Living power cables discovered in Danish bay

Scientists have found bacteria that function as live electric cables at the bottom of the sea.

About three years ago, researchers from Aarhus University made a strange discovery. They could measure electrical currents in the oxygen-free mud on the seabed of Aarhus Bay.

Remarkably, the scientists noticed that electrons were being transported from the oxygen-free mud a few centimetres below the seabed up to the oxygen-rich mud on the surface of the seabed.

Such a naturally controlled electron flow in saltwater isn’t supposed to be possible, so the discovery left the scientists with a great puzzle on their hands.

But now they have managed to solve the puzzle: it turns out that the electrons flow through hitherto unknown bacteria that are one centimetre long – a sort of live electric cable, which the scientists have dubbed ‘cable bacteria’.

“This is unheard of. Nobody has imagined the existence of organisms that function like electrical cables,” says microbiologist Lars Peter Nielsen, who is in charge of analysing the natural electrical currents.

“The bacteria can sit in the seabed in an oxygen-free environment and breathe as if there is oxygen. They just need to be connected to cells in the uppermost layer of the mud that still have access to oxygen.”

This sensational discovery is published in the scientific journal Nature.

One end breathes, the other eats

The cable bacteria are unique, since they are able to eat with one part of their body and breathe with another.

By passing one end of its body up through the mud layer, the cable bacterium manages to split up its breathing and its eating into two separate functions.

Using electron flow similar to that in electric wiring, the upper part of the cable bacterium can breathe the oxygen provided by the seawater at the uppermost millimetres of the seabed. Meanwhile, the lower part eats away at the sulphur compounds buried slightly further down in the mud.

”This gives the bacteria some unique opportunities that we’ve never seen before,” says Nielsen. “You could almost say that the cable bacteria breathe through a biological extension lead.”

Cut the cables and the current dies

The first thing the scientists did when they discovered the electrical currents three years ago was to examine the strange mud.

This is unheard of. Nobody has imagined the existence of organisms that function like electrical cables.

“When we pulled a thin wire across the mud, just like a cheese slicer, the current disappeared. It turned out that we had simply cut the cable. This revealed that the bacteria had some structure to it.”

Once they got the mud under their microscopes, they noticed a group of long, multi-cellular bacteria, which were present at all times when electrical currents were detected.

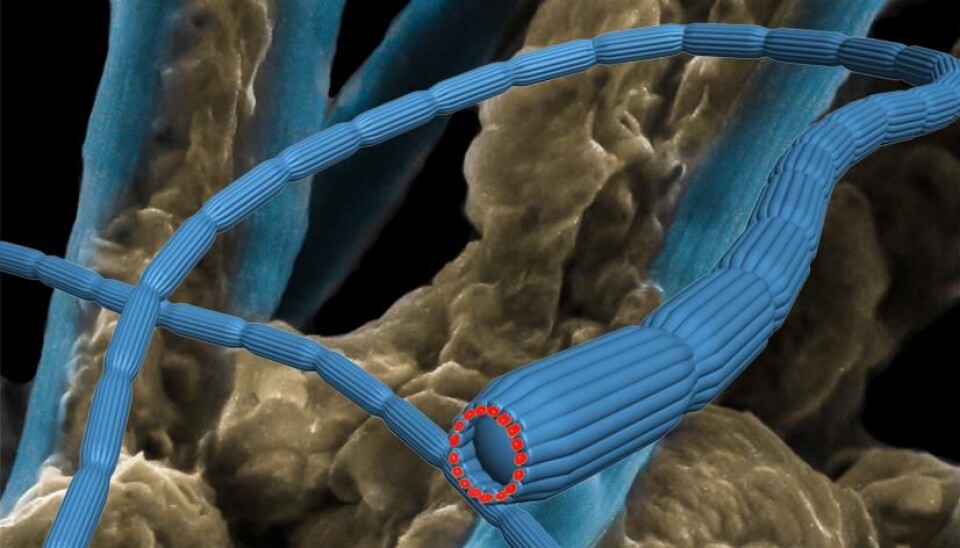

”The incredible idea that these bacteria functioned like electric cables really fell into place when, inside the bacteria, we saw wire-like strings enclosed by a membrane,” he explains.

Up to that point, the researchers had assumed that the current in the seabed ran between various bacteria through a joint external wiring network. So it came as a big surprise that it all actually took place within one long organism.

Kilometres of live cables

The bacteria can sit in the seabed in an oxygen-free environment and breathe as if there is oxygen. They just need to be connected to cells in the uppermost layer of the mud that still have access to oxygen.

The cable bacterium is a hundred times thinner than a human hair. It functions like an electrical cable with a series of insulated wires inside – similar to the electric cables we use on a daily basis.

”If you shake a lump of mud, you see that it’s full of these cables. There are typically ten thousand kilometres of cable bacteria in less than a square metre – so there are huge amounts of these bacteria.”

The researchers believe their discovery will add a new dimension to the understanding of interactions in nature and may find use in technology development.

----------------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther