Inuit drum history longer than realised

Two 4,500 year-old pieces of frozen wood found in Greenland have added a couple of thousand years to the history of the Inuit drum. But they help little in revealing the drums’ origin.

Two deep-frozen settlements, Qeqertasussuk and Qajaa, were among the traces that some of the very first immigrants to western Greenland, 4,500 years ago, left behind at Disko Bay.

Unlike settlements elsewhere in the world, where only stone objects have survived thousands of years hidden in the soil, the deep-frozen remains in the Disko Bay area have also preserved perishable materials such as wood and bones, hair, feathers and skins.

Archaeological excavations at Qeqertasussuk and Qajaa in the 1980s brought countless otherwise unknown tools and objects to light – including harpoons and lances, tools with shafts, kitchen items, even parts of skin clothing.

Finds like this have gradually helped archaeologists draw a detailed picture of the people of the Saqqaq culture – the first inhabitants of western Greenland.

Now an extra dimension has been added because of the two pieces of frozen wood found among so many other wooden items from the two settlements that are now kept at museums in Nuuk and Qasigiannguit.

The soul of a culture

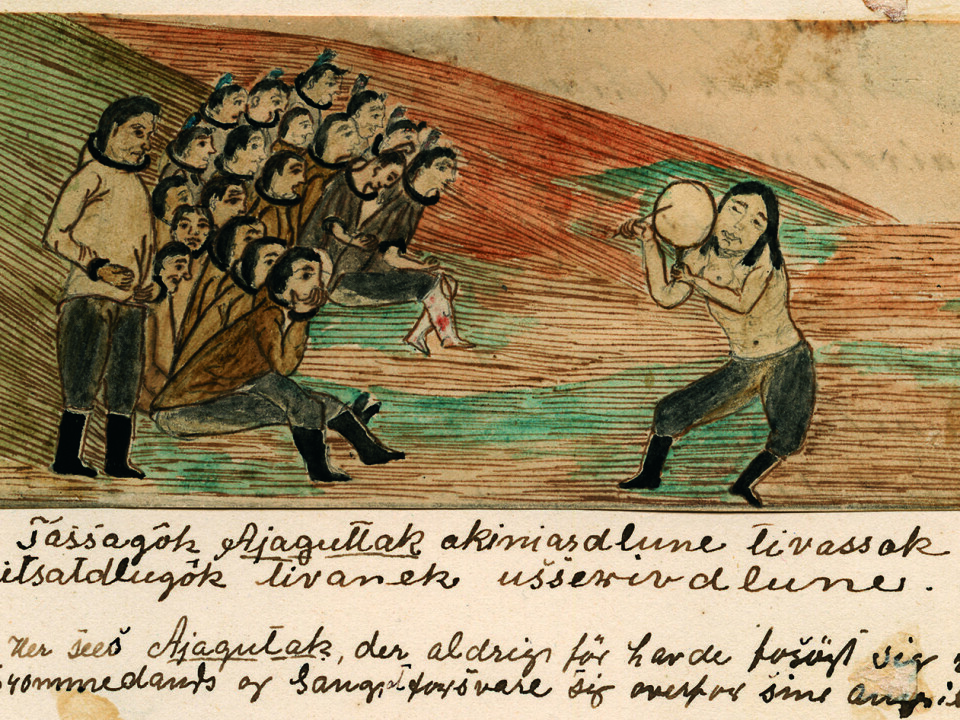

Archaeologists recognised the two pieces of frozen wood as parts of drums – used in drum songs and dances, which express the soul of the Inuit culture. Until Greenland was Christianised, the drum was the indispensable tool of the angakoq – the Inuit shaman – at séances.

Drum’s round shell

Several fragments from drum hoops were found at the two settlements, but two pieces of wood – one from each settlement – were particularly interesting.

They are bent strips 20-24 cm long, about 2 cm wide and 12-13 mm thick; both have a quite deep lengthwise groove.

Comparisons with other ethnographic objects show that wooden strips with this shape formed the round or oval hoop of a drum.

From other ancient drums we know that the drum’s hoop was often made up of several pieces of wood that were tied together, and the joint was perhaps reinforced by a tooth or a piece of bone.

The drumhead, of skin, would be stretched over the hoop and kept in place by a skin strap that runs in the groove and is tightened around the skin drumhead and hoop. The result is a flat drum, which the angakog would hold using a handle.

The piece of wood from Qeqertasussuk is made of spruce. Its ends are cut at an angle, and these surfaces have marks showing it was tied to other pieces of wood. This indicates that the Saqqaq drum hoop was made of several pieces.

Size and sound

What do these small pieces of wood tell us about the size of the Saqqaq drum?

As their curvature has been affected by the 4,500 years they spent in deep-frozen soil, we must instead compare their width and thickness with other ancient drums known from ethnographic studies.

Some of the drums that the Danish polar explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen collected from the Inuit in Canada during his Fifth Thule Expedition (1921-24) have a hoop that matches the Saqqaq drum in terms of height, thickness and cross-section.

This indicates that the drums from which the two pieces of deep-frozen wood from the settlements of Qeqertasussuk and Qajaa derived had a diameter of not less than 60-75 cm – rather larger than those known from Greenland’s history.

From a recent reconstruction carried out by Martin Appelt, an archaeologist at the National Museum of Denmark, in collaboration with the Greenland National Museum and Archives, we know that the drums gave a loud, deep sound when they were struck.

Adds years to the history of the Inuit drum

The discovery of drums belonging to the Saqqaq people must mean that the whole of the rich Inuit culture centring on drum songs and dances – and, perhaps, Shamanism – was brought to Greenland by the very first settlers, who came from Canada.

These Greenland drum fragments add several thousand years to the known history of Inuit drums. But tracing the first Inuit drums westwards is not easy.

Inuit came from Canada

The oldest preserved drum remains in Canada are about 1,000 years old and come from the Late Dorset culture. These remains are wood and derive from the hoops of three small, round drums about 25-30 cm in diameter.

The were found on Bylot Island in Nunavut, which comprises a major portion of northern Canada, and most of the Canadian Arctic archipelago, in the eastern Arctic area of the country.

A little piece of wood from the same time period, used for reinforcing a drum hoop, was found in Igloolik further to the southwest.

As all Inuit migration to Greenland took place from Canada, there is little doubt that the history of the drum is as long in Canada as it is in Greenland.

Even older in Alaska

Tracing the history of the Inuit drum is made difficult because wooden items have not been preserved at the many Canadian settlements from the Pre-Dorset culture, a Paleo-Eskimo culture that lived in the eastern Arctic from 2500 to 500 BC. This was contemporaneous with another Paleo-Eskimo culture, the Saqqaq culture, in southern Greenland, from around 2500 to around 800 BC.

Even further west, in Alaska, the first certain traces of drums are rather earlier than those in Canada – about 2,000 years old.

On St Lawrence Island, which lies in the Bering Strait between Alaska and Siberia, handles and hoops from drums have been excavated from permafrost layers at settlements from the Old Bering Sea culture.

No answers without wooden remains

All subsequent cultures in Alaska had drums, but the situation is similar to that in Canada: wooden objects have not been preserved in the oldest Alaskan settlements, which date from the Denbigh culture about 5,500 years ago.

This means we cannot prove that the first Inuit used drums – but the finds from Greenland make it very probable.

Nor can we trace the history of the Inuit drum back to Siberia – from where the first Inuit migrated eastwards over the new land bridge to Alaska that appeared in the Ice Age.

Only stone objects from this period have been found along the harsh coast of the Chukotka (or Chukchi) peninsula. But we can hope that future archaeological excavations find as well-preserved permafrost settlements in Siberia as those at Disko Bay.

The drum fragment found at Qeqertasussuk is already on display at the museum at Qasigiannguit, while the fragment from Qajaa is on display at the permanent exhibition of Greenland National Museum and Archives in Nuuk.

(This article is reproduced by kind permission of the Danish science periodical Skalk)

-------------------------------

Read this article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Michael de Laine

External links

- Greenland National Museum and Archives

- Bjarne Grønnow's profile on the National Museum of Denmark's website