our function is not to keep the individual animal alive, but to keep the species alive

Marius was allowed to live for one and a half years, then that was it. At that age he can, according to Bertelsen, be described as a 'teenager'. It was an age when his father had also started roughing him up.

“In the wild he would leave the herd. If he were lucky, he would meet and join up with other young male giraffes. If he were unlucky, he would be killed by lions,” says Mads Frost Bertelsen, explaining that it was not unnatural for Marius to die young.

In fact, the young male giraffes are most at risk of being killed and eaten on the savannah, because they do not have the protection of the herd when they are looking for females to mate.

How to lead a natural life in the zoo

The Copenhagen Zoo lets the animals breed because one of the biggest challenges of keeping animals in captivity is that they are bored. They don't need to find or hunt for food, or fear enemies or diseases. Instead, a great activity for the captive animals is to find a partner, nest, have offspring, feed an raise their offspring, and finally spend energy on throwing the kids out.

“The side effect is that we have a surplus of animals. It is in fact fortunate that we can use them as food. Instead of killing 20 goats or a cow, we can use the giraffe,” says Mads Frost Bertelsen.

He points to the fact that in a zoo thousands of rats, mice, chickens, pigs, cows, etc. are killed every year to feed the captive carnivores.

Chief Zoologist Jens Sigsgaard from the Aalborg Zoo in northern Denmark says that there is nothing unusual about the Copenhagen Zoo killing a surplus giraffe. According to him this is done in all zoos - including the one in Aalborg.

“Our function is not to keep the individual animal alive, but to keep the species alive,” says the Jens Sigsgaard and continues:

“We have decided that even if an animal is over-represented in the gene pool, we will let it breed and have as normal a life as possible. We prefer to kill 'surplus animals' rather than send them to zoos we cannot approve.”

Sigsgaard explains that 'surplus animals' are already dead biologically speaking, in the sense that they do not contribute to the next generation.

The adult animals breed - the young must die

Aalborg Zoo has several arguments for allowing animals to breed, even if it may result in too many babies. As an example, Jens Sigsgaard mentions the Oryx Antelope:

“We have a herd of Oryx Antelopes that breed. Some of the calves are genetically inferior to others and will be less likely to get into the breeding program, but on occasion we have been able to relocate them to another zoo. It always depends on the current gene pool (the sum of the constantly changing antelope genes in zoos). Because of that, we let them breed, and when there are animals that cannot be placed somewhere else, they will be used as food,” says Jens Sigsgaard.

For the females it is also important to have offspring. Offspring that they - as in the wild - will have to part way with when they come of age.

“The animals are allowed to breed because it is an important part of their natural behavior to have offspring and experience the process of taking care of the them. Looking after the young is one of the best and most natural ways to occupy animals in captivity, In the wild there comes a time when the baby is old enough to break away from the mother and maybe become part of another group. That is the time when we try to find another well-suited zoo for it. If that is not possible, the young animal must be put down,” ” says Jens Sigsgaard.

The animals can also be adversely affected if they are not allowed to breed and have offspring. They may find it difficult ever to start breeding again. And if there are no kids in the flock, the younger animals will not get the experience of what it is like to care for babies.

Besides, contraceptives for animals such as p-rods (a contraceptive where a hormone stake is put under the skin) are not as well-tested and proven effective as in humans, and as a result the subsequent offspring can be born with birth defects.

The wild is rarely a way out

Another solution to deal eith 'surplus animals' could be to return them to the wild. This,however, rarely happens as it requires that at least four conditions are met:

- Resources - money and manpower must be available: Setting animals free is a big and expensive project.

- The right animal. The individual animal must be able to survive in the wild and far from all surplus animals are suited for it.

- Location. Zoologists need to find an appropriate place to let the animals out, and the local population must accept that it happens. This is not always possible. For example, people rarely want lions in the neighbourhood.

The Aalborg Zoo recently had to put down some surplus warthogs, but this did not cause a stir with the audience.

The reason why the killing of Marius the Giraffe caused such a public outcry may be that he looks more like a baby than for example a warthog.

Marius was cute - so humans want to protect him

Animal ethicist Jes Harfeld of the University of Aarhus says that animal offspring are perceived as cute because humans consider their own babies cute.

“Research has shown that traits like the large heads and eyes of babies trigger a certain nurturing gene with human adults,” says Jes Harfeld.

Baby animals often have similar features to human babies.

In other words a certain cuteness factor causes us to want to pet and take care of the baby animals.

“But it will typically apply to animals that are to some degree similar to us. People will probably not find a baby lizard particularly cute,” says Jes Harfeld.

So putting to death a baby lizard called Morris would presumably not have caused an emotional stir similar to the Marius case.

Translated by: Henning Høeg