Islands make large animals shrink and small animals grow

Mammals change size when they become isolated on islands. The phenomenon has been discussed for many years but is now confirmed by a new study.

Throughout Earth’s history, islands have been home to many strange species.

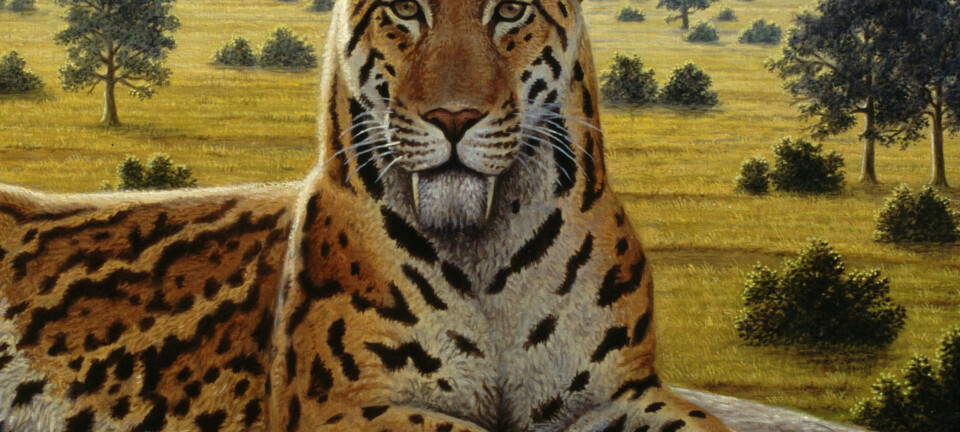

Take the Blunt-toothed Giant Hutia (Amblyrhiza Inundata), a type of guinea pig that was the size of a black bear, which lived on the Caribbean islands of Anguilla and Saint Martin.

Or dwarf elephants, which were just one metre high and became extinct some 1,000 years ago.

The phenomena is called the ‘island rule’ and describes the tendency of large mammals to shrink while smaller mammals become larger when isolated on an island.

The theory was first suggested 50 years ago and has since been fiercely debated by evolutionary biologists.

The island rule is real

Critics of the theory claim that it is a product of our own fantasy: a myth constructed out of our own tendency to see patterns even where there are none.

But now biologists from Aarhus University hope to put the argument to rest.

They have analysed the size of living and extinct mammals from the last 130,000 years when humans where expanding their own population around the world. Their analyses show that the island rule is not a myth.

The results are published in the journal The American Naturalist.

Man-made extinctions need to be included

One reason for the controversy is that previous studies failed to take into account the influence of man-made extinction events, says study lead-author Søren Faurby, a post doc from the Institute of Bioscience at Aarhus University, Denmark.

“The study shows that it can be difficult to understand the world if we don’t account for man-made extinctions. The island rule illustrates this--that our own influence on the environment affects our ability to understand evolutionary patterns,” says Faurby.

His colleague, Dennis Hansen agrees. Hansen studies island biology at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, but was not involved with the new research.

“For me the most important conclusion of the study is that we should never study evolutionary patterns without including extinct animals,” he says.

Not only that, we need to drop the idea that early man was naïve, primitive, and living at one with nature, he says.

“This was never true of islands. Whenever humans arrive on an island, a large part of the island’s fauna disappears very quickly,” says Hansen.

Should exclude bats

Many biologists include species like bats when studying the island rule, but this is a mistake, says Fauby.

Bats haven’t changed in size and so are often cited as evidence against the island rule. But by excluding them from the new analysis, Faurby saw that the island rule was applicable.

Hansen agrees that it does not make sense to include species like bats when studying the island rule.

“Bats aren’t isolated on islands in the same way as other non-flying mammals. And it’s the isolation of island ecosystems that makes the island rule possible,” says Hansen.

For him, any doubt about the existence of the island rule should now be laid to rest.

“Those people who think the opposite, need to have really strong arguments now. Especially because their scepticism is based on studies that count bats. But there are many good arguments for why bats shouldn’t be included in studies of the island rule,” he says.

------------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex